Artist Led, Creatively Driven

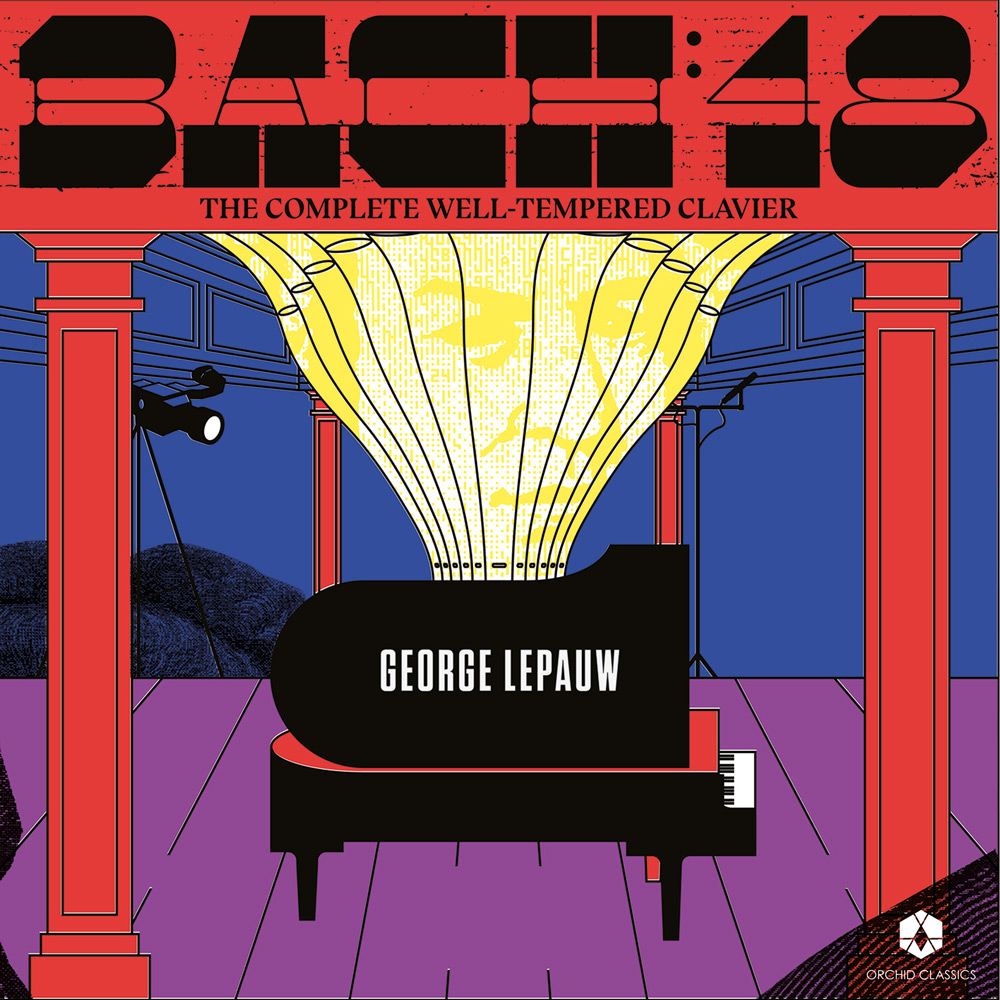

BACH48

The Complete Well-Tempered Clavier

George Lepauw

Release Date: February 14th 2020

ORC100107

Bach48: Journey Into the Well-Tempered Clavier

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

The Well-Tempered Clavier BWV 846-893

Book I: CDs 1 & 2

Book II: CDs 3, 4 & 5

George Lepauw, piano

BOOK I

CD 1

1 Prelude No.1 in C major, BWV846 2.59

2 Fugue No.1 in C major, BWV846 1.46

3 Prelude No.2 in C minor, BWV847 2.17

4 Fugue No.2 in C minor, BWV847 1.44

5 Prelude No.3 in C# major, BWV848 1.25

6 Fugue No.3 in C# major, BWV848 2.24

7 Prelude No.4 in C# minor, BWV849 4.32

8 Fugue No.4 in C# minor, BWV849 3.55

9 Prelude No.5 in D major, BWV850 1.38

10 Fugue No.5 in D major, BWV850 2.29

11 Prelude No.6 in D minor, BWV851 1.20

12 Fugue No.6 in D minor, BWV851 1.57

13 Prelude No.7 in E♭ major, BWV852 4.44

14 Fugue No.7 in E♭ major, BWV852 1.58

15 Prelude No.8 in E♭ minor, BWV853 5.05

16 Fugue No.8 in D# minor, BWV853 4.48

17 Prelude No.9 in E major, BWV854 1.58

18 Fugue No.9 in E major, BWV854 1.11

19 Prelude No.10 in E minor, BWV855 3.38

20 Fugue No.10 in E minor, BWV855 1.12

21 Prelude No.11 in F major, BWV856 1.29

22 Fugue No.11 in Fmajor, BWV856 1.25

23 Prelude No.12 in F minor, BWV857 3.15

24 Fugue No.12 in F minor, BWV857 4.16

Total time 63.35

CD 2

1 Prelude No.13 in F# major, BWV858 2.39

2 Fugue No.13 in F# major, BWV858 2.03

3 Prelude No.14 in F# minor, BWV859 1.16

4 Fugue No.14 in F# minor, BWV859 4.07

5 Prelude No.15 in G major, BWV860 1.06

6 Fugue No.15 in G major, BWV860 2.49

7 Prelude No.16 in G minor, BWV861 3.37

8 Fugue No.16 in G minor, BWV861 2.24

9 Prelude No.17 in A♭ major, BWV862 1.32

10 Fugue No.17 in A♭ major, BWV862 2.08

11 Prelude No.18 in G# minor, BWV863 2.34

12 Fugue No.18 in G# minor, BWV863 3.22

13 Prelude No.19 in A major, BWV864 1.21

14 Fugue No.19 in A major, BWV864 2.34

15 Prelude No.20 in A minor, BWV865 1.21

16 Fugue No.20 in A minor, BWV865 4.48

17 Prelude No.21 in B♭ major, BWV866 1.47

18 Fugue No.21 in B♭ major, BWV866 1.48

19 Prelude No.22 in B♭ minor, BWV867 3.20

20 Fugue No.22 in B♭ minor, BWV867 3.14

21 Prelude No.23 in B major, BWV868 1.41

22 Fugue No.23 in B major, BWV868 2.01

23 Prelude No.24 in B minor, BWV869 7.15

24 Fugue No.24 in B minor, BWV869 9.16

Total time 70.10

BOOK II

CD 3

1 Prelude No.1 in C major, BWV870 4.28

2 Fugue No.1 in C major, BWV870 1.44

3 Prelude No.2 in C minor, BWV871 2.22

4 Fugue No.2 in C minor, BWV871 2.35

5 Prelude No.3 in C# major, BWV872 2.40

6 Fugue No.3 in C# major, BWV872 1.34

7 PreludeNo.4 in C# minor, BWV873 6.14

8 Fugue No.4 in C# minor, BWV873 2.32

9 Prelude No.5 in D major, BWV874 5.46

10 Fugue No.5 in D major, BWV874 2.26

11 Prelude No.6 in D minor, BWV875 1.31

12 Fugue No.6 in D minor, BWV875 2.10

13 Prelude No.7 in E♭ major, BWV876 3.24

14 Fugue No.7 in E♭ major, BWV876 2.28

15 Prelude No.8 in D# minor, BWV877 4.28

16 Fugue No.8 in D# minor, BWV877 3.25

Total time 49.53

CD 4

1 Prelude No.9 in E major, BWV878 6.47

2 Fugue No.9 in E major, BWV878 2.53

3 PreludeNo.10 in E minor, BWV879 4.59

4 Fugue No.10 in E minor, BWV879 3.39

5 Prelude No.11 in F major, BWV880 3.20

6 Fugue No.11 in F major, BWV880 1.52

7 Prelude No.12 in F minor, BWV881 6.52

8 Fugue No.12 in F minor, BWV881 2.37

9 Prelude No.13 in F# major, BWV882 4.42

10 Fugue No.13 in F# major, BWV882 3.07

11 Prelude No.14 in F# minor, BWV883 3.47

12 Fugue No.14 in F# minor, BWV883 5.56

13 Prelude No.15 in G major, BWV884 2.29

14 Fugue No.15 in G major, BWV884 1.33

15 Prelude No.16 in G minor, BWV885 4.44

16 Fugue No.16 in G minor, BWV885 4.56

Total time 64.18

CD 5

1 Prelude No.17 in A♭ major, BWV886 5.53

2 Fugue No.17 in A♭ major, BWV886 3.08

3 Prelude No.18 in G# minor, BWV887 6.14

4 Fugue No.18 in G# minor, BWV887 4.40

5 Prelude No.19 in A major, BWV888 2.09

6 Fugue No.19 in A major, BWV888 1.40

7 Prelude No.20 in A minor, BWV889 3.44

8 Fugue No.20 in A minor, BWV889 2.01

9 Prelude No.21 in B♭ major, BWV890 9.10

10 Fugue No.21 in B♭ major, BWV890 2.31

11 Prelude No.22 in B♭ minor, BWV891 2.39

12 Fugue No.22 in B♭minor, BWV891 5.25

13 Prelude No.23 in B major, BWV892 2.39

14 Fugue No.23 in B major, BWV 892 3.33

15 Prelude No.24 in B minor, BWV893 2.29

16 Fugue No.24 in B minor, BWV893 2.33

17 Prelude No.1 in C major, BWV846 2.45

Total time 63.17

Bach48

Recording Johann Sebastian Bach’s complete Well-Tempered Clavier was born out of my desire to become a more complete musician, and a better human being. While this masterwork is a necessary part of any serious pianist’s life, it is also at the root of much of the greatest music that has come since, having deeply influenced composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Brahms, Debussy, Shostakovich and so many more. Hans von Bülow, the 19th century pianist and conductor, referred to the Well-Tempered Clavier as music’s “Old Testament”, in association with Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas as music’s “New Testament.” It has been my intention to record both of these “testaments” in my journey to be the best musician I can be and delve ever deeper into the mysteries of the human soul. As I send this recording out into the world, I ready myself to begin the Beethoven cycle… For me this is a sacred quest.

The Well-Tempered Clavier is the title given to this two volume collection Bach composed between 1717 and 1742, each containing 24 pairs of Preludes and Fugues in all the major and minor keys of the twelve note Western scale, which adds up to 48 pairs of pieces or 96 individual pieces. A prelude is essentially a free improvisation without any predetermined structure, whereas a fugue is a very formal and rule-driven work that interlaces several staggered voices in a contrapuntal adventure emphasizing harmonic struggle before the final resolution of its disparate parts. As a famous keyboardist and organist, Bach was equally known as one of the greatest improvisers of all times and as a masterful composer of fugues: in The Well-Tempered Clavier he outdid himself in showcasing his boundless imagination and mastery of the hardest compositional techniques.

Bach had several intentions with this work: to affirm his legacy; to give musicians a model of composition and a wide range of technical challenges; and to convince the musical world that the “well tempered” tuning system of keyboard instruments was the way forward, a major point of debate at that time and a complex topic you can learn more about in books and on our website. He also used this music to wrestle with every imaginable existential question he might have had, and I have grown to view this work as Bach’s very own Confessions. The “Bach 48” as it is sometimes known, is a foundation of Western music, akin to the Magna Carta, and upon which musicians have built ever since.

The Well-Tempered Clavier plays with notions of time and space through notes and rhythms assembled by Bach the musician architect. The very beginning of this epic, the first Prelude in C Major, progressively brings light out from the shadows, and yet we might be led to think its rolling chords never really have a definite start: like waves in the ocean, they just are. The end of each piece leads us into the next, in a forward motion we do not want to stop, other than to breathe. Each prelude, each fugue, is a work finite yet always generator of the next adventure. That is why I felt it necessary to play the very first piece of The Well-Tempered Clavier again, the very same opening Prelude in C Major, after the very last fugue in this recording: the end of the journey is not final, cannot be final, but is an opportunity to engage another loop in the infinity of our life experience, of our universe. Try again! There is more to learn, and there are more treasures to be found. Indeed, no two traversals are the same, which is as true for the performer as it is also for the listener. This music is meant to be heard, listened to, felt deep inside, and as often as possible. The meaning of life itself is to be found in this music, if one’s heart is truly open… This is a soul awakener, and a loyal companion to our lives under all circumstances.

I did not jump into this recording project unprepared. In addition to decades of practice and years of studying The Well-Tempered Clavier, I felt it necessary to gain greater insight into Johann Sebastian Bach’s experience of the world and to understand the origin of his greatest masterwork. Hence I set out to explore the region of Thuringia, Germany in the Winter of 2017, retracing Bach’s footsteps in the places where he grew up, worked, and died. These travels convinced me to return to Germany six months later to record the entire Well-Tempered Clavier in the Jakobskirche, Weimar’s oldest church, a few blocks from where Bach had served as Konzertmeister at the ducal court of Saxe-Weimar and near the local Bastille prison where he had been detained for four weeks in 1717. This imprisonment at the age of thirty-two dramatically ended Bach’s tenure in Weimar, but also gave him time to meditate on where he stood in his life, and to envision what he still wanted to achieve: it was while in jail that he developed his initial idea for The Well-Tempered Clavier…

I did not want this album to be limited to a straightforward, traditional recording, as in this 21st century it is increasingly difficult to reach younger listeners. Today, visual content and narrative are critical to reaching an audience in order to share one’s passion, hard work andmore importantly, the great masterworks of the past. Thus, I conceived the Bach48 Album to include, in addition to the audio, a film version of the recording as well as a special documentary film which details my explorations of Bach’s Germany, bringing the audience along in the (re)discovery of The Well-Tempered Clavier’s origin story.

Directed by Martin Mirabel and Mariano Nante, the Voyage Into the Well-Tempered Clavier film follows me from Bach’s birthplace in Eisenach to his grave in Leipzig, passing through other important sites along the way including the very prison cell where Bach was held in 1717, three hundred years before I made the recording. This was a most moving experience for me personally, helping me feel closer to Bach the man in all his imperfect glory, and giving me plenty of material beyond pure music to absorb before attempting this recording.

The conditions under which this album was made were unique in my life, simultaneously deeply challenging as well as wonderfully satisfying. The greatest difficulty was overcoming the emotional pain of losing my paternal aunt Nicole Laury-Lepauw just six weeks before the start of the recording, an incredible woman who was such an important part of my life and whose humanism, constant curiosity, and love of music made our many conversations and shared experiences ever thrilling. To her memory I dedicate this Bach48 Album.

I was lucky, through all this, to have had the best team anyone could hope for in this type of adventure. Audio producer Harms Achtergarde was a true joy to work with, a man of great talent, professionalism, patience, and passion whose ear was infallible. I felt that we were both focused on bringing the best out of this music and out of me. The recording was also made in front of cameras, and while in most situations this would prove to be a frustrating distractionand constraint, filmmakers Martin Mirabel and Mariano Nante gave me the support I needed to be at ease. Each one of them in his own unique way added his spirit to this recording, pushing me to be at my best, telling me when I fell short but also giving me heartfelt congratulations, and hence confidence, when I outdid myself. Harms, Martin and Mariano understood my musical vision perfectly, which gave me greater strength to achieve it. Anne Ludwig was our discreet assistant who helped us all accomplish this tremendous project in just five full days and nights, in the unparalleled intimacy of the Jakobskirche (well-known to Bach) which became our temporary home that magical Summer week.

Bach’s name in German means “brook” or “stream”. While perhaps apocryphal, Beethoven who admired Bach without limit is thought to have said (but certainly someone said so, if not him!): “Nicht Bach, sondern Meer sollte er heißen…” (“Not brook, but rather ocean should he be called…”). Intruth, Bach is pure infinity and multiplicity, brook and ocean all at once, and his declinations in music are as rich as the myriad forms and states of water. His music flows always, renews itself endlessly, cycles through the atmosphere and comes back tous refreshed and filtered, allowing us to fill ourselves with it. Notes and rhythms form currents and countercurrents, raging tempests and placid ponds, hidden sources and river rapids, creating rich ecosystems filled with life, where even death feeds back into the evolutionary spiral. In Bach’s music, optimism is ever-present, and the sun rises always, no matter how frightful the demons, or how deep the suffering. Through my time navigating his music, I have come to realize that we need Bach for our souls just as much as we need water for our bodies.

There is so much more to say about this multi-year and deeply rewarding project, about the amazing people who have been involved far and wide from Chicago to Weimar, Buenos Aires to Paris, and beyond; and of course there is just so much to say about Bach and this music. There are magical stories about Baltic cocktail parties, flying parasols and mediaeval beer, about life and death, about finding ground in times of upheaval, about following hidden signs and falling in love, and of discovering the only piano this recording could be made on, 850 kilometers away from the recording venue… Because this space is finite, my passionate team and I built a companion website to continue sharing all those stories and bring lovers of Bach together.

This project could not have been made in the real world without the supportof the foundations and donors who so generously contributed to its success and trusted my vision, all of whom are thanked at the end of this booklet. Of note I must make particular mention of, and express my deep gratitude to, those whose true friendship and essential early and significant support got this project off the ground: Christopher Hunt, Herbert Quelle, Chaz Ebert, and Tim and Paula Friedman. I have also been lucky to have had the unflinching and loving support of my family, which has meant so much to me over the years of ups and downs. The dedication I have put into this project is an expression of all the goodwill I have received to bring it into existence, and I consider the Bach48 Album to be a co-creation of all those who have taken part in it. Lastly, I am most excited to release this seminal album with Orchid Classics, thanks to its visionary leader Matthew Trusler. To all who have had a part in this adventure, I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Please visit, sign-up, recommend, and stay connected to the Bach48 Album and all things Well-Tempered Clavier at www.bach48.com.

I especially hope you, too, find meaning in this recording of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier.

George Lepauw, Paris, August 2019

George Lepauw

“A prodigious pianist” (Chicago Tribune) recognized for his “singing tone” (New York Times), and someone who “likes to shake it up” (Chicago Tribune), George Lepauw is an artist and cultural activist who uses music and the arts to inspire and bring people together, following upon Beethoven’s idea of “brotherhood”.

Named Chicagoan of the Year (2012) for Classical Music (Chicago Tribune), George represents the ideal 21st century musician, intensely focused on his art and wholly engaged with the world. In 2009 he had the honour of giving the World Premiere performance of a newly-discovered long-lost piano trio of Beethoven’s to great acclaim, which was followed by a highly-praised first recording with the Beethoven Project Trio for Cedille Records. In addition to his performance career, George is the Founder and President of the International Beethoven Project non-profit organization. From 2016 to 2018, George was Executive Director of the Chicago International Movies & Music Festival (CIMMfest), which allowed him to deepen his passion for film, an artform he has occasionally participated in as a producer, composer, and musician for over a decade. George, who grew up in France in a musical family (his grandfather Roger Lepauw was Principal Viola of the Paris Opera Orchestra as well as of the Orchestre de Paris; his father Didier Lepauw was First Violin with the Orchestre de Paris) began piano studies at the age of three in Paris with Aïda Barenboim (mother of pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim), and furthered his studies with Elena Varvarova, Brigitte Engerer, Vladimir Krainev, Rena Shereshevskaya, James Giles, Ursula Oppens, and Earl Wild, among others. He has degrees from Georgetown University (B.A. in Literature and Film Studies, and History), and from Northwestern University (M.M. in Piano Performance).

George is a frequent speaker and guest teacher at universities and “ideas festivals” as well as on radio and television, and also teaches piano to a select number of private students.

To stay up to date with George’s work, please visit www.georgelepauw.com.

‘You may find yourself with some unexpected free time in the coming weeks. Fill some of those spare hours with Lepauw’s Bach, and feed both brain and soul.’

‘Lepauw’s journey through these wonderful pieces is contemplative, commendably articulate and enhanced by unfailing linear clarity…’

Four Stars

BBC Music Magazine

‘…five CDs filled with exceptional recordings.’

Classic FM

‘An admirable way to explore one of the masterworks of keyboard repertoire’

‘This Well-Tempered Clavier is admirable and essential.’

‘I can confidently report that potential purchasers are in for something very special indeed…’