Artist Led, Creatively Driven

George Lepauw

Diabelli Variations

Release Date: October 27th

ORC100266

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

33 Variations on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op.120

1. Thema – Vivace

2. Variation I – Alla Marcia maestoso

3. Variation II – Poco allegro

4. Variation III – L’istesso tempo

5. Variation IV – Un poco più vivace

6. Variation V – Allegro vivace

7. Variation VI – Allegro ma non troppo e serioso

8. Variation VII – Un poco più allegro

9. Variation VIII – Poco vivace

10. Variation IX – Allegro pesante e risoluto

11. Variation X – Presto

12. Variation XI – Allegretto

13. Variation XII – Un poco più moto

14. Variation XIII – Vivace

15. Variation XIV – Grave e maestoso

16. Variation XV – Presto scherzando

17. Variation XVI & Variation XVII – Allegro

18. Variation XVIII – Poco moderato

19. Variation XIX – Presto

20. Variation XX – Andante

21. Variation XXI – Allegro con brio

22. Variation XXII – Allegro molto alla “Notte e giorno faticar” di Mozart

23. Variation XXIII – Allegro assai

24. Variation XXIV – Fughetta, Andante

25. Variation XXV – Allegro

26. Variation XXVI – Piacevole

27. Variation XXVII – Vivace

28. Variation XXVIII – Allegro

29. Variation XXIX – Adagio ma non troppo

30. Variation XXX – Andante, sempre cantabile

31. Variation XXXI – Largo molto – espressivo

32. Variation XXXII – Fuga, Allegro

33. Variation XXXIII – Tempo di Minuetto moderato

George Lepauw, piano

The Diabelli Variations

Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations are considered to be amongst the greatest masterpieces ever written for keyboard. Often compared to Bach’s Goldberg Variations, they go in fact further, opening up entirely new worlds of musical expression, artistic creativity, and harmonic and rhythmic invention. They also represent, in a kaleidoscopic yet concise form, an abstract of Beethoven’s entire musical thought.

Dr. Julia Ronge, Beethoven scholar and curator of the Beethoven-Haus archives and manuscript collection in Bonn, calls the variation form “Beethoven’s superpower”. Indeed, it is true the variation form suited Beethoven’s temperament perfectly. It was in fact a set of variations on a march by Ernst Christoph Dressler that launched the budding composer with his first published work. Written when Beethoven was just eleven years old during the year 1782, these variations on a march of no particular interest by an insignificant composer who is entirely forgotten today in some ways foreshadows his last variation set, on a commonplace waltz by Anton Diabelli (1781- 1858), a composer and music publisher who would be nearly forgotten today were it not for his association with Beethoven.

The variation form accompanied Beethoven throughout his life, as he frequently used popular tunes of his day (and even England’s “God Save the King”) to show off his rife musical ideas. In addition to his formally published variation sets on other composers’ music, he also composed original themes of his own, most famously for the Eroica Variations, Opus. 35. But variation form was more than just a composer’s intellectual exercise; it was also, and perhaps primarily in the first instance, a pianist’s showcase. Indeed, Beethoven first rose to fame as a performer, virtuoso and improviser of unequalled genius, and it was common in his time to show off one’s talent by improvising on given tunes during performances, as well as to battle other virtuosi in musical duels by showcasing one’s ability to improvise on any popular air of the day. In these instances, Beethoven always came out the acclaimed winner.

Beethoven’s variations on Diabelli’s waltz were not, however, composed with the idea of performing them himself. By the time of their publication in 1823 (just one year before the glorious premiere of his Ninth Symphony) Beethoven had not performed in public for nearly a decade and was pretty much entirely deaf. Rather, these variations were a way for Beethoven to experiment in the world of pure ideation, as he might have at the piano while improvising, but on paper only. This does not make them in any way less virtuosic, or less physical and more abstract, as any pianist who has been confronted to them knows!

Similarly to the art of improvisation, variation allowed Beethoven to set aside the usual formalities and grand dramatic arc of the sonata form, which he used throughout his career in instrumental sonatas, chamber works, or symphonies. Variations allowed for greater freedom and could go in any direction without limitation of pieces. In the Diabelli case, Beethoven composed an impressive thirty-three variations, but he could as well have stopped as twenty-three or forty- three. So why thirty-three? Some have posited that it was one more than his set of thirty-two variations on an original theme in c minor (Beethoven did like to surpass himself), and others have thought instead that it was competitively intended to surpass Bach’s thirty Goldberg Variations. Most probably he must simply have felt that he had explored all worthwhile aspects of the theme. Yet, however short each average variation is, many under two minutes, as a whole this work remains the longest he ever wrote for piano.

Anton Diabelli, a well-versed and honorably-skilled musician and composer, launched a music publishing firm in 1817. In 1819, he decided to ask the most famous musicians of Austria to compose a single variation on a theme he had composed for the occasion, to form the basis for a compilation which he would publish and sell to raise funds for the widows and orphans of soldiers killed during the recently-ended Napoleonic Wars. Fifty well-known composers of this period responded favorably to this request, including Franz Schubert, Carl Czerny and his eleven-year old student Franz Liszt, Mozart’s son Wolfgang Amadeus fils, Ignaz Moscheles, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and even the Archduke Rudolph, who was Beethoven’s student and a good musician in his own right. Beethoven, however, initially turned down the request (not because he was against charity work, which he himself contributed to multiple times) because he considered Diabelli’s Waltz to be of no interest, and had other big projects on his mind.

The waltz, probably left upon his desk, entered Beethoven’s inner ear like a worm. Contrary to his initial impression, he ended up finding Diabelli’s tune of utmost interest and began to experiment with it. It took him just a few weeks to compose twenty-three variations! He thus negotiated a personalized contract with Diabelli, who agreed to Beethoven’s condition to publish his set of variations in a separate volume and pay him a handsome sum for the forthcoming master opus. As was often the case, Beethoven did not complete the volume as quickly as he had started it, setting it aside for three whole years. It was at that time he began work on his Missa Solemnis, his last three piano sonatas (opus 109, 110 and 111) and the Ninth Symphony. Only after all but the Ninth had been completed did he come back to Diabelli’s theme to compose ten more variations. He presented the completed set of thirty-three Variations to Diabelli in the Spring of 1823, and the first edition was printed shortly thereafter.

Much ink has been spilled on this work, and this recording’s presentation is not the place for an in-depth analysis of this composition. However, it is to be noted that the title Beethoven used in the original German was “33 Veränderungen über einen Walzer von Anton Diabelli”, which is more accurately translated as “33 transformations on a Waltz by Diabelli” rather than the commonly used term “Variations”. This is an interesting point to mention considering that Beethoven took the original thematic material so far beyond its original statement that it becomes sometimes very difficult to recognize its inspiration in the variations it supposedly gives birth to. Rather than creating variations on a theme, Beethoven went toward a full metamorphosis and deconstruction of this theme, taking it apart, isolating melodic patterns, intervals, rhythms, tempi, and even playing with dynamics and registers prescient of techniques birthed by the Second Viennese School of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg.

Beethoven tears Diabelli’s theme apart, reconstructs it, cajoles it, tortures it, twists and turns it around. Diabelli’s Waltz first becomes a March, then a tip-toed middle- of-the-night excursion, before finding its first moment of sweet repose. Later, it becomes frantic, then deranged, and gets knocked-about in unfathomable ways, somehow reminiscent of honky-tonk like in Variation XVI. Beethoven has fun and pokes fun, shows off his devilish virtuosity, his ability to speed up and slow down, of proclaiming loudly and also of whispering inaudibly. He proves his capacity to equal Bach and Handel in his fugues and Mozart in his closing, celestial minuet. If we were not aware of historical chronologies, we would even say he found inspiration in Chopin and Brahms, and maybe even in Debussy!

Through it all, Beethoven seeks total expressive freedom, in a constant dialogue with his world and with himself. This work is one of extreme contrasts, and unlike Bach’s Goldberg Variations which can fall into the category of easy listening masterpieces, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations require absolute listening and the full engagement of the listener. Indeed, the joys of this work come to those who let Beethoven take them for the ride, all while remaining fully alert. Beethoven will then show his true colors, from gregarious jokester to the deeply lonely soul he hid within. At the end, he will reaffirm the beauty of life (despite its many hardships) and will give his attentive listeners renewed strength and hope.

With these variations, Beethoven the alchemist will have managed to transform Diabelli’s common waltz into pure gold, just as his very own mythological hero Prometheus brought fire, and thus life as we know it, to humanity.

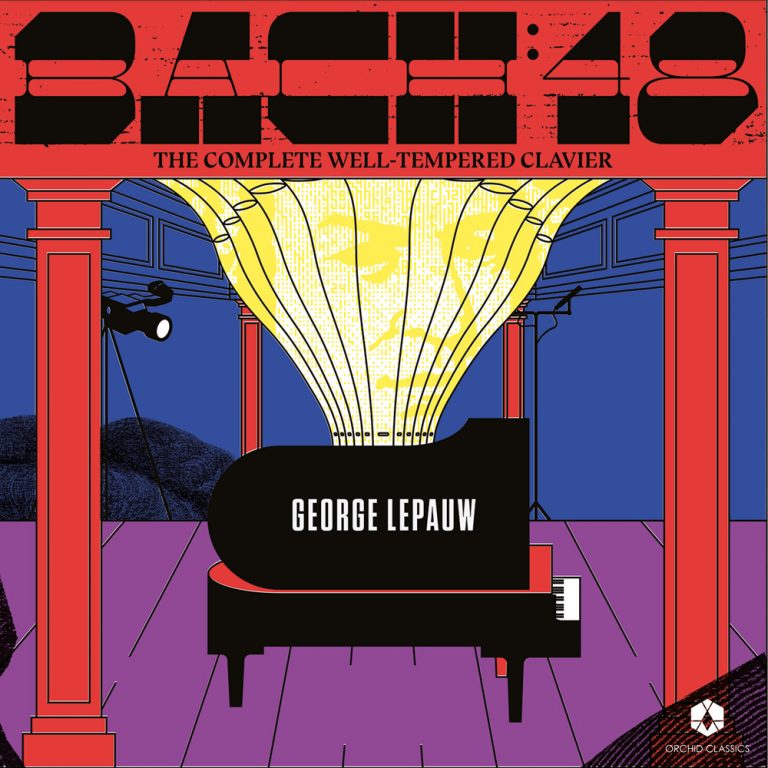

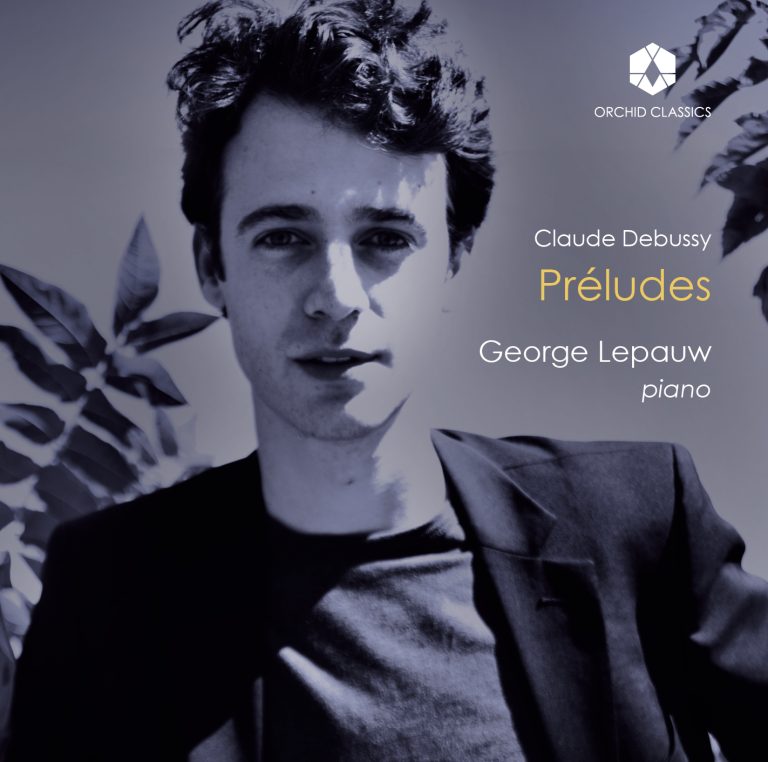

George Lepauw is a Franco-American pianist based in Paris, France with a strong connection to Chicago, Illinois. Recent recordings on Orchid Classics include his Bach48 Album of the complete Well-Tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach, and the complete Préludes for piano of Claude Debussy. He has also released The Beethoven Project Trio, an album of piano trios that includes a Beethoven world-premiere, for Chicago-based Cedille Records. This present recording of the “Diabelli” is the first piano solo Beethoven album of several that George Lepauw will release to mark the bicentenary of the composer’s death in 2027.

George Lepauw’s musical education has included private studies with Aïda Barenboim, Elena Varvarova, Brigitte Engerer, Rena Shereshevskaya, Vladimir Krainev, James Giles, Ursula Oppens and Earl Wild. He has been additionally mentored and supported by Carlo-Maria Giulini, Maria Curcio, Charles Rosen and Kurt Masur.

He holds degrees in History and Literature from Georgetown University and in Piano Performance from Northwestern University.

George Lepauw is also the founder of the International Beethoven Project in Chicago and has been widely recognised for his visionary artistic leadership in music, art and film festival direction.

Concurrently to his performing and recording career, George Lepauw teaches piano privately and in public masterclasses. He also occasionally composes music, produces music films and writes numerous articles on culture and music.

Follow George Lepauw’s musical journey at: www.georgelepauw.com