Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Elgar – The New England Connection

Andrew Constantine / BBC NOW

Release Date: 6th October 2017

ORC100074

Symphonic Sketches – George Whitfield Chadwick

I) Jubilee – Allegro molto vivace

II) Noël – Andante con tenerezza

III) Hobgoblin. Scherzo capriccioso. Allegro vivace

IV) A Vagrom Ballet. Moderato. Alla Burla

Variations on an Original Theme ‘Enigma’ Op 36 – Edward Elgar

Theme. Andante

I) (C.A.E.). L’istesso tempo

II) (H.D.S-P.). Allegro

III) (R.B.T.). Allegretto

IV) (W.M.B.). Allegro di molto

V) (R.P.A.). Moderato

VI) (Ysobel). Andantino

VII) (Troyte). Presto

VIII)(W.N.). Allegretto

IX) (Nimrod). Adagio

X) (Dorabella). Intermezzo. Allegretto

XI) (G.R.S.). Allegro di molto

XII) (B.G.N.). Andante

XIII) (***) Romanza. Moderato

XIV) (E.D.U.). Finale. Allegro

History has a habit of leaving us a trail of leading lights and also cameo gures who played a significant part in the overall climate of their time but whose contribution is only fleetingly recognized. For every Mozart there must have been a hundred skilled, gifted and toiling composers successful in their time yet cast to the dusty shelves of music libraries around the world today. Is George Chadwick one of these? Does the genius of Elgar leave him in the shade completely or are there qualities in Chadwick’s works that we’ve overlooked?

George Chadwick and Edward Elgar lived almost parallel lives on opposite sides of the Atlantic. Born in rural Massachusetts in 1854, Chadwick was Elgar’s senior by three years. Elgar, born in Worcester in 1857, was to become everything Chadwick aspired to be yet wasn’t. Successful and respected as an academic, Chadwick was appointed director of Boston’s New England Conservatory (NEC) in 1897. Whilst he helped establish the NEC as a major international conservatory, it was recognition as a great composer that he sought most. In 1905 he wrote in his diary: “I dreamed of getting my newer compositions heard in Europe… I aimed at a possible work for one of the English Festivals”. Elgar, on the other hand, maintained a lifelong suspicion of academics and yet rose to become one of the most venerated composers of his era. As a self-taught maverick he maintained a haughty exterior and aloofness designed to garner recognition and also, perhaps, as a means of self-protection – a veneer covering his many insecurities.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century there is no doubt that Antonín Dvořák was the major figure in the musical life of America. Imported to add some Central European lustre and gravitas as head of the National Conservatory, Dvořák was an obvious figure to expand by example America’s own musical horizons. At the same time, in New England, an ambitious group of composers, the ‘Boston Six’ or ‘Second New England School’, was responsible for creating the first canon of America’s classical music. Whilst a number of them had furthered their studies in Europe – Paine, Chadwick, Whiting, Macdowell and Parker – they all held a strong admiration for the musical life of England. Indeed Horatio Parker’s oratorio, Hora Novissima, was the first work by an American composer to be performed at the prestigious Three Choirs Festival.

With the success in 1899 of his Enigma Variations, Edward Elgar suddenly emerged as the pre-eminent composer in the English-speaking world. From being a struggling, ‘jobbing’ musician (playing and teaching violin and gaining modest renown as a composer), Elgar became someone whose fame spread far beyond his home shores and both aspiring and practising American composers wanted to know more. By the time of the Enigma Variations, Chadwick had already composed three symphonies, his Symphonic Sketches and much more besides.

When Chadwick visited England in 1901 he was welcomed enthusiastically by London’s musical aristocracy, but was hugely disappointed not to make the acquaintance of Elgar himself; “He is the most serious composer the British have produced for many years”. Soon after this he tried to enter into correspondence with Elgar on several occasions. A postcard from Elgar, sent to Chadwick in early 1902, does little more than politely acknowledge Chadwick’s “very kind letter” and hope that he should one day have the pleasure of meeting him. Again, in 1904, Chadwick tried to further a “relationship” only to receive a similar polite but short response to his letter.

So, when did Elgar and Chadwick finally meet? Alice Elgar’s diaries have it

as early as July 3rd, 1905 when the Elgars were in Boston visiting after Edward received his Honorary Doctorate from Yale: “Drove to Conservatory and saw W. Chadwick who came on purpose…to see E.”

Yet there is no mention of this in Chadwick’s own diaries! What are we to make of this? It seems inconceivable that Chadwick would not have made the effort to meet such a rising star and surely Chadwick’s own friend Horatio Parker would have engineered just such an occasion? As Professor of Music at Yale, Parker was central to the whole Elgar celebration there, and indeed performed Pomp and Circumstance No 1 on the organ, which more than likely set up the tradition of playing it at all American graduations that continues to the present. They certainly did meet in London in 1906 when Chadwick was again in England trying to secure performances of his works: “Had a very jolly and interesting visit…, but I am not quite prepared to recognize him as the great genius that his cult would make him out”. Whatever the truth of the matter, Chadwick confessed around the same time to admiring Elgar’s technical gifts but not being totally convinced by his musical sincerity.

Whilst Chadwick’s star never rose as high as Elgar’s, his craftsmanship is readily apparent throughout his orchestral works. Like Elgar, he shows a compelling lyricism and the ease with which he writes for orchestra is superb. With his ability to conjure up images in music, painting pictures of everyday life, and with a sensitive response to literature and the world around him, there is little reason to doubt the claim that recognizes Chadwick as the first American nationalist composer.

In the Symphonic Sketches, George Chadwick prefaced each of the four movements with a short piece of verse, three by himself and one from Shakespeare, which describe well his musical intentions. Composed between 1895 and 1904 the sketches in many ways hark back to Chadwick’s time in Europe as a student and his adventures with the so-called ‘Duveneck Boys’ (a group of free-spirits led by the artist Frank Duveneck). Like Elgar’s variations, the composer uses his musical powers of description to conjure up images of either a character or impression of a situation. In Jubilee, individually the most frequently performed of the four, the joyous, celebratory and energetic character leaps from the page. The second movement, Noël, written in winter and named after his second son, had its origin, much like Elgar’s ‘Enigma’ theme, in a keyboard improvisation. In Chadwick’s case it was at the organ and was “made in church after ‘the long prayer’ ”. With the plaintive cor anglais solo at the heart of this movement, parallels between this and the slow movement of Dvořák’s New World Symphony are obvious. The third movement, Hobgoblin, was the last of the group to be composed and is a playful scherzo introduced by the French horn. The fact that movements 1, 2 and 4 were written a full eight years before the 3rd is curious. Whether Chadwick had always intended the Symphonic Sketches to be a four movement work is unclear – he may originally have intended a waltz to be placed there – but the fact that he came back to this, one of his favourite compositions, does indicate a desire to make it a more substantial whole.

The last and most descriptive of the four is A Vagrom Ballad. In this, Chadwick recreates the adventures and mishaps of vagrants living in the woods close to the railway tracks in Spring Field, Massachusetts. The movement is framed by an eerie, almost comical bass clarinet solo, whilst abrupt changes of tempo and musical direction give a slapstick flavour that is straight out of vaudeville.

“Your time of universal recognition will come”, said Nimrod, aka Augustus Jaeger, Elgar’s close friend, publisher and recipient of the most famous of the variations which have come down to us today as the Enigma Variations. Whilst not strictly its correct title, it is typical of the wily composer to use a cryptic name intending to add a degree of intrigue and help capture the public’s imagination. As the story goes, Elgar was relaxing at the piano with a cigar after a busy day of teaching when he started to form the simplest of themes that would become his starting point. The thirteen variations that followed represent his friends ‘pictured within’ – each indicated in the score by their initials – with the fourteenth, and grandest of all, being the composer himself, E.D.U., the pet-name his wife Alice would call him. That fame would finally come his way from an orchestral piece written in variation form should be of no surprise. Elgar had long been a master at composing ‘miniatures’ and a series of these was an ideal vehicle for his compositional style of the time, capable as he was of depicting perfectly either the character or mannerisms of the dedicatee.

Ultimately the self-confidence Elgar gained from the success of the Variations led to the later, more expansive orchestral works such as the two symphonies, the concertos for violin and cello and the symphonic poem Falstaff.

Andrew Constantine.

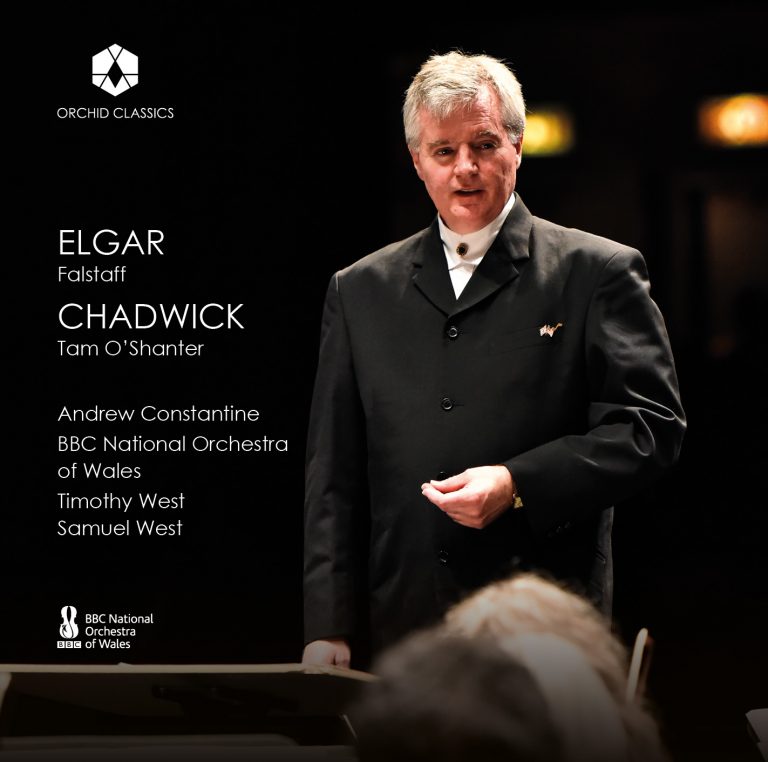

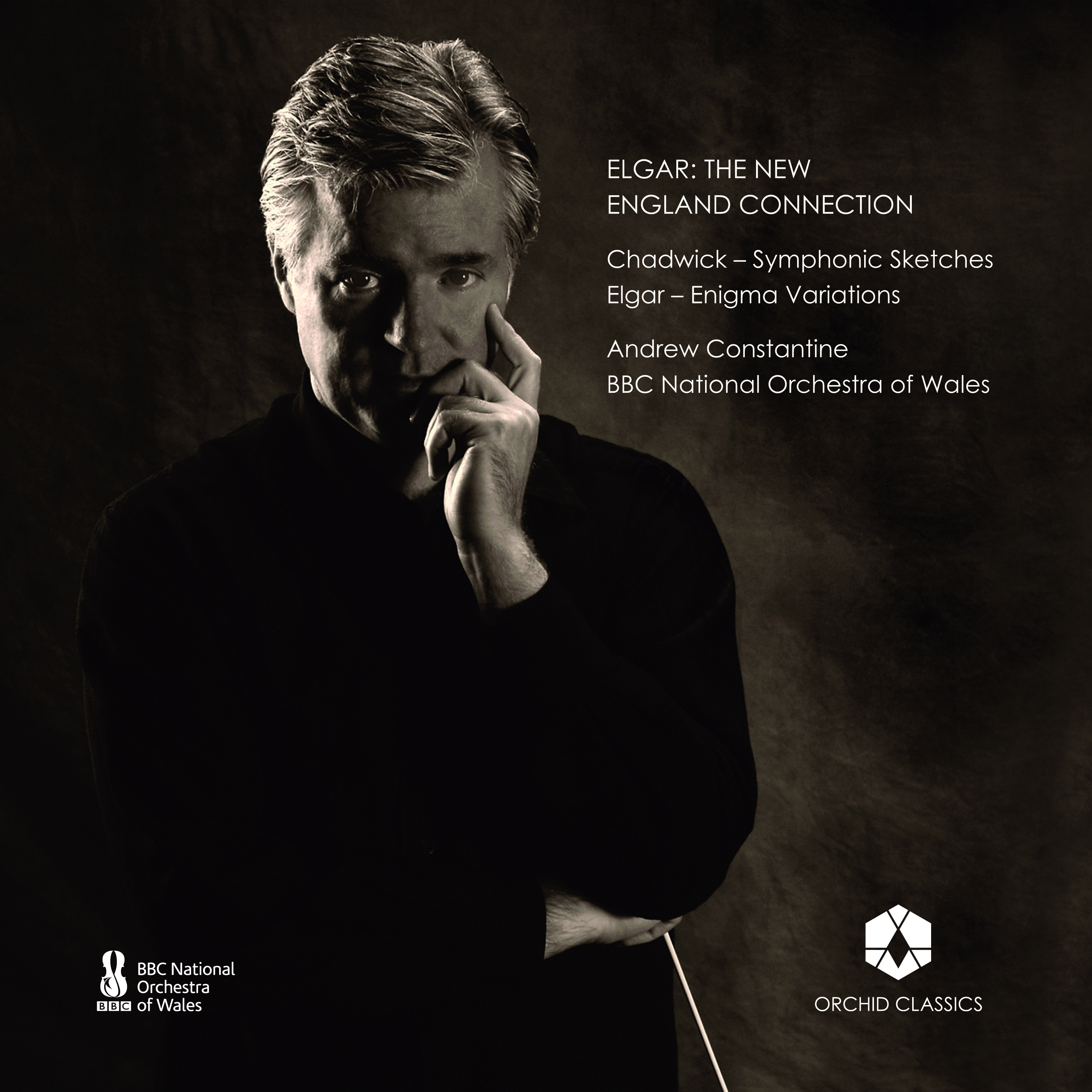

ANDREW CONSTANTINE

British conductor Andrew Constantine currently serves as music director of both the Fort Wayne Philharmonic Orchestra and Reading Symphony Orchestra in the United States, and was previously associate conductor of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. He began his conducting career in Leicester with the Bardi Orchestra and was later awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music degree by the University of Leicester for his ‘services to music.’ After winning the first Donatella Flick Conducting Competition he studied at the Leningrad State Conservatory with the legendary teacher Ilya Musin who described him as, a “brilliant representative of the conducting art”, and at the Academia Chigiana in Siena. Prior to his move to the US in 2004 he had already gained an enviable reputation as a conductor of great style and charisma, and also performed and recorded with most of the prestigious London orchestras including the Philharmonia, London Symphony and Royal Philharmonic. With a strong commitment to education and to bringing great music to as wide an audience as possible, Andrew Constantine has developed numerous creative and innovative programmes and was awarded a British NESTA Fellowship in recognition of his achievements.

BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE

….Splendidly imaginative and colourful….

….Constantine works up Nimrod to a point of satisfying high intensity….

GRAMOPHONE MAGAZINE

Let me urge immediate investigation of George Whitfield Chadwick….

Andrew Constantine leads a performance of winning affection and attentive spirit; he also secures a commendably spic-and-span response from the BBC NOW…..

…..Constantine himself pens a fascinating booklet essay…..