Artist Led, Creatively Driven

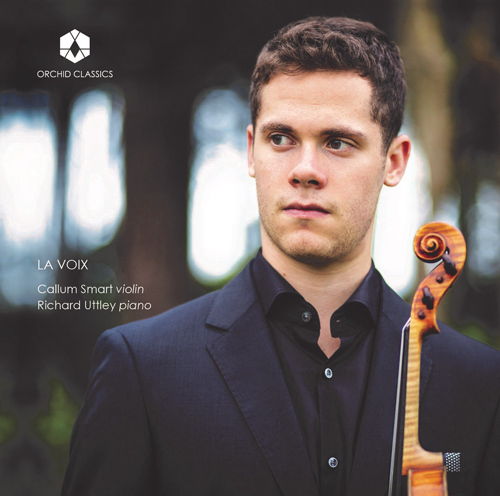

La Voix

Callum Smart, violin

Richard Uttley, piano

Release Date: 1st March 2016

ORC100053

Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963)

Sonata for violin and piano, Op.119

1 I Allegro con fuoco

2 II Intermezzo: Très lent et calme

3 III Presto tragico – Strictement la double plus lent

Gabriel Fauré (1845 – 1924)

Violin Sonata No.1 in A, Op.13

4 I Allegro molto

5 II Andante

6 III Allegro vivo

7 IV Allegro quasi presto

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

8 Tzigane, rhapsodie de concert

9 Pièce en forme de Habanera

Callum Smart violin

Richard Uttley piano

The starting point for the disc was French music for violin and piano, but a theme that emerged as we rehearsed and explored these works was that of the voice. As such, we decided ‘La Voix’ would make a fitting title. A vocal quality is central to all of this music, and each piece speaks or sings with its own particular type of voice. Poulenc’s Sonata has a distinctly Spanish accent, and at the same time as being a commentary on the tragedy of war, it demonstrates Poulenc’s feelings for one of Spain’s great literary talents, Federico García Lorca. The Fauré is nothing if not an extended love song, and a highly personal one at that – Fauré had hoped (in vain, alas) that it would help him woo Marianne Viardot, the sister of the work’s dedicatee. The two Ravel pieces, as with the Poulenc Sonata, are examples of a composer adopting the voice of another and in the process revealing something about themselves – the gypsy music of Tzigane and the sensual hispanic vocalise of the Pièce en forme de Habanera both a kind of tribute to the Basque-Spanish heritage of his mother, to whom Ravel felt so close.

Callum Smart & Richard Uttley

Francis Poulenc composed both his string sonatas, one for violin and one for cello, during World War Two. In the years approaching the War, he had written, “I don’t like this epoch, where one feels so rarely free”. He had attempted to write a violin sonata as far back as 1918, but with little success – not least because he did not particularly care for the sound of the solo violin. The dominant personality of the young violinist Ginette Neveu played a significant role in persuading Poulenc to make another attempt at composing the work.

Poulenc started work on the Sonata for violin and piano in 1942 and completed it in 1943; the piece was published in 1944. The first performance took place on 21 June 1943 in Paris, performed by Neveu with the composer at the piano. Poulenc was not entirely convinced by the piece, however, and argued that the only really idiomatic sections had been conceived by Neveu. Ginette Neveu’s life was tragically cut short by an aeroplane crash in 1949, when she was just 30 years old.

The angularity of the opening Allegro does suggest a composer wrestling to get to grips with the violin’s particular qualities, yet the results are refreshingly original. The abrupt opening gesture has been likened to a gunshot; a reflection, perhaps, of the war-torn environment in which Poulenc was living. The central Intermezzo, described by the composer as “vaguely Spanish”, conjures up guitar music with its strumming textures. “Vaguely Spanish” is far too modest, however; this is a movement of subtle, limpid beauty, with a delicious throwaway ending. The vigorous and taxing finale owes much to Stravinsky, whom Poulenc had adored since his youth.

The allusion to Spanish music relates to the work’s dedicatee, the Spanish poet and playwright, Federico García Lorca (1899-1936), who was killed by fascists in the Spanish Civil War. To dedicate his work to Lorca’s memory was a bold statement for Poulenc to make in wartime Paris. Poulenc felt a particular affinity with the writer, and would later compose Trois chansons de F. García Lorca in 1947.

Gabriel Fauré’s Violin Sonata was written against a backdrop of heartache. Fauré had been introduced by Saint-Saëns to the celebrated mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot in 1872, and soon fell in love with Viardot’s daughter, Marianne. He proceeded to woo her for four years; they became engaged, but the shy Marianne was overwhelmed by Fauré’s passion for her, and broke off the attachment in 1877. It was in the midst of this turbulent series of events that Fauré composed his first Violin Sonata, Op.13, in 1875-6. At this juncture, he was still hoping to be accepted by Marianne, and he dedicated the Sonata to her brother, violinist Paul Viardot. Perhaps inevitably, the emotional landscape of the piece reflects Fauré’s emotionally charged state to an unprecedented degree.

Fauré often spent his summers in Normandy with the engineer Camille Clerc and his wife, Marie. It was Camille Clerc who sent Fauré’s Violin Sonata to the publishing house of Breitkopf und Härtel in Leipzig; they agreed to print the piece, which, in 1877, became Fauré’s first published work, although he did not receive any royalties.

The Sonata was premiered on 27 January 1877 by the violinist Marie Tayau, with Fauré at the piano. The audience responded with great warmth, and Saint-Saëns declared that, “There is no stronger work among those which have appeared in France and Germany over the past several years,” adding, “and there is none with more charm.” Another composer, Florent Schmitt, stated that the appearance of Fauré’s Sonata “marks a red-letter day in the history of chamber music”. Certainly, one can hear characteristics which would prove hugely influential in the composition of later violin sonatas – Franck’s A major Sonata, written a decade later, in particular.

Into each movement Fauré weaves at least one theme of yearning beauty, with the violin and piano acting as equal protagonists. The first movement, in sonata form, brims with optimism and ardour, the two instruments sharing the full-blooded first theme. The brooding second movement is characterised by a distinctive pulsating rhythm which would recur in Fauré’s later works. There follows a chirpy Scherzo framing a lyrical Trio section, and a Schumannesque finale which combines tenderness with passionate drama.

Having promised the premiere of his Violin Sonata – planned for 1924 in London – to the Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Arányi, Maurice Ravel agonized over the work during the early part of that year. He then set it aside in March and concentrated instead on Tzigane, which, he told d’Arányi: “… I am writing specially for you, which will be dedicated to you and which will replace in the London programme the sonata which I have temporarily abandoned.”

Jelly d’Arányi was the great-niece of the legendary violinist Joseph Joachim, and was also Béla Bartók’s favourite interpreter of his violin music. Ravel had first met the violinist in Paris, in April 1922, when she played Bartók’s First Violin Sonata with the composer at the piano. Three months later, in London, Ravel met d’Arányi again; she gave a private performance of his Sonata for violin and cello with Hans Kindler, and then spent much of the night playing a seemingly endless array of Hungarian gypsy music for Ravel. It was on this occasion that Ravel first felt inspired to write Tzigane, a concert rhapsody which it would take another two years for him to complete.

The word ‘tzigane’ is a generic term for gypsy – referring more to style than race. In order to compose Tzigane, which is a sophisticated pastiche of gypsy music rather than an exploration of authentic tunes, Ravel requested specific models. He asked Lucien Garban at his publishers, Durand, to send him Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, and for another of his favourite violinists, Hélène Jourdan-Morhange, to bring him Paganini’s Twenty-Four Caprices. Ravel then combined the virtuosity and Hungarian flavour of his models to produce this dazzling display work.

Jourdan-Morhange sympathised with “poor Jelly d’Arányi” for having just two days in which to prepare Tzigane for the premiere, but also noted that the work was the only one in which she could hear “nothing of the essential Ravel”. Yet while the style may not be quintessentially Ravellian, what is characteristic is the way Ravel committed to this pastiche with such skill and daring. The slow ‘introduction’ for violin alone is as expansive as the musical fireworks, with piano, which follow.

At the premiere in Paris on 26 April 1924, the pianist Henri Gil-Marchex was persuaded to use a device called a luthéal, which made the piano sound like a cimbalom. The contraption, which soon became defunct, was adopted by Ravel to enhance the Hungarian quality of the music. The young Poulenc was informed by Henri Sauguet the day after the premiere that: “Tzigane is quite the most artificial thing Ravel has ever put his name to… a great success of course with the ladies with lorgnettes and the gentlemen with paunches.” However, such remarks do Ravel’s piece a disservice. The work is compelling, combining the violin’s acrobatics with real verve, harmonic flair and colouristic range.

Ravel wrote his Vocalise-Étude en forme de Habanera in 1907 to meet a commission for a collection of wordless songs aimed at students learning about the intricacies of modern vocal music. The music has become better known as the Pièce en forme de Habanera, arranged for numerous different instruments, including the violin, although not by the composer himself.

The piece proved to be a useful preparation for larger works such as L’Heure espagnole, although Ravel’s relationship with Spanish music went far deeper. His mother’s Basque-Spanish heritage remained a significant influence throughout his career, and undoubtedly shaped the composer’s enigmatic character. Until he was visibly moved by Wagner’s Tristan Prelude, Ravel had been a mystery to his friend Ricardo Viñes, who wrote that the composer “… seemed so cold and cynical… a most unfortunate and misunderstood person… He is, moreover, very complicated.” With rare candour, Ravel explained: “Look, they say I’m dry at heart. That’s wrong. And you know it. I am Basque. Basques feel things violently but they say little about it and only to a few.”

© Joanna Wyld, 2015

Callum Smart attracted wide public attention at the age of 13 having won the strings category of the 2010 BBC Young Musician Competition performing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales conducted by Vasily Petrenko and broadcast on BBC 2 and Radio 3.

Also in 2010, Callum became the top European prizewinner in the Menuhin Competition in Oslo. He has since appeared at a number of European festivals including the Dvořák Festival in Prague, the Menuhin Festival in Gstaad, Les Sommets Musicaux in Gstaad and the Valdres Sommersymfoni Festival with pianist Gordon Back, Mecklenburg Vorpommern with the Polish Chamber Orchestra and the Malmö International String Festival with Jonas Vitaud. UK recitals include Birmingham, the Cheltenham Festival, Glasgow, Leeds, the Lichfield Festival, Manchester, Newport and Perth. In March 2016 he gives recital performances with the pianist Richard Uttley in Birmingham, London’s Wigmore Hall, Konzerthaus Berlin and the Auditorium du Louvre in Paris.

January 2015 saw Callum make his Royal Festival Hall debut with the Philharmonia Orchestra performing Beethoven’s Triple Concerto under Michael Collins. Previous concerto appearances include venues such as Cadogan Hall and Queen Elizabeth Hall, London and performances with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales with Glazunov’s Concerto under Grant Llewellyn and Mozart Violin Concerto No.5 as part of a North Wales tour with Nicholas Collon, Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No.2 in Liverpool with Vasily Petrenko, Mozart’s Violin Concerto No.5 with the European Union Chamber Orchestra, and Britten’s Violin Concerto with the Chetham’s Symphony Orchestra at Lichfield and Cheltenham Festivals and the Bridgewater Hall, Manchester. In 2013 he performed Tchaikovsky’s Concerto with the Orchestra of Welsh National Opera and made his North American debut with the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Grant Llewellyn. In September 2016 he has been invited to perform Bruch’s Violin Concerto No.1 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Matthew Halls.

2014 saw Callum release his first recital album on Orchid Classics (ORC100040), which was met with critical acclaim. Described by Christopher Dingle from BBC Music Magazine as ‘an exuberantly assured debut’ the recording received four stars and was selected for special mention as June’s ‘The Strad Recommends’. He was also named as a BBC Music Magazine Rising Star: Great Artists of Tomorrow.

Callum began violin studies at the age of six and at nine became a student of Maciej Rakowski whose tutelage continued alongside his studies at Chetham’s School of Music. Currently in Indiana as the recipient of the Premier Young Artist Award from the Jacobs School of Music, he studies with Mauricio Fuks.

Callum plays on a c.1730-35 violin by Carlo Bergonzi.

About Richard Uttley

Richard has given solo recitals or played concertos in the UK’s major halls, and his playing has frequently been broadcast on BBC Radio 3. He has been recognised for his ‘musical intelligence and pristine facility’ (International Record Review), ‘amazing decisiveness … tumultuous performance’ (Ivan Hewett, The Daily Telegraph), and featured as a Rising Star in BBC Music Magazine.

He studied at Clare College, Cambridge, graduating with a Double First in Music, and with Martin Roscoe at the Guildhall School. His awards include first prizes in the Haverhill Sinfonia Soloist Competition and the British Contemporary Piano Competition, and he was selected for representation by Young Classical Artists Trust (YCAT) in 2011.

Recently, Richard has attended the International Musicians Seminar at Prussia Cove (Thomas Adès Masterclasses and Open Chamber Music), given regular recitals and made recordings with BBC New Generation Artist Mark Simpson (including Wigmore Hall and The Sage Gateshead live on Radio 3, and a film for Sky Arts), collaborated with visual artist Nat Urazmetova, and released his third solo disc Ghosts & Mirrors to critical acclaim.

Highlights of 2015/16 include Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time and the premiere of a new work by Rolf Hind at Cheltenham Festival; recording for NMC; commissioning and premiering works by Francisco Coll, Matthew Kaner and Naomi Pinnock; solo recitals in Bridgewater Hall and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival; and recitals with Callum Smart in Wigmore Hall, Konzerthaus Berlin and Auditorium du Louvre.

Richard is a trustee of New Dots, a charity promoting contemporary music.

“…in the hands of Callum Smart and Richard Uttley [Poulenc’s sonata’s] vocal quality is never in doubt … a rising star of the concert platform”.

– The Observer, 4*

“Smart’s sinewy, silky tone comes into its own in Tzigane, in which the long unaccompanied ‘improvisation’ sounds for once like an introspective meditation rather than the usual excuse for lashings of virtuoso fireworks”.

– The Strad

“Smart and pianist Richard Uttley are compelling advocates, capturing the impish humour and the underlying profundity … The long-breathed lyricism of Fauré’s First Sonata frequently finds Smart soaring majestically with Uttley rippling away incisively underneath.”.

– BBC Music Magazine, Double 4*

“[Smart] plays a dark, whimsical and biting bow … [Ravel’s Tzigane] is inspired, with a furious energy … a French programme, served with panache.”

– Artamag