Artist Led, Creatively Driven

ADAMS | BARBER | CONTE

Midsummer Light

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Michael Poll, conductor

Jack Liebeck, violin

Release Date: May 16th 2025

ORC100377

ADAMS | BARBER | CONTE

Byron Adams (b.1955)

1. Midsummer Music

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op.14

2. I Allegro moderato

3. II Andante

4. III Presto in moto perpetuo

David Conte (b.1955)

Sinfonietta for Classical Orchestra

5. I Overture

6. II Elegy

7. III Finale

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Michael Poll, conductor

Jack Liebeck, violin

Midsummer Light brings together three works that explore lyrical expression within American modernism. Rooted in a neo-romantic tradition that nonetheless embraces 20th‑century harmonic innovation, formal clarity, and lyricism, these pieces stand in deliberate opposition to the hyper‑rationalism of mid‑century serialism and the stark minimalism that followed. These composers cultivate rich tonal palettes, transparent orchestration, and emotional directness that assert a distinctly American voice.

Barber’s Violin Concerto (1939) exemplifies this confluence: it is anchored in a language reminiscent of that of Sibelius and Elgar and echoes the Brahmsian lyricism of earlier Americans including Arthur Foote (1853–1937) and George Whitefield Chadwick (1854–1931). The concerto’s harmonic surprises and rhythmic variety, however, give the piece a characteristic ‘New World’ feel. This blend of lush lyricism with dynamic harmonic and rhythmic language typifies Barber’s compositional idiom; Adams and Conte, writing later in the 20th and 21st centuries, extend this ethos in distinctly individual ways.

Byron’s Adams’s Midsummer Music unfolds in an arch‑like structure from a serene opening through an animated middle to a reflective close; Conte’s Sinfonietta traverses a Stravinskian opening sonata, a Copland-inspired elegiac central movement, and a vibrant, celebratory finale that recalls Poulenc’s harmonic world and hints at Conte’s formative years studying with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Though grounded in functional tonality, each work stretches its boundaries to trace a rich emotional arc.

“Summer afternoon — summer afternoon; to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language.” – Henry James

Byron Adams’s Midsummer Music is an impressionistic piece in a manner reminiscent of composers like Charles Tomlinson Griffes (1884-1920). Adams recalls that the initial impetus for his Midsummer Music for orchestra occurred in the mid-1980s when he first viewed ‘Summer’ (1890), by the American Impressionist Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851-1938).

The painting depicts four elegant, but indistinct, women clothed in diaphanous gowns dancing or floating (or both) to music provided by a seated woman with a golden harp. Later, Adams recalled this canvas while walking the Forest of Fontainebleau, noting the sun-dappled landscape to be similar to the lush green background of the Dewing; he sketched Midsummer Music between teaching and conducting duties at the American Conservatory of Music in Fontainebleau.

Midsummer Music contains an extensive quotation from Adams’s own art song, ‘Green’, a setting of a sensuous poem by D. H. Lawrence, as well as ‘Il était une bergère’, a chanson populaire that was first published in the seventeenth century, which recounts the naughty adventures of a young shepherdess, her cat, and a lascivious priest. Variations on this lively tune make up the work’s central section. After a return to the evocative music with which Midsummer Music began, the score concludes in a state of rapturous contemplation that gradually dissolves into silence.

Midsummer Music reached its final form in 1998, six years after the first sketches, and is dedicated to art historian and curator John Davis, who suggested that Adams seek out Dewing’s paintings.

Michael Poll

______________________________________

Of his Sinfonietta for Classical Orchestra, David Conte writes:

I have largely specialized in creating vocal music, choral music, and opera, but around 2009 I began to compose more instrumental music. Since that time, I have written a second string quartet, two piano trios, a sextet for clarinet, strings, and piano, sonatas for clarinet and French horn, and a suite for organ and brass quintet. Long study of the works of the composers I most admire has taught me that instrumental music is informed by a vocal impulse; I have therefore striven to imbue my Sinfonietta for Classical Orchestra with dramatic and lyrical melodies.

A sinfonietta implies a work shorter than the usual length of a symphony, and is often scored for smaller forces; mine resembles such concise scores as Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony and Copland’s Short Symphony.

Begun in June of 2012 and completed in October of that year, I scored the Sinfonietta for an orchestra of woodwinds in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. The piece is cast in three movements that are played without pause.

The first movement, ‘Overture’, is a spirited sonata form, quite classical in mood, with dotted rhythms reminiscent of a French overture and containing animated and steadily running sixteenth notes. The accumulation of rhythmic energy in the movement comes to an abrupt halt as woodwind solos are used to transition into the following movement, ‘Elegy’, This movement is filled with quiet intensity, as a ‘sighing’ motif in the strings is answered by florid woodwind solos. These two ideas are subtly developed and transformed, moving through various tonalities and culminating in several climaxes. The ‘Elegy’ concludes with woodwinds playing rising passages over a quiet roll on the timpani. The last movement, ‘Finale’, starts with vivacious figuration that arises from the depths of the orchestra, arriving at the announcement of a jaunty, syncopated theme proclaimed by the full ensemble. The elaboration of this theme proceeds to an animated climax that subsides into a second lyrical melody sung broadly by the violins. More development ensues, succeeded in turn by a protracted transition predicated on an ostinato. At this point, all of the themes heard throughout this movement are woven together in counterpoint; this passage leads to an energetic coda.

Sinfonietta for Classical Orchestra was commissioned by the Atlantic Classical Orchestra, Stewart Robertson, conductor, and was premiered on January 31, 2013. I later rescored the piece for eleven instruments: this version was premiered on 1 November 2016, with Michael Morgan conducting an ensemble comprising faculty members of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and players from the San Francisco Opera Orchestra.

______________________________________

When Samuel Barber started sketching his Violin Concerto in 1939, he had already enjoyed a string of successful performances. These included the 1938 premiere of his Adagio for strings, an orchestral arrangement of the slow movement of his String Quartet, Op.11 (1936), which was performed by the NBC Symphony conducted by Arturo Toscanini. This piece became his most famous work, earning a solid place in the orchestral repertory.

Barber hailed from an affluent and cultured family. He attended the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, which played a decisive role in his eventual fame. His distinguished teachers included Isabella Vengerova for piano, Emilio de Gonzorga for voice, and the composer Rosario Scalero. Scalero was a draconian reactionary both as a pedagogue and as a composer from whom Barber learnt vital technical skills while developing a habit of lacerating self-criticism. As a result, Barber often revised his music after a premiere.

Barber’s most popular compositions, including the Adagio and the Violin Concerto, display a warm lyricism derived from his preoccupation with creating vocal music. He composed many songs, including two song cycles, and two operas. With his suave baritone voice, Barber even recorded his own setting of Matthew Arnold’s poem ‘Dover Beach’ for baritone and string quartet, Op.3 (1931), in 1935.

During his time at Curtis, both as a student and later as a faculty member, Barber wrote several celebrated scores, including the Violin Concerto, Op.14. In 1939, a wealthy patron commissioned Barber to compose a violin concerto for his young protégé, the violinist Iso Briselli. Barber completed the first two movements by mid-October of that year, but Briselli found them insufficiently virtuosic. In response, Barber composed a perpetuum mobile finale reminiscent of the last movement of Ravel’s 1927 Violin Sonata. Briselli, however, was still dissatisfied. He demanded that Barber re-write the finale; Barber demurred and returned part of the commission fee. The concerto was eventually premiered on 7 February 1941 by violinist Albert Spaulding and the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy. The work was received enthusiastically by its first audiences. Some music critics, however, were dismissive: Virgil Thomson wrote cattily that the ‘only reason Barber gets away with such elementary musical methods is that his heart is pure.’ Barber himself was discontented with certain aspects of the initial score, and made several sets of revisions. As his biographer Howard Pollack writes, ‘Although Barber essentially finished the score in 1939, the premiere programme note gave its completion date as July 1940, indicating that the composer continued to work on the piece into the summer; considering, too, the additional changes made just prior to the premiere, the concerto alternatively might be dated 1940 or 1941, as opposed to the more customary 1939.’ In 1948, Barber made yet more improvements for a performance by violinist Ruth Posselt with the Boston Symphony conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. Barber’s Violin Concerto is now beloved by performers and listeners alike; it is one of few American-composed violin concertos to enter the standard repertory.

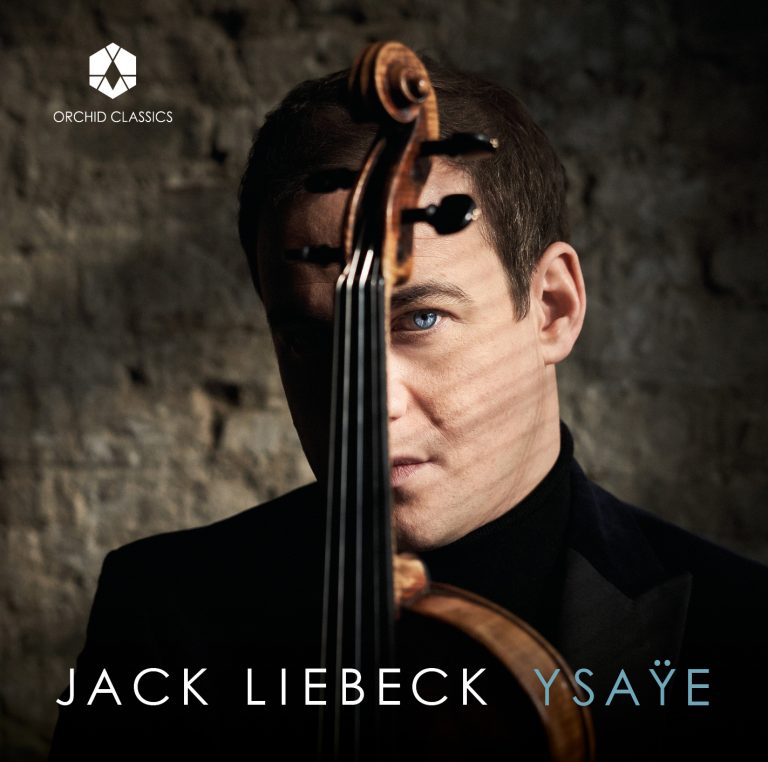

Jack Liebeck

Violin

In the 25 years since his debut with the Hallé, Jack Liebeck has worked with some of the world’s leading conductors including Andrew Litton, Leonard Slatkin, Karl-Heinz Steffens, Sir Mark Elder, Sakari Oramo, Vasily Petrenko, Sir Neville Marriner, Brett Dean, Daniel Harding, Jukka Pekka Saraste, David Robertson, Jakub Hrůša and major orchestras across the globe including Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Swedish Radio, Oslo Philharmonic, Belgian National, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony, Moscow State Symphony, Sinfónica de Galicia, Spokane Symphony, St Louis Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony as well as the majority of those of the United Kingdom.

Jack’s fascination with all things scientific culminated in the founding of his own festival in 2008 to combine Music, Science and Art, ‘Oxford May Music’. He has collaborated with physicist Professor Brian Cox in several unique symphonic science programmes which have included the world premieres of two violin concertos written especially for Jack: ‘Voyager Concerto’ by Dario Marianelli commissioned by the Queensland Symphony and Swedish Radio orchestras, and ‘A Brief History of Time’ by Paul Dean, commissioned by Melbourne Symphony. Jack gave the online premiere of Taylor Scott Davis’ new concerto for violin, choir & orchestra To Sing of Love: a Triptych with the VOCES8 Foundation Choir and Orchestra conducted by Barnaby Smith.

Jack is the Artistic Director of the Australian Festival of Chamber Music, the Émile Sauret Professor of Violin at the Royal Academy of Music, and a member of Salieca Piano Trio.

Jack plays the ‘Ex-Wilhelmj’ J.B. Guadagnini violin dated 1785, and the ‘Professor David Bennett’ Joseph Henry bow.

Michael Poll

Conductor

Michael Poll has performed in North America, South America, and Europe, including in Barbican Hall, Wigmore Hall, and the National Theatre of Panama. In 2023 Poll was appointed Associate Conductor of Central City Opera in Colorado; previously he conducted Bloomsbury Opera in London, leading new productions of Cosi and Figaro, during which time he also served as an intern assistant conductor to Franz Welser-Möst for Salome at the Salzburg Festival, and an observer to Barry Wordsworth for Copelia and to Sir Antonio Pappano for Meistersinger, The Ring, La Boheme, Madama Butterfly, and the Verdi Requiem all at the Royal Ballet and Opera. His debut guitar album, 7-String Bach, was called ‘masterful’ by Gramophone magazine, and Wholenote praised the ‘Warm, rich, and full tone’. Since its release by Orchid Classics in 2018, 7-String Bach has been streamed over 1 million times on Spotify and Apple Music.

From 2014 – 2018, Poll was Music Director of the Goodensemble Orchestra at Goodenough College in London, where he led a Gala in honour of Queen Elizabeth, a cycle of Beethoven piano concerti, and premiers by Sato Matsui, Joseph Stillwell, Igor Maia, and Raymond Yiu.

A 2010 Fulbright and a 2012 Marshall Scholar, Poll holds a BA in music summa cum laude from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in his Junior year, and was concurrently a visiting student at the Curtis Institute of Music. He also holds degrees from the Paderewski Academy of Music in Poland and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, where he was a Junior Fellow from 2015-2017, and was awarded a Doctorate in 2022 for applied aesthetics in musical arrangement. Poll has been a member of the faculty of the Bryn Mawr Conservatory of Music and the Polish Guitar Academy, a fellow of the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival, an advisor to the Southwark Music Service and is the Classical Music Programmer for Lancaster Arts. He has been active in the initiative SoundingLab, which brings live music into schools in the US and the UK, and is a 2024 recipient of the British Academy’s Small Project Funding. He is currently writing a chamber opera to a libretto by Sir David Pountney.