Artist Led, Creatively Driven

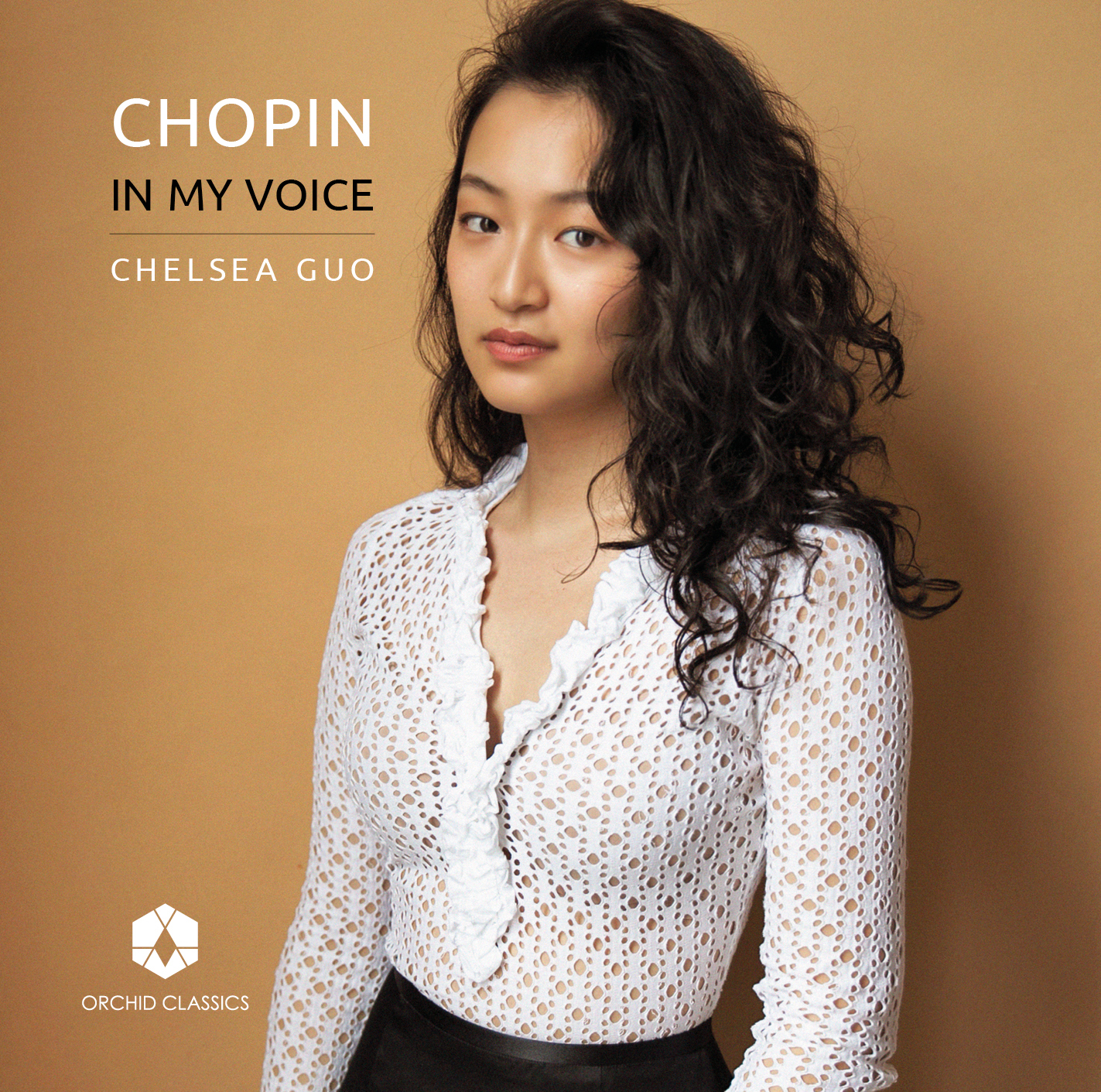

Chopin: In My Voice

Chelsea Guo, piano and voice

Release Date: 18th June

ORC100167

CHOPIN: IN MY VOICE

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Preludes, Op.28

1 Prelude No.1 in C major – Agitato

2 Prelude No.2 in A minor – Lento

3 Prelude No.3 in G major – Vivace

4 Prelude No.4 in E minor – Largo

5 Prelude No.5 in D major – Allegro molto

6 Prelude No.6 in B minor – Lento assai

7 Prelude No.7 in A major – Andantino

8 Prelude No.8 in F-sharp minor – Molto agitato

9 Prelude No.9 in E major – Largo

10 Prelude No.10 in C-sharp minor – Allegro molto

11 Prelude No.11 in B major – Vivace

12 Prelude No.12 in G-sharp minor – Presto

13 Prelude No.13 in F-sharp major – Lento

14 Prelude No.14 in E-flat minor – Allegro

15 Prelude No.15 in D-flat major – Sostenuto

16 Prelude No.16 in B-flat minor – Presto con fuoco

17 Prelude No.17 in A-flat major – Allegretto

18 Prelude No.18 in F minor – Allegro molto

19 Prelude No.19 in E-flat major – Vivace

20 Prelude No.20 in C minor – Largo

21 Prelude No.21 in B-flat major – Cantabile

22 Prelude No.22 in G minor – Molto agitato

23 Prelude No.23 in F major – Moderato

24 Prelude No.24 in D minor – Allegro appassionato

25 Fantasie in F minor, Op.49

26 Barcarolle in F-sharp major, Op.60

27 “Moja pieszczotka”, Op.74 No.12

Frédéric Chopin & Ernst Marischka

28 “In mir klingt ein Lied” (Étude, Op.10 No.3)

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

29 “Di piacer mi balza il cor” from La Gazza Ladra

Total time 73.24

Chelsea Guo, piano and voice

The vocal tracks on this album are both performed and self-accompanied by Chelsea, whilst also recorded simultaneously.

It is no secret that Chopin was mesmerised by the human voice, especially in the context of opera, but the mystery of why he never delved into writing for the genre still lingers today. Tad Schulc writes in his book, Chopin in Paris: The Times and Life of the Romantic Composer that Chopin was convinced that, “for him, the piano was the perfect instrument, capable of achieving everything that might be conveyed by one hundred voices on an opera stage”. Still, he called bel canto opera “the most perfect sounds in all creation”, deriving great inspiration from the intricate ornamentation employed by composers such as Rossini and Bellini, and expertly executed by leading singers of his time. Realising he could mimic, even exaggerate their abilities on his beloved instrument, he allowed bel canto to inform the way he imagined the notated improvisatory pianistic figures which became his signature compositional fingerprint. I chose to pair, alongside some of my most beloved piano works by Chopin, an art song written by him, an art song set to a melody composed by him, and a Rossini aria from La Gazza Ladra — the opera he spoke about the most in his letters — decorated in his improvisational style.

Chelsea Guo

Frédéric Chopin is one of those composers whose music is almost always unmistakeable; apart perhaps from John Field, there are few whose piano music combines complexity, delicacy and harmonic richness with such expressive power. Chopin’s biography continues to fascinate and divide opinion; journalist Moritz Weber recently suggested that translations of Chopin’s letters had been watered down by squeamish historians and that they reveal more passion for his male friends than for the women in his life. Others have countered that such expressions of affection were commonplace and not necessarily indicative of desire. The truth is still being sought out, especially in relation to the ways these parts of Chopin’s life may have been communicated through his music. As he wrote to the recipient of some his most intense letters, Titus Woyciechowski: “I now tell my piano things which I once used to tell you.” Chopin’s music has inspired passion, too. The Marquis de Custine wrote in 1848 that “people love each other, people understand each other in Chopin”.

Both Rossini and Chopin have drawn comparisons with Mozart: Rossini for his operatic style, Chopin for his prodigious ability. But it was J.S. Bach, another composer Chopin admired, who provided the model for several of his Études and for his Preludes. Chopin’s 24 Preludes, Op.28, composed between 1836 and 1839, do not precede anything (like the Fugues in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier), but are stand-alone pieces in every available key.

Robert Schumann dismissed Chopin’s Preludes as “sketches, beginnings of études, or, so to speak, ruins, individual eagle pinions, all disorder and wild confusions.” Even though he intended this as a criticism, Schumann articulated traits in the Preludes that have since come to be regarded as innovative rather than chaotic: their unpredictable, fragmentary, daring nature.

Chopin alternated Preludes in major keys with pieces in their relative minor, often leading to alternations in mood. The animated first Prelude in C seems sunny but has an unsettling undercurrent – and is over in a flash. The sombre second Prelude in A minor is full of melancholy chromaticism, and the Vivace G major Prelude is, like the first, almost skittishly quick, followed by the moving E minor Largo.

The D major Prelude, No.5, is a textural whirlpool, with major-minor jostling hinting at tensions beneath the busy surface; these are never fully explored and are instead peremptorily halted by a perfect cadence. In the B minor Prelude, the left hand is given the plangent melody accompanied by light chords. The A major Andantino and F-sharp minor Prelude reverse the pattern: the rapidity of the major-key Prelude is reserved for the F-sharp minor piece, whereas the A major Prelude is a haven of simplicity: an almost childlike melody accompanied by radiant chords. The longer molto agitato F-sharp minor Prelude lives up to its description but concludes with surprising gentleness.

Chopin exploits the piano’s deeper register in the majestic E major Prelude, No.9. The concise C-sharp minor Prelude is filled with cascades of notes and is followed by the equally brief but charming B major Prelude. In the G-sharp minor Prelude, the right hand’s chromatic ascents take the music in different harmonic directions, its apparently unremitting momentum eventually running out of puff.

The nostalgic F-sharp major Prelude, No.13, is contrasted with the harmonically dense E-flat minor Prelude, so brief it is almost Impressionistic, like a daub of dark paint. The lyrical D-flat major Prelude, known as the ‘Raindrop’, has outer sections of brittle delicacy, contrasted with funereal minor-key passages building to climactic chords.

The B-flat minor Prelude, No.16, opens with arresting chords before Chopin unleashes an inexorably virtuosic piece. The romantic A-flat major Prelude follows, and the metrically ambiguous F minor Prelude features elliptical phrases that are tersely interrupted by chords which eventually win the battle between these two types of material. The waltzing E-flat major Prelude seems more conventional but tapers off before setting off once again into some unusual harmonic regions. Resonant chords pervade the Prelude No.20 in C minor, creating a sombre atmosphere.

The cantabile B-flat major Prelude, No.21, is richly textured, with layers of spacious chords. The dramatic force of the G minor Prelude is juxtaposed with the light, witty penultimate Prelude in F. The set ends with the appassionato Prelude in D minor. There is no last-minute shift to the major; no happy ending, but a devastating and brilliant conclusion of three tolling Ds, deep in the bass of the piano. As Custine wrote to Chopin: “You have gained in suffering and poetry; the melancholy of your compositions penetrates still deeper into the heart”; but, even so, “… it is a consolation to be able to hear you sometimes; in the hard times that threaten, only art as you feel it will be able to unite men divided by the realities of life”.

In 1841 Chopin wrote: “Today I finished the Fantasy – and the sky beautiful, my heart sad – but that doesn’t matter at all. If it were, otherwise, my existence would perhaps be of no use to anyone. Let’s hide until death has passed.” He was writing of his Fantasie in F minor, Op.49, a piece which reflects this melancholy mood from its funereal opening march onwards. There are lighter moments, with major-key marching material and a lyrical central section, but even beneath these brighter veneers there remains tension, accentuated by a tussle between the two main tonal regions; and introspection, emphasised by the sombre chorale heard towards the piece’s end.

Chopin had been living in Paris and he was increasingly successful professionally, but his output between 1838 and 1841 was relatively sparse, and he devoted hours to studying counterpoint and re-evaluating his aesthetic. This bore fruit when he went back to Nohant, the residence of his partner, George Sand (the pen name of Aurore Dupont). On returning there in the summer of 1841, Chopin finished the A-flat Ballade, Op.47 and the Fantasy, of which pieces he wrote, “I cannot give them enough polish”, indicating the intensity of his perfectionism by this time.

Chopin’s Barcarolle in F-sharp minor Op.60 was written in 1845-46. The ‘barcarolle’ was a folk song sung by Venetian gondoliers, its 6/8 meter and lilting rhythm evoking the gondolier’s stroke. As with so many of the genres he tackled, Chopin took the barcarolle beyond its folk roots to produce something intricate and polished.

Chopin’s Polish songs were collected after his death and were posthumously published as his Op.74 in 1859. The twelfth, Moja pieszczotka (‘My Darling’ or ‘My Sweetheart’), dates from 1837, and is one of two Chopin settings of poetry by Adam Mickiewicz, a writer considered the national poet of Poland, Lithuania and Belarus and sometimes called “the Slavic bard”. The two verses of ‘My Darling’ contrast two facets of adoration: in the first, the poet expresses admiration for his beloved’s singing voice; in the second things become more visceral, with an ardent description of her features. Chopin responds with a voluptuous vocal line and waltzing accompaniment, building in passion during the latter part of the song.

Chopin began composing his 12 Études Op.10 in 1829 and worked on them in Warsaw and Vienna before completing the set in Paris in 1832. They are considered by many to be Chopin’s first masterpiece; as Robert Schumann put it: “imagination and technique share dominion side by side”. The critic Ludwig Rellstab did not share this opinion: “A player with crooked fingers will straighten them by playing these studies, but other players should be put on their guard against them”. In 1832 Chopin wrote to Ferdinand Hiller: “I write to you without knowing what my pen is scribbling because at this moment Liszt is playing my Études and transporting me outside my thoughts. I should like to steal from him the way to play my own Études.” They were published as the 12 Études à son ami Franz Liszt. The Étude in E major, No.3, is notable for its achingly tender melody. Liszt arranged some of Chopin’s songs for piano, but in this recording, we hear a sumptuous vocal version of this Étude arranged by Alois Melichar (1896-1976) to words by Ernst Marischka (1893-1963). The arrangement was made for Abschiedswalzer, a 1934 romantic film about Chopin himself.

Chopin was well acquainted with the music of Gioachino Rossini, and in a letter of 1825 mentioned that he had composed a Polonaise on a theme by Rossini who, meanwhile, referred to himself as a “pianist of the fourth class” and later wrote tongue-in-cheek homages to Chopin – among others – such as his Prélude prétentieux. Both composers achieved a great deal at a relatively young age. Rossini had cemented an international reputation by the age of 21 and in 1829, at the grand age of 37, retired a rich man, having composed 36 operas in 19 years. Of these, one of the most famous is La Gazza Ladra or The Thieving Magpie, first performed at La Scala, Milan, in 1817 and now best known for its overture. In the Act One aria ‘Di piacer mi balza il cor’, or Ninetta’s cavatina, the heroine introduces herself and sings of the joyful prospect of being reunited with her lover, Giannetto and her father, Fernando.

© Joanna Wyld, 2021

“Chelsea Guo is without a doubt one of the most talented musicians I know. She is a brilliant pianist as well as an enormously talented singer. Her accomplishments at such a young age are truly remarkable. I am grateful to have met and worked with this amazing young woman.”

– Barbara Bonney

A top prize-winner in the 2020 National Chopin Piano Competition, Chelsea Guo has earned praise for her “thoughtful performance” and as “a fine Chopin stylist” (South Florida Classical Review). She is currently pursuing a Bachelors of Music in piano at The Juilliard School under the tutelage of Hung-Kuan Chen and studying voice with Lorraine Nubar. Her solo piano and concerto performances have taken her to Carnegie Hall and Wigmore Hall as well as prominent venues throughout the United States, England, Austria, France, Poland, Italy, Germany, China, Japan, and Canada. In 2019, she was featured on WQXR’s “Young Artist Showcase” in a full hour of solo piano and vocal performance.

From an early age, Ms. Guo was drawn to singing. She has increasingly included vocal selections in her piano programmes, often displaying the influence that singers had on composers of their time. Having debuted as a pianist with the Tianjin Symphony Orchestra at age nine, Guo returned in 2018 as vocal soloist under the baton of Maestro Muhai Tang. She has been recognised for her vocal gifts as a 2019 National YoungArts Winner, the first prize winner in the 2019 Schmidt Voice Competition, and recipient of scholarships from the George London and Gerda Lissner foundations.

“When Chelsea plays the piano, I can hear the charming inner beauty of her singing voice behind it, deep, noble and shining. When she sings, I can sense in every phrase her harmoniously rich piano playing which I enjoy tremendously. The CD’s elegant and delightful programming combines it all and reveals Chelsea as a most fascinating and promising talent.”

– Arie Vardi

“It’s common for pop and cabaret singers to accompany themselves but it’s rare, to the point of being almost unique, to find such twin artistry in the more rarefied world of classical music. I was delighted to have Chelsea Guo share her extraordinary double talents with my WQXR Young Artists Showcase audience and am enormously gratified to greet the release of her substantial debut recording, evidence of her remarkable gifts as both pianist and vocalist. Here, clearly, is a major talent at work and a recording to cherish.”

– Robert Sherman