Artist Led, Creatively Driven

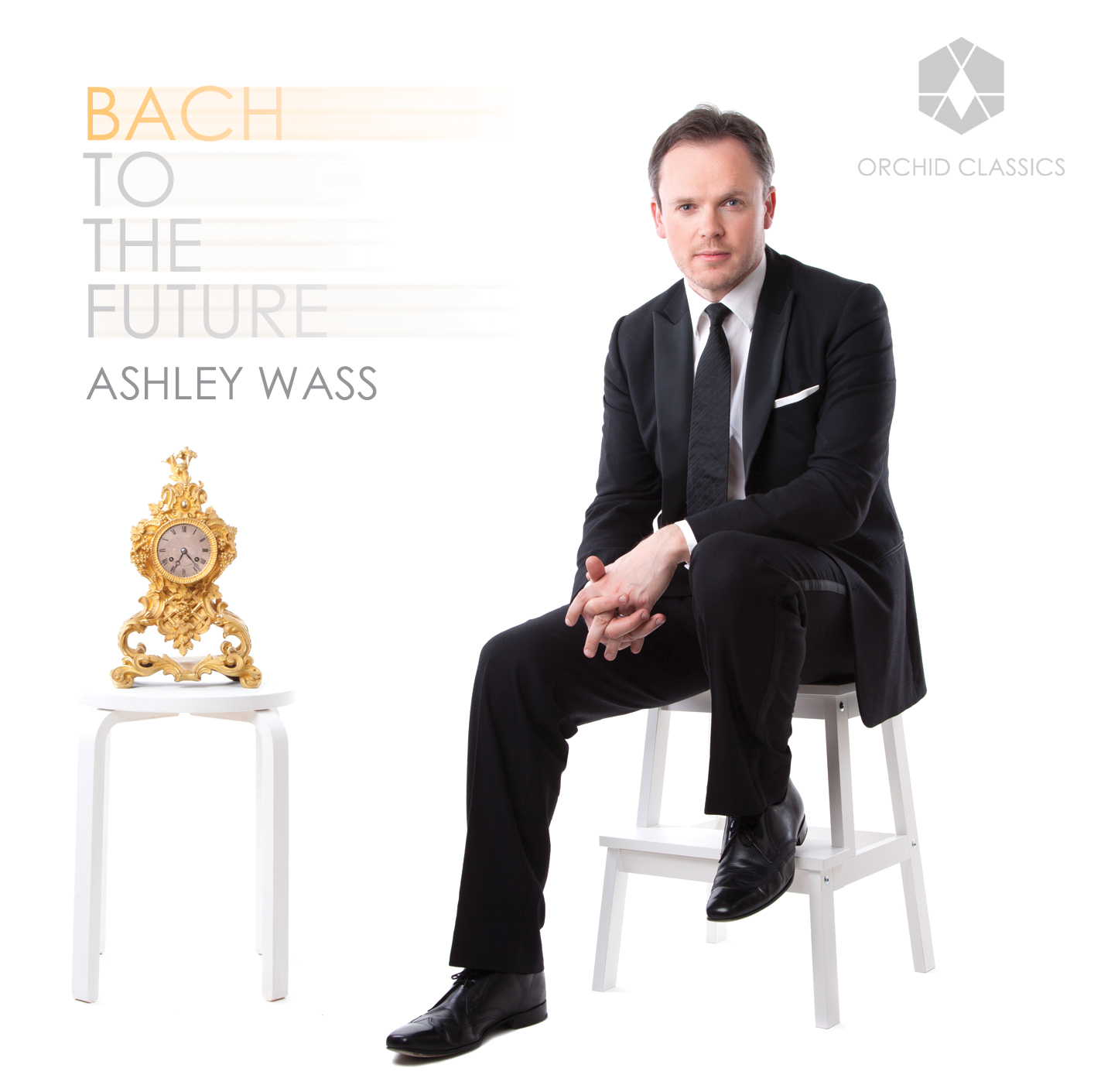

Bach to the Future

Ashley Wass

Release Date: September 2013

ORC100033

J.S. BACH (1685-1750) arr. G. Kurtág (b.1926)

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, BWV687 *

ALBAN BERG (1885-1935)

Piano Sonata, Op.1

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN(1770-1827)

Six Bagatelles, Op.126

I. Andante con moto

II. Allegro

III. Andante

IV. Presto

V. Quasi Allegretto

VI. Presto – Andante amabile e con moto – Tempo I

J.S. BACH arr. BUSONI

Chorale Prelude ‘Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ’, BWV639

FERRUCIO BUSONI(1866-1924)

Fantasia nach J.S. Bach, BV253

SAMUEL BARBER(1910-1981)

Piano Sonata in E flat minor, Op.26

I. Allegro energico

II. Allegro vivace e leggiero

III. Adagio mesto

IV. Fuga: Allegro con spirito

J.S. BACH arr. KURTAG

Sonatina from Actus Tragicus, ‘Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit’, BWV106 *

Ashley Wass (piano)

* with Ron Abramski (piano)

BACH TO THE FUTURE

The 21st Century has so far been witness to many curious developments – the popularity of soundbite social media, the wearing of Crocs as an acceptable form of fashion, TVs that do almost everything bar cook a full English, increasingly unpredictable weather patterns – but by far the strangest of all has been the unstoppable rise of the autobiography, most often penned (as it were) by footballers, pop-stars and reality TV characters who’ve barely emerged from puberty. Well, my terrible teens are long gone but I still like to think of myself as a young musician, so, for the sake of social solidarity, I’ve opted for an ‘if you can’t beat ’em join ’em’ attitude and have chosen for this disc – the first mixed repertoire recording over which I’ve had complete control – a series of pieces that have been particularly significant in my life and career to date. Of course, the beauty of musical autobiographies is that they are, at least when confined to the space of a single CD, mercifully short. No inane descriptions of breakfast cereals or days in the park to be found here and, booklet notes aside, you’re safe from terrible prose. So I hope you’ll forgive my self-indulgence and simply enjoy what is, I believe, a series of great musical masterpieces, from which you’ll inevitably garner your own context and meaning.

The first problem one encounters when planning a (semi-)autobiographical disc is how to restrict oneself to a mere 75 minutes of music. As pianists we’re spoilt; there are simply too many great pieces to fit into a life, so the vast majority of us naturally migrate towards areas of the repertoire with which we feel particularly comfortable. Although the range of composers I’ve tackled over the years is extensive, the works I’ve truly enjoyed have most often had one thing in common; a sense of counterpoint such that renders every note critical. Thus, it’s perhaps no surprise that all the music on this disc, despite covering several centuries, can be related, either directly or indirectly, through style, form or structure, to Bach, the composer who the late Maria Curcio, one of my former teachers, often referred to as “the Grandfather of music”. Hence the title Bach to the Future can be taken almost literally as we traverse the musical ages, from good ol’ (faithfully transcribed) J.S. himself to Barber’s masterful sonata of the mid-20th century.

Berg’s Piano Sonata, written as a single B minor movement in traditional sonata form, is a remarkable exercise in structural unity, chromaticism and counterpoint. Neurotic and highly intellectual, yet also organic, it is never at any moment during its 12-minute duration anything less than vein-poppingly intense. The form of the piece is derived entirely from the mysterious opening line (the end cadence [onto a B minor chord] of which, in the context of this programme, is intended to bring closure to the unresolved chord of F sharp which ends the preceding Bach/Kurtág), moulding, transforming and transfiguring the tonally elusive introductory motifs (am I the only one who’s reminded here of the opening of Star Trek?) through canonic conflict to glue together the material as an expressive whole. It’s a work I’ve loved for as long as I’ve known it, but it must be acknowledged as one which divides opinion; I remember, for example, a former teacher dismissing it as “music containing too many orgasms”. Nonetheless, I’ve always considered it a wonderful and compelling piece to perform, and it’s appeared regularly in my recital programmes over the years. On one particularly memorable occasion, during my Paris debut, a high F sharp string broke, causing some unfortunately hilarious gamelan-like effects throughout (especially painful in the final bars). It also featured (more happily) in a London concert I gave in 2000 which ultimately led to me being chosen for the BBC’s New Generation Artist Scheme. Being an NGA was a hugely valuable experience and one which was of enormous benefit to my career. It’s somehow gratifying to think that Mr. Berg played a significant role in my selection.

If it’s really true, as is often claimed, that late Beethoven is best left until your senior years then I broke the rules, for my initial encounter with the Op.126 Bagatelles came when I was but 12 or 13. No.3 was the first to find its way into my fingers (it fitted perfectly into the short mixed programmes so commonly required for the type of minor competitions, auditions and exams one tackles at that age) while No.4 followed soon after, simply by virtue of it making a great encore. The rest had to wait until I entered the Royal Academy of Music some years later. Riddled with counterpoint (fugues, canons and inventions ahoy!) and condensed expressive intensity, they are a case study for those exploring the all-encompassing world of Beethoven. Nos.2 and 6 refute the misconception that he lacked a sense of humour, No.3 explores the very reaches of profundity and inner-peace – a calm shattered by the explosive juxtaposition of aggression and charm to be found in No.4 – and Nos.1 and 5 are elegant, earnest and full of grace. Above all else, these are infinitely strange pieces that are forever destined to remain strikingly original and obstinately elusive.

(Incidentally, if you’re ever bored try to spot the Batman theme in the left hand of No.2. Your prize? A lifetime of listening to the piece without being able to shake the image of the Caped Crusader. You’re welcome.)

It was while at the Academy that I began regular lessons with Maria Curcio, and these Bagatelles were among the pieces I studied with her most intensely. Indeed, she helped me prepare them as an integral part of my programme for the 1997 London International Piano Competition, the event that launched my recording career, and invited me to play them for her in a public masterclass shortly after the competition had passed. It was known to me that an artist manager from a large agency was planning to attend this class and I informed Maria before we began in the hope she might be particularly kind in her comments. Sure enough, as I finished playing, she strode onto the stage, leaned over and quietly asked me if the ‘agent man’ was definitely there, muttered an unprintable insult about him when I nodded, and then turned to the audience, raised her voice and launched into an exaggerated appraisal of the merits of my playing and my potential for a glittering career, quite obviously aimed at securing me the management deal of the decade. Ordinarily, of course, this would be fine and wonderful, but this particular occasion happened to be the first (and last) time Maria wore a lapel microphone, and she clearly hadn’t grasped the notion that even the quietest whisper would be broadcast to everyone in attendance. And so it was that the agent heard – and evidently took offence at – her invidious remark, and I glumly watched him collect his coat and storm from the hall as she eulogized, blissfully unaware of the umbrage she’d caused. Unsurprisingly, I never heard from him – or his company – again.

One of the perks of being a BBC NGA is the opportunity to record in the studio for Radio 3, and one of the first works I was asked to commit was Busoni’s Fantasia nach J.S. Bach. Written shortly after the death of his father, it’s an immensely powerful and spiritual work, emerging from despairingly murky low scales and arpeggios (the F minor tonality is pre-empted here by Ich ruf’ zu dir in the same key), and journeying through reflection, redemption and – ultimately – resignation. Neither a paraphrase nor a transcription, the Fantasia takes the form of what the composer referred to as a Nachdichtung: that is, the immersion or translation of an existing text into a new musical style. Direct quotes from three of Bach’s organ works are expanded in Busoni’s unique harmonic style (“like Bach with wrong notes”, as one esteemed colleague once commented to me), with regular use of his ‘death motif’ (three repeated notes or chords) adding to the gloom. This is indeed, as Busoni himself remarked, ‘music from the heart’, and it’s very much a music which ought to be heard in the concert hall with greater frequency.

Every pianist has a ‘party piece’ and, for many years, mine was Barber’s Piano Sonata. It’s a work that saw me through countless competitions, auditions, exams and concerts during my college years – and long after – and it’s something I’ve often been advised to record. I still remember clearly the first time I heard it (on a school trip to the Leeds Competition semi-finals in 1993); I determined immediately it was something I simply had to learn, indelibly struck as I was by the brilliance and dynamism of the famous fugue finale. Written in 1949 for the 25th anniversary of the League of Composers, the Sonata encompasses many popular techniques of the 20th century, including bitonality, tone rows, jazz, ostinati and developing variation, as well as incorporating the kind of contrapuntal skill and developmental mastery associated with the baroque age. The overwhelming mood, from the very first dramatic and uncompromising notes, is dark; the opening movement appears apocalyptic, the second is sardonic and twisted – as if peering at a Mendelssohnian scherzo through the distorted mirrors of a fun-fair – and the third is dirge-like and anguished (with echoes of Prokofiev’s War Sonatas), the left-hand ostinato seeming to symbolise the unfeeling and unrelenting ticktock of fate. The fugue, incorporating up to six voices at times, is masterful in its execution, using jazz-like syncopation to crank up the tension until the music can bear no more and fragments into a cataclysmic quasi-cadenza which heralds the coda. Always a popular and powerful piece with audiences, it remains an integral part of my performing repertoire, and it’s a huge pleasure to feature it here.

The three short Bach transcriptions, one by Busoni and two by Kurtág, form the framework for this programme, creating a kind of symmetry to its structure. Ich ruf’ zu dir, taken from the Orgelbüchlein, found its way into my debut Wigmore performance many years ago and is surely amongst the most precious and perfect of Man’s creations. For the two Kurtág transcriptions that bookend the recital (“all come from dust, and to dust all return”), I owe not one but two debts of gratitude. Firstly to my former student Antoine Francoise, who introduced the pieces to me and used them in similar fashion for his final recital at the Royal College of Music (with his regular duo partner Robin Green), and secondly to Ron Abramski, my distinguished companion on this disc. In a programme full of autobiographical intent, it seems fitting to work alongside Ron, my oldest and dearest friend, and to (yes, I admit it) steal an inspired idea from my first full-time pupil (at this point I’d like to direct you to the infinite wisdom of Igor Stravinsky; “lesser artists borrow, great artists steal”). The two works in question, Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir and Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit are unspeakably gorgeous, communicating a depth of feeling and purity of which words are not capable. The latter shares the same key (E flat) as the Barber, but could not be further removed in style or mood; it brings to mind the wonderfully eloquent quote of Douglas Adams – “Bach tells you what it’s like to be the universe” – and its inclusion is intended to bring a little celestial serenity to this disc’s conclusion.

Finally, no self-penned, self-indulgent book (or, in this case, CD) is worth its salt without a corny dedication and mine is to my daughter, Amelia Pearl, who was born just a short while before the vast majority of this disc was recorded. Looking back, I like to think of the long and sleepless nights as extra preparation time for the sessions. I’m not sure that’s how I felt at the time.

© Ashley Wass

ASHLEY WASS

Ashley Wass is firmly established as one of the leading performers of his generation. Described by Gramophone Magazine as a ‘thoroughbred who possesses the enviable gift to turn almost anything he plays into pure gold’, he is the only British winner of the London International Piano Competition, prizewinner at the Leeds Piano Competition, and a former BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artist.

Increasingly in demand on the international stage, he has performed as soloist with numerous leading ensembles, including all of the BBC orchestras, the Philharmonia, Orchestre National de Lille, Vienna Chamber Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, RLPO, and under the baton of conductors such as Sir Simon Rattle and Osmo Vanska.

Ashley is also much in demand as a chamber musician – performing regularly at many of the major European festivals, and at the Marlboro Music Festival, playing chamber music with musicians such as Mitsuko Uchida, Richard Goode and members of the Guarneri Quartet and Beaux Arts Trio. He has performed at many of the world’s finest venues including Wigmore Hall, Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center, the Vienna Konzerthaus and Carnegie Hall in New York.

Ashley Wass is the Artistic Director of the Lincolnshire International Chamber Music Festival. The Festival has grown from strength to strength during his tenure, with sold-out performances of challenging repertoire and broadcasts on BBC Radio 3. Currently a Professor of Piano at the Royal College of Music, London, Ashley is also an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music.

www.ashleywass.com

www.facebook.com/AshleyWassPiano

Twitter follow @ashley_wass