Artist Led, Creatively Driven

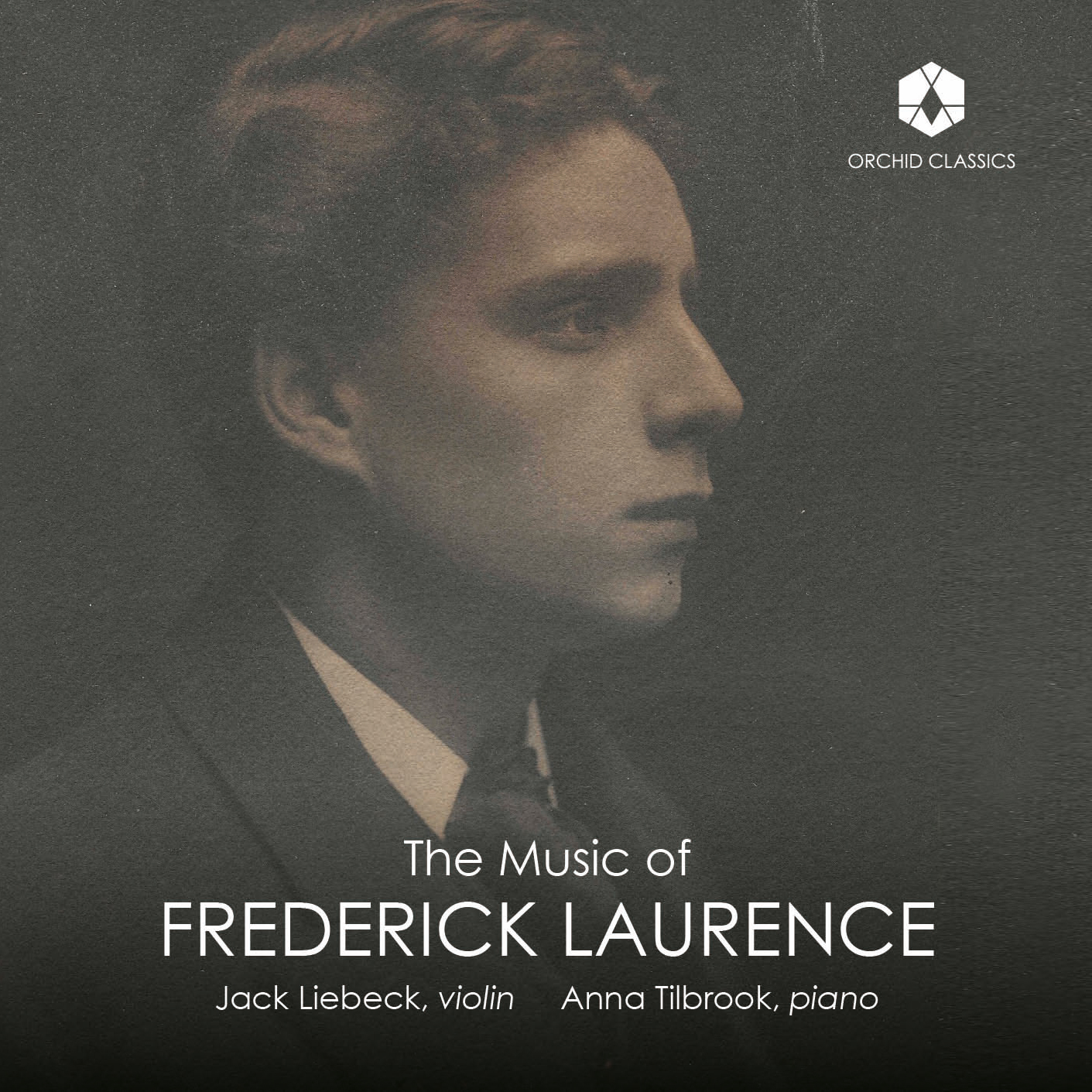

THE MUSIC OF FREDERICK LAURENCE

Jack Liebeck, violin

Anna Tilbrook, piano

Release Date: Apr 5th

ORC100284

THE MUSIC OF FREDERICK LAURENCE

Frederick Laurence (1884-1942)

1. SPRING NOCTURNE for violin and piano

CONTEMPLATION for piano

2. Allegro

ECSTASY for piano

3. Allegro

EROTIC for piano

4. Adagio

5. SONATA for violin and piano

INTERLUDES for piano, Op.11

6. Molto lento

7. Allegro

8. Largo

9. Moderato

PHASES for piano

10. Adagio

11. Larghetto

12. Allegretto

TRISTIS for piano

13. Adagio

Jack Liebeck, violin

Anna Tilbrook, piano

‘Lovers of good if difficult music would do well to obtain Frederick Kessler’s piano and piano and violin pieces. The works of this composer will go down in posterity’, declared The Cremona in January 1910. Though posterity hasn’t been as kind as then anticipated, with these first recordings we can now revisit this little-known composer.

Born on 25 May 1884 into a family of German heritage, British composer Frederick Kessler seemed almost intent on foiling attempts to follow his achievements by changing his surname by deed poll mid-career: in 1919 he became Frederick Laurence. (To avoid confusion, I will refer to him throughout as Frederick.) He was not alone at the time in undergoing this sort of nominal reinvention, being one of many who followed the British royal family’s mid-1917 lead of replacing German surnames with British ones in order to clarify their allegiances during and immediately following the Great War, when anti-German sentiment ran high.

Frederick’s musical career can be divided broadly into three phases. After receiving his earliest musical education from his father, in about 1903-04, as a 19–20-year-old, he became a private composition pupil of the still only 25–26-year-old Joseph Holbrooke, quite likely one of his first pupils. Holbrooke quickly became a keen promoter of ‘English music’, and from 1905 programmed the young Frederick’s compositions in his ‘Modern English Chamber Music’ evenings alongside his own works and those of other still young English composers such as Granville Bantock and Ernest Austin. Frederick clearly composed a great deal during these early years: a 1907 profile of the 23-year-old in a music journal lists 29 works with opus numbers, ranging from songs to solo piano works, to small chamber pieces (e.g. Piano Trio, String Quartet), to pieces for string orchestra or small orchestra, many with multiple movements. Most of these compositions can probably be considered juvenilia: they did not make it into print, are apparently substantially lost, and even Frederick later stopped listing them. His name change also immediately disconnected them from his later achievements.

Three early works that did make it to publication in 1907 under the name Frederick Kessler are included on this CD, and all three were reviewed at the time as ‘obviously unconventional and modern’. Though such a judgment was not always kindly meant, today we might wonder how compositions with such bold harmonic experimentation failed to attract more attention. The Interludes for Pianoforte, Op.11 (composed 1904; Sidney Riorden Publisher, 1907) is a collection of four short pieces reminiscent of late Hugo Wolf in interspersing an already expanded harmonic vocabulary with startling juxtapositions. Phases, Op.18 (Breitkopf and Härtel, 1907) plays around with chromaticism even more and is perhaps the most experimental of the works on this CD. The Three Studies for Pianoforte, Op.21 (composed September 1905; Sidney Riorden, 1907) explore more orchestral approaches to writing for piano and turn unconventional musical language to overtly descriptive ends with movements titled ‘Contemplation’, ‘Ecstasy’ and ‘Erotic’. Other works published at the time but not included here include Three Fantasies for Voice and Piano (composed 28 April 1906; Sidney Riorden, 1907) and Eucharistic Hymn (Opus Music, 1910). A Trio for Violin, Violoncello and Pianoforte, dated October 1912, was published in 1925 by Curwen.

About this time Frederick made the first of two remarkably well-aligned musical marriages. In 1909 he wed Mildrid Rebecca Hadfield, sister-in-law of his teacher Holbrooke. Some years after Mildrid’s 1921 death from cancer, Frederick went on (in 1926) to marry harpist Marie Goossens, a member of the Goossens musical dynasty. Though Frederick worked closely with other leading conductors of the day, formative professional opportunities were certainly allied with these family connections.

In 1916 Frederick started to work as librarian for music publisher Goodwin & Tabb, a role which provided him with a direct connection to the Queen’s Hall Promenade Concerts under Sir Henry Wood’s baton. There he eventually secured seven performances of his orchestral compositions, including two ambitious large-scale programmatic works: A Spirit’s Wayfaring (‘Poem for Orchestra’) under the earlier title Legend in 1918, and The Dance of the Witch Girl in 1920, which, according to an enthusiastic Musical Times, reflected all the ‘ultra-modern’ music that its composer had at his fingertips, and was very much liked by the public. Other large-scale works for orchestra (The Dream Harlequin, Milandor and A Miracle) were played as ‘rehearsals’ under the aegis of the Royal College of Music Patron’s Fund. Of these only the smaller-scale and contemplative Tristis, performed at five successive Proms (1919, 1920, 1921, 1922 and 1923) was published by his then employer Goodwin & Tabb in both string orchestra and organ arrangements. For this recording, Frederick’s great grandson Tommy Laurence has arranged the warm reflexivity of Tristis for piano.

While engaged with his high-profile Proms performances, Frederick was making arguably his most important contribution to the history of musical life in Britain, that is, to the film exhibition sector’s formative attempts to elevate the cultural standing of cinema with the help of quality musical accompaniments. From December 1921 to the end of April 1922 Frederick served as librarian and unsung behind-the-scenes score compiler for Eugene Goossens Jnr when the latter made his much-publicised appearance as conductor of a prestige film series at the Royal Opera House. Three years later he worked in a similar capacity with Eugene Goossens Snr for the musical accompaniment of London screenings of the high-profile expedition film The Epic of Everest (J.B. Noel, 1924). Now an experienced arranger of ‘special music’ for film using the most common technique of the day, that of ‘fitting’ a film largely using excerpts from existing music plus some newly composed segments, he next took on the job of composing an entirely original film score – the earliest important original score for a film screened in Britain: the Russian fairy tale film Morozko (1924). Overlapping with Morozko’s 1925 London run, Goossens Snr and Frederick shared musical credits for the opening night of London’s Film Society in October 1925: for that occasion, Frederick created a part-compiled score and was formally billed as Musical Director to Eugene Snr’s Conductor.

Given his position at the forefront of developments in taking film accompaniment seriously, had Frederick taken a different decision and stuck with moving pictures when the industry began the transition to synchronised sound film three years later, we might today have been celebrating Frederick Laurence as one of the founders of British film scoring alongside Arthur Bliss, William Walton, Ralph Vaughan Williams and the young Benjamin Britten. But instead of moving with this powerful new cultural form and capitalising on his own early involvement, Frederick concentrated on concert music, with diminishing success. The lovely Sonata for Violin and Piano on this recording was never published, and though undated was most likely composed during his period of peak exposure, between 1919 (when he changed his name) and about 1925, when the piece is referred to in a contemporary source. With occasional nods to post-Impressionistic harmonies, the sonata’s fluency of articulation sets it apart from the earlier piano works, now showcasing the composer’s confidence in writing expressively for violin, in a way that echoes his charming accompaniment to Morozko. The same intense feeling for the piano and violin pairing continues in Spring Nocturne (Curwen Edition, 1929); possibly inspired by home performances with harpist Marie, on the cover he writes ‘For Violin and Piano (or Harp)’.

In the 1930s, Frederick continued to compose, but notable public performances dwindled, and from 1932 much of his energy must have been consumed by his involvement in creating and then helping to manage a new ensemble under Sir Thomas Beecham that became known as the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Because Goodwin & Tabb had taken over Beecham’s music library from the Beecham Opera Company in 1919, the two men had already worked together. To start with, Frederick’s role consisted principally of selecting and managing the musicians, but by 1936, when there were three orchestral managers, his duties were the practical supervision and management of the orchestra and its music library. Unfortunately, upheavals in Europe and threats of war through 1938-39 led to LPO facing financial difficulties and subsequent liquidation. Though a small group of players re-formed the orchestra and ran it themselves, they did not re-appoint Frederick Laurence or Marie Goossens.

Such a career upheaval at age 55 must have been very difficult for Frederick, coinciding as it did with the onset of a second war. He tried but failed to secure work with the BBC, and turned to serving as a paid air raid warden. According to his wife Marie’s memoires, in 1941 he was invited to manage an orchestra that Sidney Beer was forming; however, Frederick died before being able to do so – on 3 May 1942, three weeks short of his 58th birthday.

© Julie Brown

Jack Liebeck

Violin

In the 25 years since his debut with the Hallé, Jack Liebeck has worked with some of the world’s leading conductors including Andrew Litton, Leonard Slatkin, Karl-Heinz Steffens, Sir Mark Elder, Sakari Oramo, Vasily Petrenko, Sir Neville Marriner, Brett Dean, Daniel Harding, Jukka Pekka Saraste, David Robertson, Jakub Hrůša and major orchestras across the globe including Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Swedish Radio, Oslo Philharmonic, Belgian National, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony, Moscow State Symphony, Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia, Spokane Symphony, St Louis Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony and most of the UK orchestras.

Jack’s fascination with all things scientific culminated in the founding of his own festival in 2008 to combine Music, Science and Art, Oxford May Music. He has collaborated with physicist Professor Brian Cox in several unique symphonic science programmes which have included the world premieres of two violin concertos written especially for Jack, Voyager Concerto by Dario Marianelli commissioned by the Queensland Symphony and Swedish Radio orchestras, and A Brief History of Time by Paul Dean, commissioned by Melbourne Symphony. Jack gave the online premiere of Taylor Scott Davis’ new concerto for violin, choir & orchestra To Sing of Love: a Triptych with the VOCES8 Foundation Choir and Orchestra conducted by Barnaby Smith.

Jack is the Artistic Director of the Australian Festival of Chamber Music from 2022, Émile Sauret Professor of Violin at the Royal Academy of Music and a member of Salieca Piano Trio. Also a professional photographer, he enjoys collaborating across many mediums and can be heard in the film soundtracks of The Theory of Everything, Jane Eyre and Anna Karenina.

Jack plays the ‘Ex-Wilhelmj’ J.B. Guadagnini violin dated 1785, and the ‘Professor David Bennett’ Joseph Henry bow.

Anna Tilbrook

Piano

Anna has been a regular artist at all the major concert halls and festivals since her debut at the Wigmore Hall in 1999 and frequently broadcasts on BBC Radio 3.

She has collaborated with many leading singers and instrumentalists including Lucy Crowe, James Gilchrist, Mary Bevan, Sophie Bevan, Barbara Hannigan, Sir John Tomlinson, Nicholas Daniel, Michael Collins, Natalie Clein, Philip Dukes, Jack Liebeck, Chloe Hanslip, Guy Johnston, Jess Gilliam and the Carducci, Sacconi, Elias, Navarra and Fitzwilliam string quartets. She has also accompanied José Carreras, Angela Gheorghiu and Bryn Terfel in televised concerts.

In 2022 Anna and James Gilchrist celebrated 25 years as a duo partnership. They have made a series of acclaimed recordings of English song for Linn and Chandos, the Schubert song cycles for Orchid, Schumann’s cycles, the songs and chamber music of Vaughan Williams with Philip Dukes and most recently “Solitude”, settings of Purcell, Schubert, Barber and a cycle written for James and Anna by Jonathan Dove, Under Alter’d Skies.

In August 2021 Lucy Crowe and Anna marked 20 years of working together by releasing their disc “Longing” featuring Lieder by Strauss, Berg and Schoenberg on the Linn label.

In 2023 Anna was on the jury for the Song Prize for Cardiff Singer of the World. She also teaches at the University of Oxford and Royal Academy of Music where she is an Associate.

If not sitting at the piano, Anna can normally be found watching cricket, playing tennis, having a gin and tonic or eating a curry!