Artist Led, Creatively Driven

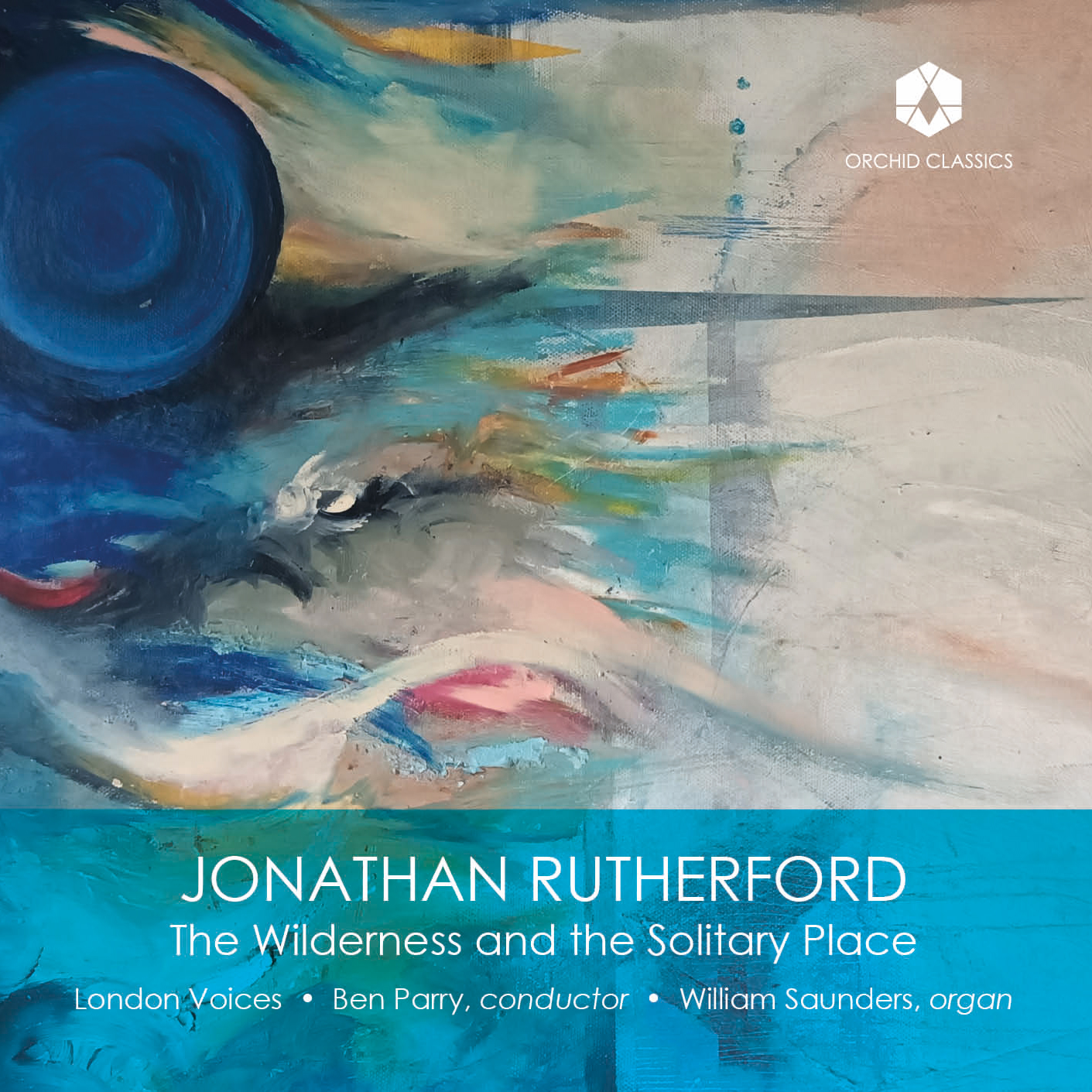

The Wilderness and the Solitary Place

Jonathan Rutherford

London Voices

Ben Parry, conductor

William Saunders, organ

Release Date: Nov 17th

ORC100268

THE WILDERNESS AND THE SOLITARY PLACE

Jonathan Rutherford (b.1953)

Isaiah 35 – Three Advent Carols (1998)

1. Rejoice, you barren land

2. The Sofferent thatte seeth evere seycrette

3. The Wilderness and the Solitary Place

Magnificat & Nunc Dimittis & Pilgrim’s Song

from “The Star Child” (1979-1985)

4. Magnificat & Nunc Dimittis

5. Pilgrim’s Song

6. Rejoice! Rejoice! (2010)

7. In the Bleak Midwinter (2015)

8. Blessèd is the Man who Finds Wisdom (2015)

9. For Behold, I Create New Heavens and a New Earth (2018)

Good Friday Music (Seven Last Words) (2015)

10. The First Word

11. The Second Word

12. The Third Word

13 . The Fourth Word

14. The Fifth Word

15. The Sixth Word

16. The Seventh Word

London Voices

Ben Parry, conductor

William Saunders, organ

Isaiah 35: Three Advent Carols (1998) was written for my brother Christian when he was music director of the choir of Little St Mary’s Church, Cambridge. I was asked, by Little St Mary’s Church, to set the words of Chapter 35 of Isaiah, from the Old Testament. At first, I could see no convincing way of setting the prose to music, and so I asked Jennifer Thorn, who had written the poem sung at the end of my piece An Intake of Breath, to adapt it into verse. She gave me the words which I have made the first of these three carols. While I was waiting for Jenny to write the verses, I found and read the lovely words, spoken by the character Isaiah, that open The Shearmen and Tailors’ Play (the Coventry Mystery Play) written probably between 1400 and 1425. This became the second carol. While composing these two settings, it then became obvious to me how I should make the music for a setting of the original words in the Bible, and provide a group of pieces that made a satisfactory whole.

Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (1985) come from the last scene of the opera, The Star-Child (1979-85), which combines the stories of two of Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales, The Young King and The Star-Child. I combined the two stories because they had so many similarities of plot, and had scenes which yearned for music and theatre. Both of the stories concerned the disparity between those living with opulent wealth, and those in miserable poverty. “Better that we had died of cold in the forest, or that some wild beast had fallen upon us and slain us” is a phrase which one of the woodcutters utters in the first scene of The Star-Child. In the action, the eponymous hero, having become narcissistic, feels guilty of cruelty, for he has rejected his mother, who is now a lone beggarwoman who has pleaded with him to come back to her. In the second act, he has recognized through dreams, that in the making of his magnificent coronation robes, poverty-stricken slaves have died (“given their lives” is the euphemism). He subsequently chooses to go to his coronation in rags, to the shame of everyone, the public alike. The Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis are heard near the end of the final act, as the Young King, arriving for his coronation, in rags, having argued fruitlessly outside the cathedral with the Lord Chamberlain who has tried to dissuade him, storms into the cathedral, only to have a further argument with the Bishop, who sings his reproachful aria “My son, I am an old man, and in the winter of my days”. As the Young King opens the doors of the cathedral, we hear the opening of the Magnificat in full voice.

Pilgrim’s Song (1984) is a setting of John Bunyan’s words from Pilgrim’s Progress which I used in the 2nd act of The Star-Child, which presents the dreams of the Young King, in which slaves’ lives have been sacrificed to make him rich and powerful. The Star-Child, burdened by guilt, and choosing to reject the wealth he is to inherit, becomes a pilgrim as two monks, representing the Star Child’s dreaming soul, sing the poem in searching two-part counterpoint, expressing a sense of searching, while also evoking a sense of humility. I have used John Bunyan’s original words, not Percy Dearmer’s famous and desecrated hymn version, which not only changes words altogether, but confuses 1st and 3rd persons.

Rejoice! Rejoice! (2010) was written for the Jubilee Opera Chorus production of Beatrix Potter’s The Tailor of Gloucester. It was to be sung at the moment Beatrix Potter describes, that in the old story “all the beasts can talk in the night between Christmas Eve and Christmas Day in the morning (though there are very few folk that can hear them, or know what it is that they say)”.

In the Bleak Midwinter (2015) is a setting of Christina Rosetti’s poem first published in January 1872. Without their asking, my setting was written for Seraphim, the amateur female singing group in East Anglia founded by Vetta Wise. In choosing a text, I thought it would be nice to set Christina Rosetti’s words, one of which is the gentle word: Seraphim. Because there was no prospect of Seraphim performing the work, I chose to allow myself intervals difficult for amateurs to sing. But, the members of Seraphim were very brave, and liking the music in rehearsal, were determined to sing it. They performed it in 2017 with flute (Anna Noakes) and harp (Gabriella Dall’Olio) helping them. There is no doubt that the piece should be sung unaccompanied as it is in this recording. There are two poems on this CD album which are more famous as hymns or carols, with tunes designed to comfort the listener. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Song better known as the cheerful hymn He Who Would Valiant Be. The other is In the Bleak Midwinter made famous in the deeply comforting musical settings by both Gustav Holst and Harold Darke. In the cases of both poems, I wanted to find a more challenging and poignant meaning in the words than the famous tunes would suggest. In Christina Rosetti’s carol I was keen to set the freezing words “snow on snow” in such a way that they would express bleakness and coldness. Britten had done just this in his setting of In the Bleak Midwinter within his choral work, A Boy is Born. Perhaps regretfully, I used a version of the poem found in a traditional anthology. Sadly, and primly, the anthology left out the beautiful verse about ‘a breastful of milk’. I have found it impossible, in retrospect, to insert a new setting of the verse, as the structure of the musical journey can only be damaged by doing so.

Blessèd is the Man who Finds Wisdom (2015) (words from Proverbs chapter 3: verses 13-18) was written for Maggie Beale in memory of her husband John, to be sung by the Orford Benefice Choir (of which he was a member). Maggie chose various possible words to set to music, including some by Shelley, but we settled on these. In reply to a solo female phrase, the anthem finishes with a tenor solo voice, representing John, for he was a tenor in the choir, and he may be said to have the last word, surrounded by a choir of angels.

For Behold, I Create New Heavens and a New Earth (2019) was written for Graeme Kay and the Orford Benefice Choir, who performed it on the occasion of the Easter 2019 dedication of the newly acquired Peter Collins organ. To date, it is the only piece specifically written for that instrument since it came from Southampton to take its place in Orford. It is a setting of Isaiah 65: verses 17-25. Having discovered that the biblical reading for the day of performance was Isaiah 65: verses 17-25, I was immediately inspired by the interesting words, and I set them to music very quickly and confidently. I was already familiar with the literary style and prophetic voice of Isaiah, as in 1999 I had set words from Isaiah 35 in my piece, Isaiah 35: Three Advent Carols. I am very pleased with my liberal choice of keys and modulations in this work. I enjoyed briefly quoting Britten’s Old Abram Brown at one point. I have discussed tonality and modulation elsewhere in this booklet, as it is a fascinating and important subject.

Good Friday Music (Seven Last Words) (2015) was written for liturgical use, to enhance Good Friday services, and vigils, by the use of thoughtful and contemplative music and silences. I was somewhat impatient with the lack of these qualities in a Good Friday service I had recently experienced, when the string quartet which performed Haydn’s Seven Last Words received applause from the congregation. The focus was on the activity of the musicians, and English politeness was observed. The spirit and poignancy of the occasion should have invoked silence. Words can be so beautiful when given focus of mind and thoughtful expression; and so, the music throughout the composition develops not at all, because the important thing is how the words turn to silence, and meditation. The music is full of phrases which become familiar by repetition and recognition. And then there are passages completely free from leitmotifs, such as the setting of “Greater love hath no man than this: That a man lay down his life for his friends” which was originally written for a Taizé service in a church local to me; as there seemed to be no existing Taizé chant for those words. In my setting, I took no trouble to find different music for the words “This is my commandment: That ye love one another, as I have loved you” as I was specifically avoiding development. In my setting – after the final words “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life” I wrote a final, paused, bar of silence and the indication that “This bar is everlasting peace; the congregation leaves in silent contemplation”.

A note about the composer

I was brought up with the music that my father loved: Mozart and Beethoven (piano concertos, symphonies, sonatas and Mozart’s operas). I feel content that music with such classical grace and structure was my musical upbringing. My father would have scorned with amusement the emotionalism of music such as Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Piano Concerto, and I did not know that piece until I was 20 years old. He liked records of some popular music such as Tom Hark, Rock around the Clock, and songs sung by Burl Ives, all of which I adored. I knew almost nothing about the popular music of the fifties and sixties. At the age of 15 or 16, I was admonished at one family Christmas party, while playing Christmas Carols, for not knowing White Christmas; although, at the age of 13, I had been introduced by fellow pupil at school, Timothy Lowe, to American musicals: My Fair Lady, Gigi, and many of the great Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals. My life was transformed by these joyful things, until a year later when I became enthralled with the Beatles and Procol Harum. After leaving school at the age of 16, I discovered Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle and also immersed myself in the music of Mahler, who was at that time not yet widely performed. After three years at the Yehudi Menuhin School of not having listened enthusiastically to classical music, I heard a broadcast of Mozart’s Mass in C minor. The soprano solo’s scale upwards and downwards in the Kyrie overwhelmed me, and I was given back to Mozart again.

Tonality and Modulation

Tonality and Modulation seem to me to be among the most magical discoveries in the world of music. Atonality may be a different art-form, altogether, from tonality. Tonal keys are like colours. In For Behold, I Create New Heavens and a New Earth the key of A major may be joyful-and-sunny, E flat major warm-and-sunny, C sharp major distressing, G sharp minor miserable, F sharp minor reflective, the final transition to F sharp major comforting. Notes may be like people. There must be enough consonance for the community to co-operate. Dissonances should be resolved. A preponderance of dissonance is anarchy. In tonal music it can be shockingly clear when a wrong note is played, and certain harmonies can shock by their unexpectedness. Harrison Birtwistle has said “I wonder whether I have ever written a note which might not be better replaced by another”. His tonal world was one where all notes were equal. Tonality causes us to care about hierarchies amongst notes, and gravitational pull. Perhaps we have not yet discovered whether equality is for the better or worse. I think it is possible that tonality represents human feeling, and that atonality represents God’s impartiality. Boulez said “History seems more than ever to me a great burden. In my opinion we must get rid of it once and for all”, and the statement is very interesting, and one I might have sympathy with. But by attempting to get rid of history, Boulez made history, with himself as one of its leaders, more than anything – causing great distress for those like me who wished to embrace history, and yet remain evolutionary rather than revolutionary. For Boulez also said “No composer is worth taking seriously if he does not use serial technique”, – which only makes good sense if “serial” is taken to mean what Peter Maxwell Davies meant when he said to me that “a composer should use every ounce of technique he has”. Beethoven, Haydn and Mozart were not serial; but they had technique.