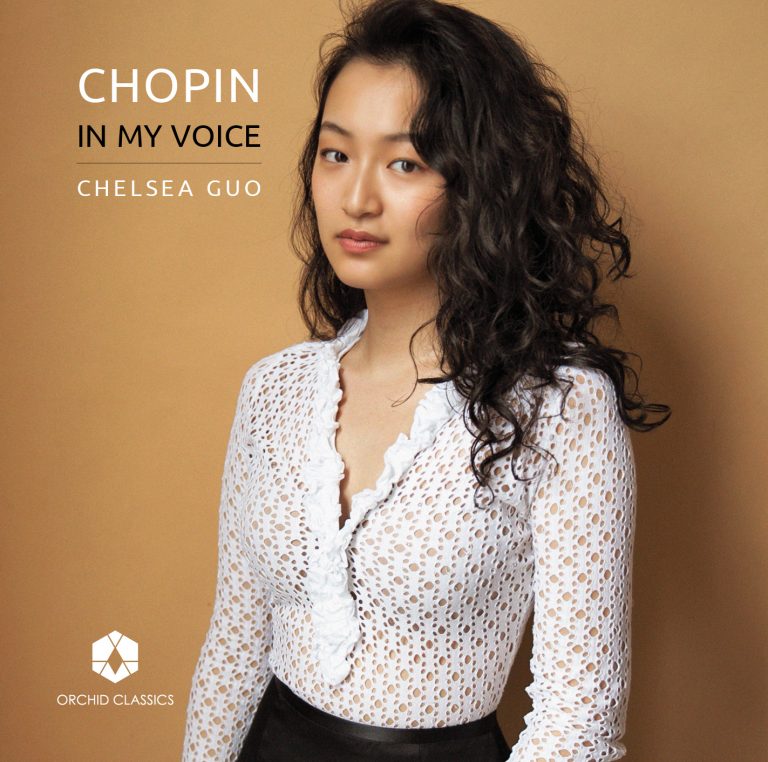

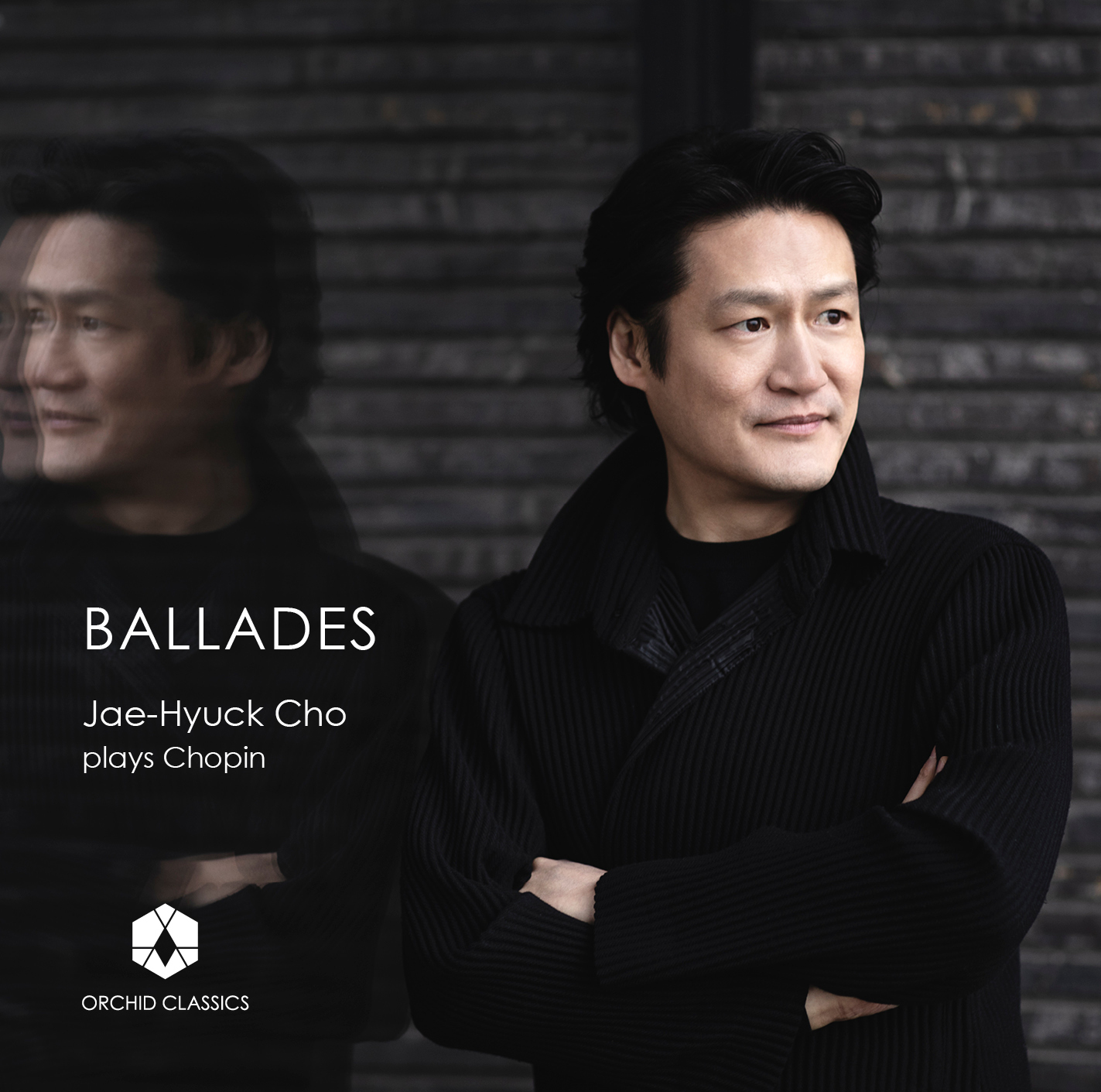

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Ballades

Jae-Hyuck Cho plays Chopin

Release Date: April 1st

ORC100193

BALLADES

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

1 Ballade No.1 in G minor, Op.23

2 Ballade No.2 in F major, Op.38

3 Ballade No.3 in A-flat major, Op.47

4 Ballade No.4 in F minor, Op.52

Piano Sonata No.3 in B minor, Op.58

5 I Allegro maestoso

6 II Scherzo: Molto vivace

7 III Largo

8 IV Presto non tanto

Jae-Hyuck Cho, piano

Chopin: The Poet of the Piano

Chopin is touted to be the ‘poet’ of the piano. One must wonder what that means. A poem is an art form of taking written words and arranging them so that language is elevated up to an artistic realm. I feel Chopin, then, was indeed a poet of the piano. He took the extant musical language of his time, expanded the musical vocabulary, and arranged them to make the expanded scope of expression possible. Chopin’s music requires a specialised kind of pianism: supple yet strong fingers, an almost infinite range of tone colours, a sense of timing that is well-proportioned but not exaggerated, etc. Nina Svetlanova was my teacher during my doctoral studies at the Manhattan School of Music. She entered Heinrich Neuhaus’s studio in Moscow when she was sixteen. In that studio, she learned of secret know-hows of piano playing. Playing legato (or mimicking as best as you could) was part of countless brilliant ways of playing the piano.

Because of the percussive nature of the instrument, the piano can never produce a true-legato line. Still, the goal is to make it as close to it as possible. It’s an illusion, but it creates a sense of wonder that overwhelms the listener when it works. Legato playing is essential in Chopin’s music. From Nina, I learned how to draw a better sonic line with particular ways of playing.

In this album, I dared to record Chopin’s Ballades and Sonata No.3. Performing is always a work in progress, for being a musician is a life-long quest. This album is a snapshot of where I was when the recording took place. I will understand and see more things in times to come; perhaps having these never-ending eureka moments about music is what keeps me going being a performer. Then again, musicians come and go through time, but music is forever. It’s magic.

© Jae-Hyuck Cho

The word ‘revolutionary’ tends to suggest a certain personality type: bold, larger-than-life, a natural leader. It is therefore too easy to forget that the delicate, sickly, rather unassuming Chopin was just that: a revolutionary. Chopin invented forms or made them his own; as Liszt argued, Chopin was perhaps less successful working with pre-existing forms but came into his own with those he pioneered – ballades, nocturnes, mazurkas, polonaises – because these were the forms that “suited his sentiment best”. The sonatas, preludes and études are examples of Chopin’s use of more conventional forms, but even here he injected something new into older models.

The four Ballades encapsulate Chopin’s originality. He coined the title and created the form, resulting in four single-movement piano pieces that are quite different in character, but share certain metrical and structural features and the Romantic spirit suggested by the title. The Ballade No.1 in G minor, Op.23 opens with an enigmatic, suspenseful introduction, after which unfolds a series of contrasting, often ardent episodes, their tempi stretched and pulled by Jae-Hyuck Cho to emphasise an almost demonic virtuosity as well as moments of full-throated passion.

It is uncertain when exactly Chopin composed the Ballade No.1; sketches date back to his stay in Vienna during 1831, and it has been suggested that when he was busy with teaching in Paris in 1835 he dug out the almost completed piece and polished it up. Yet its stylistic features have led to the alternative view that most of the Ballade was composed in 1834-35. It was certainly completed in 1835 in Paris and is dedicated to Baron Nathaniel von Stockhausen, Hanover’s ambassador to France. Robert Schumann declared that “my joy was great” when Chopin presented him with a copy, writing in 1836: “I have a new Ballade by Chopin. It seems to me to be the work closest to his genius (though not the most brilliant). I even told him that it is my favourite of all of all his works. After a long, reflective pause he told me emphatically: ‘I am glad, because I too like it the best, it is my dearest work.’”

Chopin began work on his Ballade No.2 in F major, Op.38 in 1836 while staying at the residence of his partner George Sand (pseudonym of Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin) in Nohant in central France. Two years later, Chopin, Sand and Sand’s children travelled to Valldemossa on Majorca in the hope of improving Chopin’s health. In January 1839 Chopin and Sand took delivery of a Pleyel piano there which, along with the emergence of Majorcan spring weather in the weeks that followed, enabled Chopin to work productively on a number of pieces. One of these was the Ballade in F major, which was completed by the end of 1839 and is dedicated to Robert Schumann. It is a piece of dramatic contrasts, ranging from the tender ‘sotto voce’ opening refrain – its sense of innocence emphasised in Jae-Hyuck Cho’s interpretation – to passages of fiery, ferocious virtuosity. Structurally the piece combines elements of both nocturne and étude, and its modulations are so extraordinary that Busoni thought it “badly composed”, balking at the wealth of forward-looking ideas.

Chopin’s output between 1838 and 1841 was relatively sparse, and he devoted hours to studying counterpoint and re-evaluating his aesthetic. Nohant continued to be an ideal retreat, however, and another of the works he completed there in the summer of 1841 was the Ballade No.3 in A-flat major, Op.47, dedicated to Pauline de Noailles. Chopin alluded to this and other scores written at this time as “cobwebs and manuscriptorial flies” and apologised for his music to his publisher, Fontana, explaining that “the weather is beautiful and my music horrible”. This self-criticism belies the joyful nature of the Ballade No.3, in which darker episodes only briefly cloud the prevailing sunshine. Jae-Hyuck Cho accentuates the work’s dynamic contrasts, bringing certain lines or gestures to the fore while others recede. Schumann hailed the piece as “most original”, and it was probably given its first public performance at a concert with the singer-composer Pauline Viardot at Pleyel’s salon in February 1842, an occasion described in La France musicale as “a charming soirée, a feast peopled with delicious smiles, delicate and pretty faces, small, shapely white hands; a magnificent occasion where simplicity was married to grace and elegance, and where good taste served as a pedestal to riches”.

In both the Ballade No.4 and the Sonata No.3, Jae-Hyuck Cho brings out the voice-like attributes of the melodic materials, like a singer expounding a lyrical line in the midst of more complex textures. Dedicated to the Baroness Charlotte de Rothschild, the Ballade No.4 in F minor, Op.52, dates from 1842 and is one of the pinnacles of Chopin’s output, brimming with poetic lyricism and subtle harmonies. He reached even giddier heights with the Piano Sonata No.3 in B minor, Op.58, written in 1842, revised in 1843 and dedicated to the Countess Émilie de Perthuis. The work was mostly composed during a happy stay at Nohant. George Sand wrote to the artist Delacroix that Chopin was working on “quite a little baggage of new compositions, saying, as usual that he cannot seem to write anything that isn’t detestable and miserable … the funniest thing is that he says this in perfectly good faith!”

The music critic Franz Brendel wrote in the journal founded by Schumann, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, that Chopin’s sonata was “one of the most significant publications of the present” – and it remains one of Chopin’s greatest achievements. In four movements, the work epitomises the Romantic spirit, with its exhilarating trajectory from a passionate opening movement to the brief Scherzo – much more emotionally wide-ranging than its ‘joke-like’ meaning would suggest – followed by a Largo that begins with an arresting statement before becoming hypnotically beautiful and song-like, and a turbulent finale that works its way towards a radiant coda in B major. The whole work is another instance of Chopin’s unique voice at its most articulate. As Liszt wrote in 1840: “… by now Chopin does not write anything which could as well come from another; he remains faithful to himself, and he has good reason for this”.

© Joanna Wyld, 2022

Jae-Hyuck Cho

Piano

Acclaimed pianist and organist Jae-Hyuck Cho is one of the most active concert artists in South Korea. He is one of the rare musicians who makes both piano and organ as his main instruments, he has been described as “a musician who is nearing perfection with extraordinary breadth of expression, flawless technique and composition, sensitivity and intelligence, insightful and detailed playing without exaggeration.”

Since making his debut at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall in 1993 as the winner of the Pro Piano New York Recital Series Auditions, Cho has been very active as a performing artist making appearances in various parts of the world. He has worked with numerous orchestras including Seoul Philharmonic and l’Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte- Carlo. In season 2020-21, Cho is making his UK debut as a recitalist and a soloist in Beethoven Festival of London, working with The Royal Philharmonic.

Cho’s discography includes his debut album of Beethoven Sonatas on SONY Classical where he released his second album of Beethoven and Liszt Piano Concertos No. 1 with Adrien Perruchon conducting the Royal Scottish National Orchestra that was featured in Gramophone’s ‘Listening Room’ shortly after its release. After a critically acclaimed release of his organ album recorded at la Madeleine, Paris under a French label Evidence, his latest collaboration with maestro Hans Graf and Russian National Orchestra of Rachmaninoff Piano Concertos No. 2 & 3 will be released on the same label later this year. His future projects include Mozart’s Piano Concertos with the Royal Philharmonic in London.

Born in ChunCheon, South Korea, Cho began piano studies at age five. He moved to New York to continue his piano studies at the Manhattan School of Music Pre-College Division with Solomon Mikowsky, and moved on to receive Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from The Juilliard School under the tutelage of Herbert Stessin and Jerome Lowenthal. He received the Doctor of Musical Arts degree from Manhattan School of Music, studying with Nina Svetlanova.

Cho started his organ studies at age sixteen at Manhattan School of Music Pre-College. He continued his organ studies while he was earning academic degrees majoring in piano. He served as organist/director of music in several churches in New York and New Jersey area for over 23 years. His last post was at The Old First Church of Newark, New Jersey, founded in 1666, where he had a privilege working with a professional choir and 100-rank Austin organ circa 1930s. His last major performances as an organist include a recital at St. Eustache of Paris, and at the Lotte Concert Hall of Seoul. Cho premiered Joseph Jongen’s Symphonie Concertante, Op. 81 at the Seoul Arts Center Concert Hall with Korean Symphony Orchestra.

Cho’s celebrated communication skills on stage opened doors for opportunities to expand his musical endeavors. He has been the guest artist in 252 episodes of ‘with Piano’, a special corner of ‘Family Music’ on KBS Classic FM Radio, creating the format of ‘Live Lecture Concert on Air’ where he shared commentaries and gave performances on a live radio broadcast. He has been the lecturer for Seoul Arts Center’s signature concert series ‘The 11o’clock Concert’, and continues to serve the roll as the communicator of music to the audience.