Artist Led, Creatively Driven

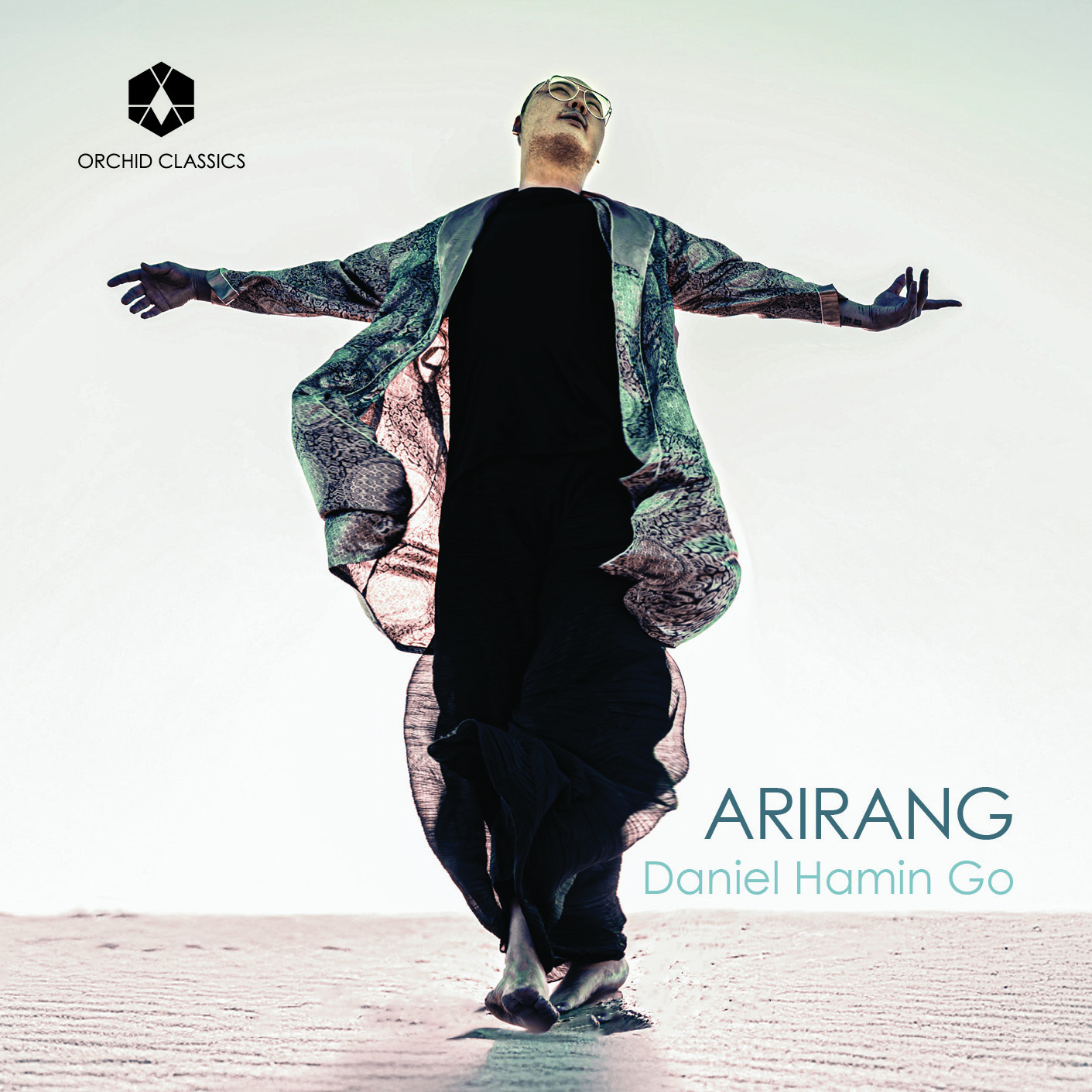

ARIRANG

Daniel Hamin Go

Release Date: September 26th 2025

ORC100397

ARIRANG

Marin Marais (1656-1728)

1. Suite in D Major, No. 63 – Les Voix Humaines

Caroline Shaw (b.1982)

2. In Manus Tuas

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959)

From Jewish Life, B.54

3. I Prayer

Anna Pidgorna (b.1985)

4. Grief Cycles – Variations on “Plyve Kacha Po Tysyni” for Cello & Piano

Ernest Bloch

From Jewish Life, B.54

5. II Supplication

Iman Habibi (b.1985)

6. Blood Moon

Ernest Bloch

From Jewish Life, B.54

7. III Jewish Song

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

8. Lob der Tränen, D.711

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Sonata for Cello & Piano, L. 135

9. I Prologue

10. II Sérénade

11. III Finale

Taran Plamondon (b.1995) & Daniel Hamin Go (b.1996)

12. Echoes of Arirang – Album Version

Daniel Hamin Go, cello

Benjamin Smith, piano

Jonathan Stuchbery, theorbo

The Gil Ensemble

Yemel Philharmonic Society

Arirang [ari – beautiful; rang – beloved one] is a representative Korean folk song that expresses a full range of human emotion—from delight and blessing to indignation and lament.

My debut album, ARIRANG, began as a personal journey through loss, reflection, and the search for meaning amidst grief. Surrounded by darkness, I found solace in the voices of composers who had transformed their own suffering into works of hope and beauty.

As the project unfolded, I realised that grief was not mine alone. The world was unraveling in pain—wars, injustice, and oppression echoed through every corner of the globe. It was then that ARIRANG became more than a personal expression; it became a response.

In 2023, I reached out to two friends: Anna Pidgorna, whose homeland of Ukraine remains in the grip of war; and Iman Habibi, whose work honours Mahsa Amini—a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman who died at the hands of Iranian police after being beaten for not wearing a hijab in Tehran, igniting the global “Women, Life, Freedom” movement.

Their voices, alongside works by Bloch, Debussy, Marais, Plamondon, Schubert, and Shaw, shape the soul of ARIRANG. Together, these pieces weave a path from darkness toward light—a testament to hope, resilience, and the unyielding human spirit.

ARIRANG brings together music from the last 600 years to explore ideas of humanity, conflict, loss prayer, reflection, hope and resilience. Individual works are paired or interleaved to create thoughtful connections as we listen. We begin with Marin Marais’s warmly evocative Les Voix Humaines for solo cello. Marais, the son of a Parisian shoemaker, found international fame as Europe’s leading viol virtuoso in the early 1700s and published almost 600 works for his instrument. These range from dance movements and character pieces to unusually descriptive or autobiographical music: memorials to his teachers, depictions of tolling bells, and even the intricacies of a medical operation. Here, the voices of human beings as Marais writes them – from pure fifths and octaves to jarring semitones and tritones – serve to remind us of the consonances and dissonances of human interaction. Daniel remarks that as far as he is concerned, we need more dissonance, not less – but find ways to approach the crunches with care and love, to find a route to resolution.

Marais’s voices fall silent with the arrival of Caroline Shaw’s In Manus Tuas, a relinquishing of control in the search for peace. Written in 2009, Shaw’s homage to the sixteenth-century British composer Thomas Tallis aims to ‘capture the sensation of a single moment’ of hearing Tallis’s motet In manus tuas in a church in Connecticut. The music spins and sings (as does the player), chords and rocking patterns ringing out across the strings with brief fragments of Tallis’s melody. ‘Into your hands, O Lord,’ reads Tallis’s text, ‘I commend my spirit.’

We move to another kind of prayer with the first movement of Ernest Bloch’s From Jewish Life, composed in 1924 when Bloch was working at the newly founded Cleveland Institute of Music.

This is one of a significant number of works in Bloch’s output that deal explicitly with matters of Jewish culture, worship and history, and which use Jewish musical modes as their basis. ‘Prayer’ is an impassioned, song-like movement tinged with darkness and hope – and at this point in the album, Daniel invites us to ‘travel back, and begin reflecting on our past and our grieving.’ It is followed here by the first of several new commissions, by the Ukrainian-Canadian composer Anna Pidgorna. Grief Cycles brings us to one of the current wars of the 2020s. It is a set of variations on a Ukrainian folksong which is now frequently played at the memorial of fallen soldiers. Pidgorna writes that for her and her countrymen, ‘this song contains all the grief not only of the last decade of war, but of centuries of horrific history of our land and people.’ She moves her theme through six different keys, the moods shifting according to an early nineteenth-century treatise on the emotional associations of different tonalities. The song itself, Plyve kacha po Tysyni (‘A Duckling swims in the Tisza’) is a conversation between a mother and her son, who is heading off to war. It is a tender, bleak, at times lullaby-like rumination on fear, violence and loss.

We return to Bloch for ‘Supplication’, its striking opening melody transformed and developed as the piece unfolds over shimmering piano chords throbbing bass rhythms. It is in part Bloch’s simplicity and directness that makes it so moving: his attempt to express his own personal conception of Jewish music.This is paired with another new work, Iman Habibi’s Blood Moon, which is both a supplication and memorial itself. Blood Moon pays tribute to Jina Mahsa Amini (1999-2022), who died at the hands of the Iranian police after being beaten for not wearing hijab in Tehran. A series of protests followed across Iran – the biggest in the country since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 – and the rallying cry of ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ also inspired solidarity marches around the globe. Blood Moon honours ‘the brave Iranian women who continue to strive for their basic human rights and societal freedoms’, as well as paying tribute to women across the world still fighting for their rights. Written using Persian tuning, the score contains several notes which don’t feature in a Western European classical scale, often presented as if the cellist is bending a note backwards and forwards within a circling passage. The music also seems to conjure the writing of J.S. Bach within its fluid, dramatic lines: music of mourning, prayer, rage and catharsis.

Following the brooding ‘Jewish Song’ – the last of Bloch’s three movements From Jewish Life and the most haunting and unsettling of the opus – we hear a song of a different kind. ‘If this doesn’t describe the definition of what hope really is,’ says Daniel, ‘I don’t know what does’. Schubert’s Lob der Tränen is a tribute to the healing power of tears, a sweetly lyrical, intimate Lied in which the poet August Wilhelm von Schlegel reflects that weeping reveals ‘the fields of heaven… every fierce passion is quelled… as flowers are revived / by the rain, / so do our weary spirits revive.’

With hope comes strength and resilience. Claude Debussy’s Cello Sonata is a work written by a man suffering deeply both from the depression of the outbreak of World War One, and exhausted from his struggle with the cancer that would kill him just a few years later. ‘I don’t know whether one should laugh or cry,’ Debussy wrote to a friend about his various musical projects in these straitened times. ‘Perhaps both?’ His Sonata is in three movements, beginning with a free-flowing, recitative-like Prologue. Debussy’s writing resounds with the delicate shapes, gestures and colours of Couperin and other French composers of the eighteenth century, whose music he so loved and admired. The Sérénade is uncertain and oddly clownish, the cellist plucking, bowing and sliding around the instrument. We move seamlessly into the Finale, in which Debussy demands fast, ‘light and nervous’ playing which is repeatedly stalled and the whole ends abruptly, the cellist taking control in a brief recitative that is followed by a series of brisk chords: a series of musical full stops.

The final piece is, as Daniel puts it, ‘a culmination, an ‘in hindsight’ musical offering that reflects, celebrates, and looks forward to what is possible.’ Echoes of Arirang is a celebration and commemoration of the 80th anniversary of Korean national liberation. ‘Arirang’ is a traditional Korean folksong, thought to be more than 600 years old and included in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list. It exists in thousands of variations and is constantly being reinterpreted and performed in new ways. The first section of Echoes of Arirang is based on a version of the song called ‘Holo Arirang’, or ‘Arirang Alone’, a pop tribute to the most well-known version of Arirang, written by HanDol (Heung-Gun Lee) in 1989. A minor-key interlude follows, conjuring the emotional concept of Han: anger, rage, grief and trauma. From this darker section we return to Holo Arirang but this time full of life and hope, which bursts through into the Korean national anthem, a moment of joy and solidarity. The final section features the most familiar version of the song today – but Daniel has made a small adjustment in the lyrics. The original looks forward to a time when people make it ‘over the Arirang hill’; but for Daniel we can no longer wait until we’re over the hill. ‘As people and as communities, we need to hold hands and work towards a brighter future.’

Daniel Hamin Go

Cello

The first time Daniel Hamin Go picked up the cello, he was 12. As he drew the bow across the open C string, the cello’s vibrations resonated throughout his entire body. He remembers being moved and filled with light – a light that has guided his desire to explore the truth that lies in life, in music, and in himself. It’s the light that fuels his need to connect with audiences and to share interpretations that demand a full commitment to emotional expression – and it’s what’s propelling his international career as a soloist and chamber musician.

Go has performed across three continents, making appearances at the Berliner Philharmonie, Cadogan Hall, Carnegie Hall, Flagey Studios, and Konzerthaus Berlin. A devoted chamber musician, Go has shared the stage with renowned artists such as Jonathan Biss, Glenn Dicterow, Miriam Fried, Ida Kavafian, Richard O’Neill, Daniel Phillips, Rachel Podger, Fazıl Say, and Jean-Claude Vanden Eynden. Go regularly performs at music festivals including the Four Seasons Chamber Music Festival, IMS Prussia Cove, Kronberg Academy, Krzyżowa Music, Music Academy of the West, Tsinandali Festival, and Yellow Barn.

Go is the founder of The Gil Foundation, with a mission of taking the everyday stories of pain, loss, and suffering, and transforming it into a work of art that serves as a testament to hope, resilience, and the unyielding human spirit.

Go performs on a cello made by Antonio & Rafaelle Gagliano, Naples ca. 1830, generously on loan by CANIMEX INC., from Drummondville (Quebec), Canada.

_______________________

Benjamin Smith

Piano

Described as a “thoughtful and immensely exciting performer” with “scintillating technique” (Barrie Examiner), pianist Benjamin Smith has performed as soloist and chamber musician across Canada, the United States, and Mexico. He has been a laureate of numerous competitions, including the Virginia Waring International Piano Competition and the CMC Stepping Stone Competition. Guest appearances include the Stony Brook Symphony Orchestra, the New Juilliard Ensemble, the Las Vegas Young Artists Orchestra, the Ontario Philharmonic, Orchestra London, the Burlington Symphony, and the Windsor Symphony.

Devoting considerable time to chamber music, Ben has been heard nationally on CBC Music, as well as radio broadcasts in the UK. He has partnered in recitals with a myriad of renowned artists, as well as with ensembles such as the Penderecki, Cecilia, Annex, and Tokai string quartets. For two seasons he performed as one-third of the Israelievitch-Smith-Ahn piano trio, and has recently been playing as a member of the Andromeda Trio. Festival performances include repeat appearances at Toronto Summer Music, Music Niagara, Festival del Lago (Mexico), and New Park (Ithaca, NY).

Dr. Smith currently serves on the faculties of both the Glenn Gould School (GGS) and the Taylor Young Artist Academy at the Royal Conservatory. His principal teachers have included Andrea Battista, James Anagnoson, Julian Martin, and Christina Dahl. Along with a DMA from Stony Brook University, he holds a Bachelors degree from the University of Toronto, an Artist Diploma from the GGS, and a Masters from Juilliard.

_______________________

Jonathan Stuchbery

Theorbo

Jonathan is a specialist in instruments of the lute and guitar family from Toronto, ON. A sought-after performer, he is praised for his “energizing precision” (The Whole Note) and “wistful lute performance” (La Scena Musicale).

He has performed with ensembles including Tafelmusik, Pacific Baroque Orchestra, Orchestre Baroque Arion, and in series across Canada like Festival Bach à Montréal, Early Music Alberta, and Musique Royale. Alongside soprano Sinéad White, Jonathan forms Duo Oriana, who released their debut album ‘How Like a Golden Dream’ in 2023. They have been featured by Early Music America, and overseas by the Lute Society (London), and St. George’s House, Windsor Castle.

He also engages in the creation of new repertoire for historical instruments. His own lute song ‘Initium Noctis’ is recorded on ‘How Like a Golden Dream’. Jonathan studied Early Music at the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya, and the University of McGill.

_______________________

Yemel Philharmonic Society of Toronto

Choir

The Yemel Philharmonic Society (YPS) is a non-profit organization founded in 1998 by Artistic Director Sung Soon Kim and a collective of Korean Canadian professional and amateur musicians. Based in the Greater Toronto Area, YPS is dedicated to inspiring, educating, enriching communities and promoting unity through the power of music.

Over the past twenty-seven years, YPS has earned a reputation for artistic excellence and innovative programming. Yemel presents a diverse repertoire spanning historical periods and musical genres, contributing meaningfully to the Canadian choral landscape. Yemel regularly supports emerging Korean Canadian musicians through its Young Artist Programs, and implements initiatives that enhance the well-being of community members across generations.

The name “Yemel,” meaning “Echoes of Art” in Korean, symbolises the choir’s role in amplifying cultural narratives, emotional expression, and artistic heritage within the Korean Canadian community. Through its enduring contributions to the arts, the Yemel Philharmonic Society is recognised as one of the finest artistic organisations and a vital cultural voice proudly representing the spirit, culture, and pride of Korean-Canadians.