Artist Led, Creatively Driven

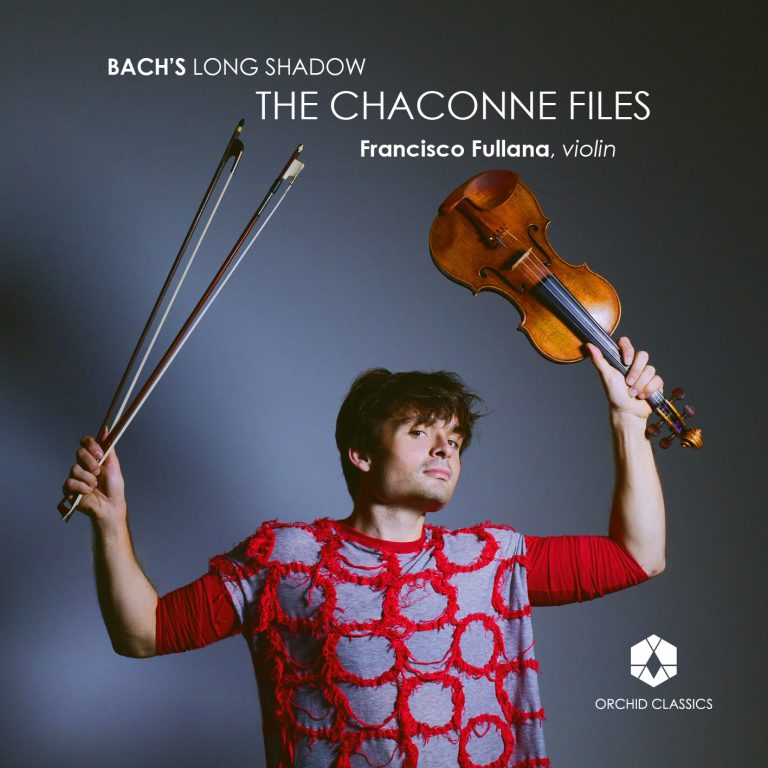

Bach’s Long Shadow

Francisco Fullana, violin

(special guest: Stella Chen, violin)

Release Date: 28th May

ORC100165

BACH’S LONG SHADOW

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931)

Sonata for Solo Violin, Op.27, No.2 “Jacques Thibaud”

1 Obsession

2 Malinconia

3 Danse des Ombres

4 Les Furies

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Partita No.3 in E major for Solo Violin, BWV 1006

5 Preludio

6 Loure

7 Gavotte en rondeau

8 Menuet I & II

9 Bourrée

10 Gigue

Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909)

arr. Patrick Loiseleur & Francisco Fullana

11 Asturias (Leyenda)

Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909)

arr. Ruggiero Ricci

12 Recuerdos de la Alhambra

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

13 Recitativo & Scherzo, Op.6

Encore:

Eugène Ysaÿe

Sonata for Two Violins

14 Poco lento, maestoso – Allegro fermo

Stella Chen & Francisco Fullana, violins

Total time 57.38

Francisco Fullana, violin

The entirety of solo violin repertoire stands on the shoulders of Johann Sebastian Bach, whose monumental Sonatas and Partitas redefine the violin as a polyphonic instrument. Bach’s Long Shadow explores the chain of influence and inspiration extending from Bach to other legendary artists over 300 years. The album opens with Eugène Ysaÿe’s metamorphosis of Bach’s E major Partita into an obsessive display of virtuosity, contrasted against the original Partita from the Leipzig master. The listener will then hear the polyphonous adaptations of the Spanish guitar classics Asturias and Recuerdos de la Alhambra, made possible only by Bach’s ground-breaking treatment of the violin as a polyphonic instrument. Next is Recitativo & Scherzo by Fritz Kreisler, a dedicatee and muse of Ysaÿe, performed on Miss Mary, the enchanting 1735 ex-Kreisler Guarneri del Gesù. My album juxtaposes baroque and modern bow, gut and steel strings, in its exploration of Bach’s solo violin legacy.

Francisco Fullana

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Partita No.3 in E major for Solo Violin, BWV 1006

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Partita in E Major, the last from his legendary set of six for solo violin, has been a part of my musical life since I was a boy just discovering that great body of work. To me, Bach’s music is the clearest representation of natural beauty created by man in the Western world. Each note functions as a drop of musical paint appearing in the space/time continuum. Each drop represents a precise intersection across centuries between Bach’s quill, the performer’s hands and the listener’s ears. Through the rapid succession of these musical moments, Bach is constructing a sonic cathedral that captures the beauty of the natural world in sound – even using devices that are ever present in nature such as the golden ratio which governs the arrangement of seeds within a flower. His music inspires not just complex feelings, like the music of other masters, but also resonates in a more powerful way: it fills us with an unadorned awe – a sense of wonder about what is beyond our reach, verging on mystical epiphany.

Bach’s music ignites the same questions I ponder when looking up into the depths of the night sky. Beneath starry nights, just like many people before me, I question the significance of human beings, myself among them, in the vastness of the universe. With Bach’s music, a similar question arises: what is my role – the performer – in the moments when I am playing this piece? Does the performance of his music generate an equal triangle between composer, performer and audience, or am I simply a middleman?

Maybe my search for the answer to this question goes back to the very beginning of my personal musical journey: What is more universal than the innocence and naïveté of a 9-year-old child? In Zen philosophy, the road to mindfulness is often compared to the state of mind that most children have. Maybe the right approach was the very first one. This E Major Partita’s opening Prelude was only the second Bach piece I ever learned, and the first one that I studied with my new teacher and mentor, Manuel Guillén. Earlier that year, my studying of Bach, specifically his A minor Violin Concerto, led me to work with Manuel, following a masterclass with Manuel’s former mentor, Vartan Manoogian, in my hometown of Palma de Mallorca. That put me on a path – the dream of coming to America, to Juilliard – which started with Bach himself.

Playing the Prelude’s famous opening still brings me back to those long hours of practicing with my dedicated mother beside me in the scorching heat of Villareal, just north of Valencia. Two weeks of intense work during my teacher’s summer programme led up to my first performance of this piece, in the gallery room on a hot summer evening. The audience was seated in darkness all around me, and I realised I was aware of the room’s square clay tiles. Of course, I was overdressed and sweating profusely, leaving Bach and me at the mercy of the bright spotlight. I remember my subjective experience of that youthful performance, but any memory of the music itself is long gone. Performing at that age felt like painting on a blank canvas, allowing Bach to supply the drops of musical paint on my canvas. The stage was the place where I just let go, where my self-judgement and inner dialogue floated away. This is an approach to performing that I still abide by today. In retrospect, that is where I became myself.

Fast forward now about a decade and a half, to the winter of 2013: I am in a maze of small cubicles that form the practice rooms at the University of Southern California. To most people, those rooms are claustrophobic, and the walls seemingly suck the soul out of you, an accurate description of what they do to your sound. But for me, my room was an oasis, where I could practice any time I wanted, explore the depths of my technique, the musical language of the great masters, and the new challenges that Midori, my teacher and mentor, brought up in every lesson.

It was in one of these rooms that I started questioning my whole approach to Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas. I had to change the way I listened to my own instrument, the way I felt the rhythm in my whole body. These are baroque dances after all! I needed a non-violinist expert to open my eyes to this new path and help me fully unlock the beauty in Bach’s music. I needed someone that wasn’t entangled in the numerous preconceptions and judgements that we violinists inherit through our education. It was through playing the third movement of the E Major Partita, Gavotte en Rondeau, for the baroque recorder specialist Rotem Gilbert that I came to discover the ethos of this piece. Through each one of its movements, a constant wave of optimism draws its energy from Bach’s utilisation of Baroque dance forms, breathing spirit into every note, in the way that the energy of the Sun brings life to Earth.

The Baroque dances, foundational to this Partita, were secular, rustic, energetic. The optimism and energy that the Partita exudes should be highlighted at every turn: on the downbeats of its Minuets, the fast runs of the Gigue and the speedy patterns of the Preludio. The excitement gets turned up on the repeats by the addition of ornaments: extra notes, turns and runs added in a spontaneous manner. In regard to the ornamentation, the performer’s role is clearly of a creator, hand in hand with Bach himself.

But how did Bach actually hear these pieces? I had been using our standard modern setup until this point in my life, playing on steel strings, with a bow that is much heavier than its baroque predecessor, and employing modern tuning. The standard “A” today is tuned at 440-442hz, much higher than the pitch used in Germany during Bach’s time. The actual pitch back in his era varied greatly from city to city. Musicians today consider 415hz as the generally accepted “A” pitch for German baroque playing. It is based on measurements of an 18th century tuning fork in Dresden’s Royal Chapel (measured prior to destruction of the building during the WW٢ bombing of the city).

Through the years and since that illuminating coaching session with Rotem, my exploration of baroque sound deepened. I added open natural gut strings to my instrument, started using a baroque bow, and experimented with ornamentation – these modifications all became tools to get closer to that ideal, to what Bach’s music must have sounded like during his time. These changes are important steps that contribute to the path I am choosing to take with Bach’s music: stripping my performances of his music down to what I believe is essential. Essence as a state of mind in which I am merely a medium for Bach’s musical definition of beauty to come through. In this space, I am fearless of any judgement, including my own, yet I only add my ideas to his music when, like with my ornaments, it is appropriate and complementary.

This path that I have decided to take with Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas is not without struggles and self-doubt. The deeper the exploration and the greater the acquired knowledge, the higher the risk of losing the meaning of the music itself. It is so easy to crowd one’s mind with historical context, with performance practice techniques and even personal experiences around the piece. The music can then become busy, no longer speaking for itself, as a performer overthinks and thus imposes too much on Bach’s sparsely notated manuscript. The process of stripping out anything superficial from Bach performance has to be a constant one – a battle that I fight every day in my own mind.

Fortunately, using gut strings and a baroque bow does facilitate the process of distilling the music down to the essential. The older technology isn’t designed to fill a cavernous modern concert hall with sound. Gut strings also require a higher level of focus and attention, as they aren’t as forgiving to excessive pressure or inadequate bow speed. One can’t overplay, or they will whistle or screech. They don’t allow for flashes of self-indulging flair; you just have to let the music happen.

During the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, it was Bach who kept me inspired. He kept challenging me, always causing me to return to one central question in my quest to bring Bach’s vivid representation of natural beauty to life: What is the role of the performer in these works? I wish I could ask that question to my 9-year-old self, because I feel he could answer in a way that no adult could. That natural innocence, that purity, gets lost along the way in all of us as we grow into adults. But I am also so grateful for the techniques, knowledge and life experience acquired through the past few years. That 9-year-old was not capable of asking himself the questions that I am grappling with. How could a child have known to embark on a search of what is essential in Bach’s music? He couldn’t even fully appreciate the natural beauty that surrounds us every waking moment. Or the incomprehensible beauty of the unknown, beyond this blue globe we call home. He didn’t even start to realise the value in Bach’s extraordinary capture of the beauty all around us.

So here I am, humbly presenting to you a snapshot – a moment frozen in time from my search for that essence that Bach so eloquently captured in his Sonatas and Partitas. The hope is that I am closer to stripping my performances of anything that could interfere with Bach’s notes. Letting his notes speak for themselves in that instantaneous intersection between him, myself and the listener. My goal, today, is to bring these new tools, this new understanding of the world, together with the pure, natural responsiveness of my 9-year-old self.

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931)

Sonata for Solo Violin, Op.27, No.2 “Jacques Thibaud”

Eugène Ysaÿe was the world’s leading violinist at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Belgium to a family of artisans in 1858, he became a brilliant violinist, true innovator, pedagogue, and composer. As a performer, he obsessed over his craft and the nature and range of his virtuosity. Pau Casals, the legendary Catalan cellist, said that Ysaÿe was the first violinist to “actually play in tune,” and Nathan Milstein called him the violin tsar. Listening to his recording of the Mendelssohn concerto from 1912, Ysaÿe at 54 years of age still has impeccable technique and clarity that any top violinist today would envy. He spent his later life composing in different genres, including concertos and chamber music, but he is most renowned for his six Sonatas for Solo Violin Op.27.

Ysaÿe was inspired to write the sonatas after attending Joseph Szigeti’s performance of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas. He himself admired the works from the Leipzig master, performing Bach’s monumental Chaconne often in recital. But the goal of his compositions was very different from Bach’s: Whereas Bach’s music challenges a performer to question whether any action or detail that one adds to his music is necessary, Ysaÿe’s compositions highlight his most acclaimed quality as a performer – remarkable virtuosity.

Following that goal, my focus when recording this piece was to carry my technique to the edge of what’s possible, in much the same manner as Ysaÿe pioneered in his playing over a century ago. That intensity, which sometimes veers into the obsessive, is a personality trait that I have carried throughout my life, making Ysaÿe’s 2nd Sonata a fitting opening to my first solo violin album.

Ysaÿe’s legacy as a composer is consistent with his focus on showcasing the technical skills of a violinist. His sonatas, written in his sixties, are each dedicated to six different leading violinists of that era, all younger, all friends whom he respected. All of the solo sonatas somehow reflect the style of each dedicatee, while also paying homage to the crown jewels of the solo violin repertoire – J.S. Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas.

His Second Sonata contains a central paradox. The sonata is dedicated – in its very title, which is rare – to Ysaÿe’s younger colleague, Jacques Thibaud, known for his colourful, expressive, and angelic sound. The sonata also borrows liberally from Bach’s E Major Partita, from literal quotations to repeated note patterns and chord progressions. At the same time, Ysaÿe confounds by structuring the entire sonata around the Dies Irae, the maniacal “day of wrath” section from the Mass for the Dead. This Dies Irae melody originated in the annals of the Catholic Church during the Middle Ages and was used by other composers such as Mozart, Brahms and Mahler as a symbol of death. The melody appears in all movements of Ysaÿe’s Sonata as an ongoing thread of devastation and anxiety.

By the time Ysaÿe finished his Sonata No.2 for Solo Violin in July 1923, he was an old man, and his frail health kept him away from the stage. The constant darkness in this sonata reflects both Ysaÿe’s obsession with Bach’s music and a desperation that may have come from the limitations imposed by his body.

At the same time, Ysaÿe managed to fit “inside jokes” into these works, and this sonata includes one of the most famous examples of his devilish wit. Thibaud was known for warming up with Bach’s E Major Prelude, while never wanting to perform it publicly due to the fear of having a memory lapse within the Prelude’s sea of notes. What better way to make light of Thibaud’s phobia and habit than by quoting directly from the Prelude, and using much of the structure, patterns and harmonies from Bach’s Prelude through the sonata’s whole first movement, titled Obsession? One can only speculate on why, with the exception of the Sarabande movement, Ysaÿe strayed so far from Thibaud’s best known qualities in his sonata. Was he issuing a challenge to his good friend, creating a kind of musical nightmare for Thibaud? Or were Ysaÿe’s frustrations with his own failing body pushing him into the realm of the sound world he created for this piece?

As a performer, I believe one must interpret this piece as the work of a madman, someone temporarily on the verge of losing his grip on reality. In the playing, I try to bring in dark fears and paranoia, to match the melodies that are ruptured by sudden outbursts of madness. Ysaÿe’s obsessive precision in his indications to the performer add to the troubled quality of the work: the nature of his markings stands in contrast to Bach’s sparse indications to the performer in his Sonatas and Partitas. Ysaÿe meticulously wrote in every fingering, bowing and expressive marking he could think of. He even created new symbols to indicate special techniques, such as the whole bow dash ( I—-I ). These new symbols are so numerous that they had to be explained in a full-page chart at the beginning of the score. With his writing, Ysaÿe was micromanaging the execution of every bar of the sonatas with an attention to detail that he must have followed himself when preparing for his concert tours.

Allow me to point the listener to the 2nd Sonata’s last movement’s title, Les Furies, the goddesses of vengeance in Roman mythology. Ysaÿe chooses to highlight the Dies Irae theme in the most maniacal way possible, with those persistent whole bow accents. The extreme virtuosity of the violinist is spinning out of control; the silences in between outbursts feel ever more violent with each iteration. In the quiet sections marked sul ponticello (on the bridge), the eerie and screeching sounds created with this extended technique cause one’s hair to stand up on the back of one’s neck.

Les Furies takes the violinist to the edge of a cliff, but in true Ysaÿe fashion, the music aims to achieve the clarity and technical mastery that the composer himself would have displayed had he played this sonata.

Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) & Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909)

Asturias & Recuerdos de la Alhambra

Isaac Albéniz and Francisco Tárrega are leading figures of Spanish Romanticism, a musical movement from the late 19th century inspired by traditional folk music across Spain. The sounds of the Spanish national instrument, the guitar, are ever present in both of these pieces, even in the arranged format for solo violin in this album.

In the case of Tárrega, the sound of the guitar is embedded in his identity, as he was the most celebrated guitarist of his time. He uses the constant whisper of tremolo technique, plucking the same note repeatedly on the guitar in rapid fashion, to create the illusion of a sustained note. And in Albéniz’s original version of Asturias, for piano, he employs the piano keys much as Tárrega called upon his guitar – with repeated notes at the top, melodies formed through the bass line, and harmonies in Phrygian mode drawn from the Flamenco tradition.

Both works transport the listener to a place of celebration and passion. They recreate an atmosphere that is common in any small village across the Iberian Peninsula during summer (other than in Covid-19 times). The music conjures images of a gathering of families and neighbours, a potluck meal, loud conversations and village gossip over cheap yet delicious local wine, with spontaneous performances breaking out once a guitar and maybe a cajón make an appearance.

Growing up in Spain, but having spent most of my adult life abroad, the music of Albéniz and Tárrega is at once familiar and foreign. On one hand, three of my grandparents are Andalusian, the birthplace of Flamenco: Granada on my father’s side for many generations, and Seville, where my maternal grandmother was born (in La Rinconada train station) and raised in a country ravaged by civil war. For me, the music resonates in a way that no other music does. It carries me back to my very first memory: holding my 92-year-old great grandmother’s hand at age two, walking around the block of her village home in Cacín, a farming village halfway between Granada and Málaga. The party lights shine inside the patio, and laughter and music escape the walls – this is my only memory of her.

On the other hand, it is also exotic, almost foreign: I have experienced these evenings more often through the movies, such as Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona, than in real life. My last visit to my grandparents’ Andalusian village was for my seventh birthday, and these are not the type of gatherings that commonly take place in a city – definitely not in the Madrid suburb where I spent my teenage years, let alone in NYC’s Upper West Side.

Performing these two pieces presents a dual challenge. The obvious one is the nature of the arrangements, trying to make the violin sound like a different instrument. They are full of technical obstacles such as the infamously difficult 3+1 off the string stroke, derived from Paganini’s invention in his fifth Caprice. A constant stream of three notes bouncing off the down bow and only one on the upbow. Ruggiero Ricci, the famous violinist who arranged these works, chose that technique as a successful and flashy way to imitate the guitar sound in Tárrega’s music. Asturias’ pianistic writing is its biggest technical obstacle. The awkward chords in the middle section were written to be played on a piano, an instrument where intonation and string crossings aren’t an issue.

But there is also the mental challenge – recreating an atmosphere for which I have few reference points in real life. I try to let my instincts take over, allowing the Spanish blood from my ancestors to flow through my fingertips and carry me back to my Andalusian roots.

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

Recitativo & Scherzo, Op.6

Fritz Kreisler is one of the giants of the violin world. The life-loving, sweet-sounding legendary violinist left a legacy of musical delicacies, including his most famous work for solo violin, Recitativo & Scherzo, Op.6. Born in Vienna in 1875 to Sigmund Freud’s family physician, Kreisler was a child prodigy, even touring the US at age thirteen, when he debuted with the Boston Symphony. I can’t think of a better description of Kreisler, both as a composer and performer, than the picture painted by violinist Carl Flesch: “Kreisler’s cantilena was an unrestrained orgy of sinfully seductive sounds, depravedly fascinating, whose sole driving force appeared to be a sensuality intensified to the point of frenzy.”

Recitativo & Scherzo meets at the crossroads of this project on multiple levels. Written in 1911, it was dedicated to Eugène Ysaÿe, who had been a fan of Kreisler since attending his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1898. One of his few works numbered with an opus number, signalling his pride for the composition, it features two contrasting movements: a dark opening Recitativo full of gusto, followed by a waltz-like Scherzo in ¾ meter that transports the listener to the ballrooms of pre-war Vienna.

Then there is the direct connection between Kreisler and me: the instrument I am fortunate enough to call my musical partner: Fritz Kreisler’s first Guarneri, the 1735 ‘Mary Portman’ Guarneri del Gesù. On generous loan from Clement and Karen Arrison from the Stradivari Society of Chicago, both the owner and I refer lovingly to her as Miss Mary. Listening to Kreisler’s playing and the sound of Miss Mary under my ears, one can grasp the qualities that must have drawn him to the instrument: a powerhouse G string, which Guarneris’ are known for, combined with a magnetic sweetness of the middle strings that she lets you unlock only if you play her in a certain way – with a slower bow, drawing the sound out with a loving yet heavy rub of the string.

Eugène Ysaÿe

Encore: Sonata for Two Violins: Poco lento, maestoso – Allegro fermo

To close this album, I pay tribute to a source of inspiration that has guided me in my artistic journey: my friendships with other violinists. If this recording were to be a recital, this last track would be its encore. The opening movement of Ysaÿe’s Sonata for Two Violins with my dear friend, the extraordinary violinist Stella Chen.

Ysaÿe dedicated his set of sonatas to six of his closest friends, all incredible violinists in their own right. The relationships with his colleagues were always rooted in mutual respect and admiration. In the case of the 2nd sonata that opens this album, Ysaÿe even lent Jacques Thibaud his Stradivarius violin for some of his younger colleague’s concerts. But Ysaÿe’s relationships with other violinists were also built on a principle that I cherish and that is common to musicians from any era: Learning from one another. It is a delight to share ideas with colleagues and deepen one’s understanding of a piece or some aspect of violin playing in the process. What in the trade, we hear referred to as nerding out.

It was in 1915 when Ysaÿe wrote his Sonata for Two Violins, a piece that was never published during his lifetime. It was a gift to the most royal of his students, Queen Elisabeth of Belgium. The work is full of challenging, virtuosic passages; it is far from a piece written for an amateur. There isn’t any record of Ysaÿe and the Queen playing it in public, but one can only assume that her violin skills were quite advanced to even attempt to play through this challenging work.

The composer develops a heroic narrative through the heavy use of double stops in both parts. The musical discourse is centred around the four-note motive that appears at the very top, played by both violins in unison. The stately opening section, Poco Lento – Maestoso, is full of drama and richness in the harmonies. The huge dynamic range that Ysaÿe demands of his performers is immediately on display, featuring sudden descents from forte to pianissimo that will be a constant throughout the sonata.

Just as in his six solo sonatas, Ysaÿe is showcasing the virtuosity of violin playing in his composition. The Allegro fermo that follows the opening section is full of rapid arpeggios, syncopated accents and finger twisting chords. This focus on virtuosity, a feature in Ysaÿe’s whole opus, is complementary to the overall rhapsodic character of this work. The obsessive Ysaÿe carefully indicates every push and pull of the tempo with his expressive markings. He even specifies the type of sound (such as sensibile and perdendosi) that he expects from the performers.

The soaring and feather-like sensibile melodies are abruptly interrupted by a fugue, a heavy Allegro Giusto. The music tries to escape into the realm of the dolce, only for the fugal material to come back once again. The recapitulation follows, a different take on earlier material. This time the second violin is at the helm of most melodies. Ysaÿe steps up even more the brilliance with a final frenzy, a race to the end. The unison motive, augmented and with an added note, makes one last appearance, bringing back the opening Lento Maestoso to bookend the commanding work.

Throughout the piece, Ysaÿe shows off his impressive compositional skills, creating a complex sound world full of dissonances and colourful harmonies. The sonata is intriguing yet at times confusing. So many different materials and even styles are contained within the work, competing and interrupting one another. One can only wonder if Ysaÿe was still searching for his own voice. Less than a decade later, Ysaÿe did achieve a greater structure and focus in his materials, in the Six Sonatas.

I could not have picked a better choice for this collaboration. Stated simply, Stella is an incredible violinist. She is also the most recent winner of the Queen Elisabeth Violin Competition. That competition had been the dream of the most renowned of Belgian musicians, Eugène Ysaÿe, and several years after his death, in 1937, Queen Elisabeth honoured Ysaÿe by sponsoring the creation of such a competition. The competition even bore the name Ysaÿe during its first two editions. To this day, all candidates are required to play one of his six solo sonatas during the contest. Ysaÿe’s legacy lives on.

I have nerded out with Stella on countless occasions, whether in rehearsal, after a concert or back at the dorms at Juilliard. The late-night conversations among a small group of musicians, mostly violinists, were a staple of our time at Juilliard. I reflect on those spontaneous exchanges, full of wisdom, during lonely hours of daily practice. I’ve dearly missed those exchanges since the pandemic started, and I will enjoy them even more once they come back.

© Francisco Fullana

Francisco Fullana

A native of Mallorca in the Balearic Islands of Spain, Francisco Fullana is making a name for himself as both a performer and a leader of innovative educational institutions. A recipient of the 2018 Avery Fisher Career Grant, he has performed as soloist with orchestras such as the Münchner Rundfunkorchester, Spanish Radio Television Orchestra, Argentina’s National Orchestra, Venezuela’s Teresa Carreño Orchestra, and numerous U.S. ensembles including the Saint Paul and Philadelphia Chamber Orchestras, the Buffalo Philharmonic, and the Vancouver, Pacific, Alabama, and Maryland Symphony Orchestras. He has worked with such noted conductors as the late Sir Colin Davis, Gustavo Dudamel, Alondra de la Parra, Christoph Poppen, Jeannette Sorrell, and Joshua Weilerstein.

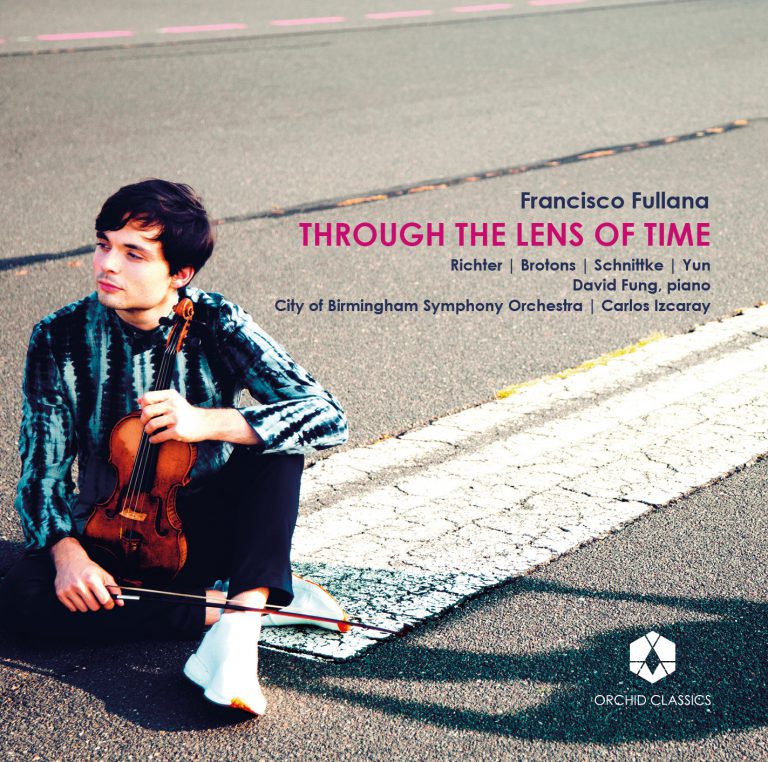

In 2018 Orchid Classics released Francisco’s acclaimed debut recording Through the Lens of Time, which includes Max Richter’s 2012 composition The Four Seasons Recomposed—performed with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra under Carlos Izcaray—along with other 20th century works exploring connections with the baroque era, by Alfred Schnittke, Salvador Brotons, and Isang Yun. Fullana’s love for the sound of gut strings has blossomed into an artistic partnership with the Grammy Award winning baroque ensemble Apollo’s Fire, both in performance and in the recording of Spanish and Italian baroque music.

Active as a chamber musician, Francisco is a performing member of The Bowers Program at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and has participated in the Marlboro Music Festival, the Musicians from Marlboro tours, the Perlman Music Program, the Da Camera Society, and the Moab, Music@Menlo, Mainly Mozart, Music in the Vineyards, and Newport music festivals. His musical collaborators have included Viviane Hagner, Nobuko Imai, Charles Neidich, Mitsuko Uchida, and members of the Guarneri, Juilliard, Pacifica, Takács, and Cleveland Quartets.

Born into a family of educators, Francisco is a graduate of the Royal Conservatory of Madrid, where he matriculated under the tutelage of Manuel Guillén. He received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from The Juilliard School following studies with Donald Weilerstein and Masao Kawasaki, and holds an Artist Diploma from the USC Thornton School of Music, where he worked with the renowned violinist Midori.

In 2015 Francisco was honoured with First Prize in Japan’s Munetsugu Angel Violin Competition, as well as all four of that competition’s special prizes including the Audience and Orchestra awards. Additional awards include First Prizes at the Johannes Brahms and Julio Cardona International Violin Competitions, the Pro Musicis International Award, and the Pablo Sarasate Competition.

Francisco is a committed innovator, leading new institutions of musical education for young people. He is a co-founder of San Antonio’s Classical Music Summer Institute, where he currently serves as Chamber Music Director. He also created the Fortissimo Youth Initiative, a series of music seminars and performances with youth orchestras, which aims to explore and deepen young musicians’ understanding of 18th-century music. The seminars are deeply immersive, thrusting youngsters into the sonic world of a single composer while inspiring them to channel their overwhelming energy in the service of vibrant older styles of musical expression. The results can be galvanic, and Francisco continues to build on these educational models.

Francisco Fullana performs on the 1735 “Mary Portman” ex-Kreisler Guarneri del Gesù violin, kindly on loan from Clement and Karen Arrison through the Stradivari Society of Chicago.

Stella Chen

Lauded for her “phenomenal maturity” and “fresh and spontaneous, yet emotionally profound and intellectually well-structured performance” (Jerusalem Post), American violinist Stella Chen has been bursting onto the world stage following her first prize win at the 2019 Queen Elizabeth International Violin Competition. In the last year alone, Stella was named a recipient of a prestigious 2020 Avery Fisher Career Grant and 2020 Lincoln Center Emerging Artist Award.

Stella enjoys a varied musical life including performances all over the world as soloist and chamber musician. She has appeared with orchestras including the Belgian National Orchestra, Brussels Philharmonic, Welsh National Symphony Orchestra, the Luxembourg Philharmonia, and many others. As recitalist, Stella has played in venues including the Kennedy Center, Phillips Collection, WQXR’s Greene Space, Rockefeller University, and Ravinia’s Bennett Gordon Hall. Debuts in the upcoming season include those with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Kremerata Baltica. Stella is also a member of the Bowers Program at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center starting in the 2021-2022 season.

A graduate of the Harvard/New England Conservatory Dual Degree Program, Stella received a Bachelor of Arts in psychology with honours from Harvard University. Stella is currently completing her studies as C.V. Starr doctoral candidate at the Juilliard School, where she serves as a teaching assistant for her long-time mentor Li Lin; she is writing her dissertation on one of her favourite pieces of music, Schubert’s Fantasie for Piano and Violin. She is also a professional studies candidate at Kronberg Academy. Teachers and mentors include Mihaela Martin, Li Lin, Donald Weilerstein, Itzhak Perlman, and Miriam Fried. She plays the ‘Huggins’ 1708 Stradivarius violin, generously on loan from the Nippon Music Foundation.