Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Milo

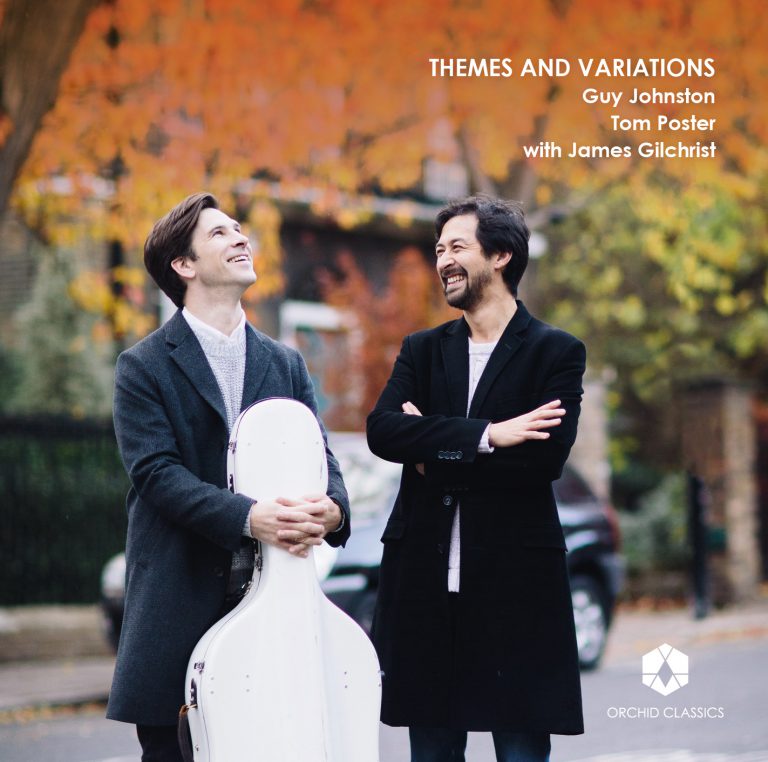

Guy Johnston

Kathryn Stott

Release Date: May 2010

ORC100010

Frank Bridge (1879-1941)

Spring Song (1912)

Melodie (1911)

Cello Sonata, Op. 125 (1913-17)

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Sonata for cello and piano in C major, Op. 65 (1961)

Mark-Anthony Turnage (b.1960)

Sleep On (1992)

Milo (2009)

At the heart of this CD lies a handful of richly productive musical relationships: the first between Frank Bridge and Benjamin Britten; the second between Benjamin Britten and Mstislav Rostropovich; and the third between Guy Johnston and his friend Mark Anthony Turnage.

The music we hear from Frank Bridge predates his friendship with the young Britten, but Britten was an unswerving champion of all of the older man’s music, including that written by the younger Bridge before his style evolved so radically that audiences ceased to want to hear his music. The relationship between Britten and Rostropovich elicited the former’s Cello Sonata; without that relationship, the piece would not have been written. Britten was more often than not inspired to write for a particular performer “ most famously, Peter Pears, of course “ but also for the prodigiously gifted cellist who so captured his imagination, ‘Slava’ Rostropovich.

Britten first encountered Bridge in 1924, when he was only ten, seven years after Bridge had written his Sonata in D minor Op. 125 for Cello and Piano (1917) and even longer since Bridge had produced his Mélodie for Violin and Piano or Cello and Piano (1911) and Spring Song (the second of ‘Short Pieces for Violin & Piano’, nos. 1 & 2 of which were also published for cello) (1912).

Bridge’s musical training was embedded in the Germanic tradition imparted by his teacher, C.V. Stanford, at the Royal College of Music. Bridge had spent three years at the RCM studying violin and piano before gaining a scholarship to spend a further four as a composition student. His style then was described by Britten in 1948 as that of one ‘brought up in German orthodoxy, but who loved French romanticism and conception of sound “ Brahms happily tempered with Fauré’. Bridge’s background as a string player (which he shared with his wife Ethel, whom he met in the violin section of the RCM orchestra) resulted in many of the works styled later, somewhat disparagingly, as ‘salon music’, into which category the Spring Song and Mélodie fall. He was described by Eric Coates as ‘sympathetic, kind, helpful, understanding, an artist to his fingertips and generous in his praise of others’ and Josef Holbrooke described Bridge as ‘the figure of happiness in British music. His gifts are as natural as Schubert’s; his melody and harmonic invention is of the charming order. He has not delved, or procrastinated in his work because of the latest chords found by the pushing adventurers from abroad. He does not befog the listener with a rhodamantade of noise or affectedness. One can enjoy his gift in song, in chamber music and orchestra without the qualms which usually beset us when we listen to the modern composer. …Melody is there from Bridge in abundance, and no one can write better for chamber music than he’.

The effect of the First World War on British composers is often considered only in terms of the obvious effect on those young composers who, like Gurney and Vaughan Williams, fought in it or who, like W. Denis Browne and Butterworth, lost their lives in it. The effect of the War on the older, more established composers who stayed at home was in some cases also profound. Elgar was precipitated into cynicism and despair. Like many of his younger contemporaries, he blamed the conflict on the pre-war world. In a letter of 1917 he wrote ‘I cannot do any real work with the awful shadow over us… Everything good & nice & clean & fresh & sweet is far away – never to return.’ It is not surprising, therefore, that Elgar’s Cello Concerto, written after the War, is so very different from his Violin Concerto of 1910.

Bridge was similarly affected. The pianist Ada May Thomas is reported as recalling that ‘during the First World War, when he was writing the slow movement, he was in utter despair over the futility of war and the state of the world generally, and would walk around Kensington in the early hours of the morning unable to get any rest or sleep’ . The state of mind induced by the War resulted in a radical transformation in Bridge’s music. The salon music writer who had produced accessible, well-loved works started to write more challenging music, with a new harmonic language and with freer forms. English audiences were not impressed and his music gradually ceased to be performed.

Today Bridge suffers from the fact that he is still known for his early ‘salon music’, which is disparaged and so rarely performed, and for the fact that he was effectively silenced once his style had changed, with the result that his later music is largely unknown. In the Aldeburgh Festival Programme Book of 1965, Benjamin Britten wrote a perceptive account of Bridge’s stylistic development: ‘Frank Bridge is known almost entirely by his early works, those written before the first world war; such as the Sextet for Strings, the Piano Quartet-Phantasy, the first two quartets, the Suite ‘The Sea’, and the many and lovely songs. To those who know only this period of his work the later pieces must seem like those of another composer. The earlier works are tonal, and harmonically direct; the melodies clear and strong; the rhythms if not square, then rather regular. The later works have no clear keys, are acid in harmony, the melodies have a curious conversation-like character, and the rhythms are usually irregular, and definite rhythmic patterns are rare. But to one more familiar with all his works the connection between the two periods is clear – the seed of the later works is in the earlier; … the later works are an evolution from the earlier – stemming from a desire to say more personal and subtler things. They can be difficult at first to follow, apart of course from the invariable fascination of the sound; the conversational melodies can be difficult to recognise, but the moods are clear, and the drama and tensions easy to feel’.

Bridge’s Sonata for Cello and Piano (1913-7) was the last major piece he wrote until the Piano Sonata (1922-5) and shows how much Bridge was opening himself up to new influences and attempting, as Britten observed, to articulate ‘more personal and subtler things’.

When Britten, aged 10, first encountered Bridge’s music at the Norwich Triennial Festival of 1924 it was a pre-War work of 1910-11, that he heard. As Britten later recalled: ‘I heard Frank Bridge conduct his suite The Sea and was knocked sideways. My viola teacher was an old friend of Bridge’s and when the success of The Sea brought him to Norwich again in 1927, I was taken to meet him; we got on splendidly and I spent the next morning with him going over some of my music; he had no other pupils, yet he knew that he had to present something very firm for this stiff, naive little boy to react about’.

Britten’s lessons with Bridge were hard ones. Bridge seemed to forget at times that he was dealing with a young boy. ‘I used to get sent to the other side of the room; Bridge would play what I’d written and demand if it was what I really meant. I’d retort yes it was. And he’d grunt back, “well it oughtn’t to be”.’

Bridge’s generosity to his young apprentice was reminiscent of Haydn’s towards the young Mozart, for in each case the older man recognised genius in a youth. But the master-pupil association in this case went beyond music; Britten was like a substitute son to the childless Bridge and his wife; the two shared many things, including a love of the countryside, tennis, and, most importantly, a belief in pacifism. ‘A lot of my feeling about War’, said Britten, ‘came from Bridge. He’d written a piano sonata in memory of a friend killed in France; and although he didn’t encourage me to take a stand for the sake of a stand, he did make me argue and argue and argue.’

In fact, the only thing the two men disagreed upon was the music of Mahler (Britten for, Bridge against). They stayed close after Britten went to Bridge’s alma mater, the Royal College of Music. Britten dedicated the first piece which he deemed worthy of an opus number, his Sinfonietta, to Bridge, and at the end of 1937 he wrote Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, an affectionate tribute to his mentor, with headings to each section denoting Bridge’s personality: (‘His Energy’, ‘His Charm’, ‘His Humour’, ‘His Skill’ etc..) Bridge in his letter of thanks wrote ‘It is one of the few lovely things that has ever happened to me’.

When Britten and Pears left for America in 1939, the Bridges turned up at Southampton to see them off. Bridge gave his viola to Britten as a parting gift. The two were never to meet again. Bridge died two years later.

Guy Johnston’s first experience of the music of Benjamin Britten was as a chorister at King’s College, Cambridge. There he sang the Hymn to St Cecilia and A Ceremony of Carols, amongst other Britten works. This experience of Britten’s choral compositions was an excellent introduction for an instrumentalist, because it was to the human voice that Britten most naturally gravitated. In an interview of 1961 Britten said: ‘I know that my inclination is to start from the vocal point of view – that has been for many years now. But on the other hand when a performer like Slava Rostropovich comes along, who excites me – I’ve found that I wrote a cello sonata for him with a great deal of ease, and a great deal of pleasure… In fact I am now planning a cello concerto for this wonderful Russian cellist, as well as of course other vocal works’.

In 1964 he reiterated this preference for the voice, again referring to Rostropovich as the agent who unlocked his creative energies when it came to writing for an orchestral instrument: ‘Nowadays I don’t seem to lose confidence in writing vocal music, but I think I was getting a bit nervous about instrumental music. Rostropovich freed one of my inhibitions. He’s such a gloriously uninhibited musician himself, with this enormous feeling of generosity you get from the best Russian players, coming to meet you all the way. I’d heard about him, and rather unwillingly listened on the wireless. I immediately realized this was a new way of playing the cello, in fact almost a new, vital way of playing music. I made arrangements to come to London and heard him again, and found him in the flesh even more than I’d expected. He took the bull by the horns and asked me to write a piece for him, which was my cello sonata written “on condition he came to Aldeburgh!”‘

Britten’s first encounter with Mstislav Rostropovich was courtesy of Shostakovich in September 1960, who introduced the two men in London after a performance of his (Shostakovich’s) Cello Concerto (the piece, incidentally, with which Guy Johnston won the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition in 2000). Rostropovich recalling the encounter, admitting that up until that point he had assumed Britten was a ‘dead composer’. Linguistically, it was a challenging relationship, since Rostropovich’s only English expressions were ‘goodbye’ and ‘thank you very much’. The cellist did, however, manage to make clear his wish that Britten write him a cello sonata. A few days later Rostropovich wrote to Britten: ‘Thank you for this from the bottom of my heart. Not for a second do I doubt the success of this venture… From now on, all my life is expectation of your new composition… I am taking with me from England many recordings of your music (including Noye’s Fludde)…’

The reference to Noye’s Fludde is interesting, and one cannot help wondering whether this is what prompted Britten, consciously or otherwise, to open the new sonata with material which is reminiscent of the sequence for flute depicting the flight of the dove in his opera for children. By January 1961 he had all but finished the work: ‘As far as I can I’ve got the cello piece in order, at least I must stop fiddling with it & get on with something else. I played it to Imo [Imogen Holst] who was quite impressed, &, as if an omen, as soon as I’d played it over, the telephone rang & there was ‘Slava’ [Rostropovich] from Paris, & I had a wild & dotty conversation in broken German ( very broken) with him. But he is a dear, & his warmth & excitement came over of the bad line & crazy language’.

Rostropovich received his Sonata in February, accompanied by a note from Britten expressing the hope that ‘you can make something of it’, saying that he thought the pizzicato movement would ‘amuse’ the cellist, and adding that ‘I hope it’s possible!’ Rostropovich telegrammed back: ‘ADMIRING AND IN LOVE WITH YOUR GREAT SONATA…. LOVEÂ ROSTROPOVICH’.

When in March the two men again met in London, both were overwhelmed with nerves. It was only after several drinks (Rostropovich later recalled ‘whisky’ and then ‘a little bit whisky more’), that they were able to surmount their anxieties and play the piece through. Afterwards, at a restaurant, Rostropovich noticed Britten repeatedly humming the same glissando phrase. ‘I realised’, he said, ‘that Ben was tactfully teaching me how to play this phrase…. I captured the spirit of this theme by imitating the way he had hummed it. Ben would never give explicit instructions… I had to learn to grasp at hints like this.’ Thus with humming, whisky, and the bowdlerised German that was later to become known as ‘Aldeburgh Deutsch’, one of the most creative musical relationships of modern times was born. The work was premiered to great acclaim at that summer’s Aldeburgh Festival, and Britten went on to write the Symphony for Cello and Orchestra (1963) and the three Cello Suites of (1964, ’67 and ’71) for Rostropovich.

Guy Johnston first heard the Bridge Sonata when, aged 16, he was studying in the USA. Someone handed him a recording of Steven Doane playing the piece, and that, says Guy, ‘grabbed me and I wanted to go and study with him’. He learned the Britten Sonata while studying with Doane and this early experience of the piece is overlaid with Guy’s own experiences of Aldeburgh, where he has held residencies which have afforded him the opportunity to look at a lot of the correspondence between Britten and Rostropovich and to study the original manuscripts. ‘Through the residencies’, Guy explains, ‘you can get as close as you can to the origins of this music… there is definitely a spirit there. I did a lot of my early training for the London Marathon there, whilst I was learning the First Suite – running up and down the coast towards Southwold .’ Guy had first-hand experience of Rostropovich himself when, as a member of the National Youth Orchestra, the great man came to conductThe Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra and Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 10. ‘Such a momentous occasion’, Guy recalls, ‘his presence and everything about him was so exciting’.

For any tenor who sings Britten’s music, there is a legacy to address, left by the person for whom the music was originally written. Memories of Peter Pears’ distinctive performances of music tailor-made for himself present a challenge for any tenor stepping into his shoes. Likewise a cellist has to deal with the fact that this repertoire was written for a specific performer whose personality is stamped all over it. Britten’s own description of the last movement of his Cello Sonata in his sleeve note to the original Decca recording, which speaks of the frequently changing character of the music, ‘now high and expressive, now low and grumbling, now gay and carefree’, captures the personality of the man for whom it was written. (Rostropovich himself described this movement as ‘irresponsible and tempestuous’.)

As Guy Johnston points out, ‘a lot of the technical aspects of the work, like the pizzicato movement, the harmonics and some of the sound effects “ and just being bold enough to try things out “ are Britten’s response to the exciting possibilities of writing for Slava. The last movement resonates with the Shostakovich Cello Concerto, because of the intervals. It strikes me as a player of both pieces that Britten definitely had Russia in mind, as well as the artist“ and the circumstances in which he had originally met him’.

But Guy adds, ‘As a musician you have all these recordings resonating in your ears as you are growing up, but at the end of the day Britten wanted to continue having his music played. You have to accept the music for its own sake, as Britten intended, without reading too much into it’.

Guy’s residencies at Aldeburgh brought him ‘as close as you can get’ to the world of Britten and Rostropovich. Getting near to the world of Mark-Anthony Turnage is a much simpler matter, since Mark and his wife Gabi, who is also a cellist, are old friends of his. Mark wrote his first piece for cello, Sleep On, for Alexander Baillie, who premiered it in the early 1990s. Mark describes it as ‘ a lullaby, composed before I had my children, who have often since been the spur of my lullabies’. Fatherhood inspired the composition of the gentle, lyrical little piece, Milo. As Mark explains, ‘the births of my children make me feel very creative’. It was written for the christening of Mark’s son, Milo, and premiered at the service in Thaxted Church by Milo’s godfather, Guy Johnston.

©Emma Disley 2010

‘…gripping performance.’ (The New York Times)

‘…real sensitivity.’ (The Observer)

‘…Something more than music went into the making of this album.’ CD of the Week, Norman Lebrecht)