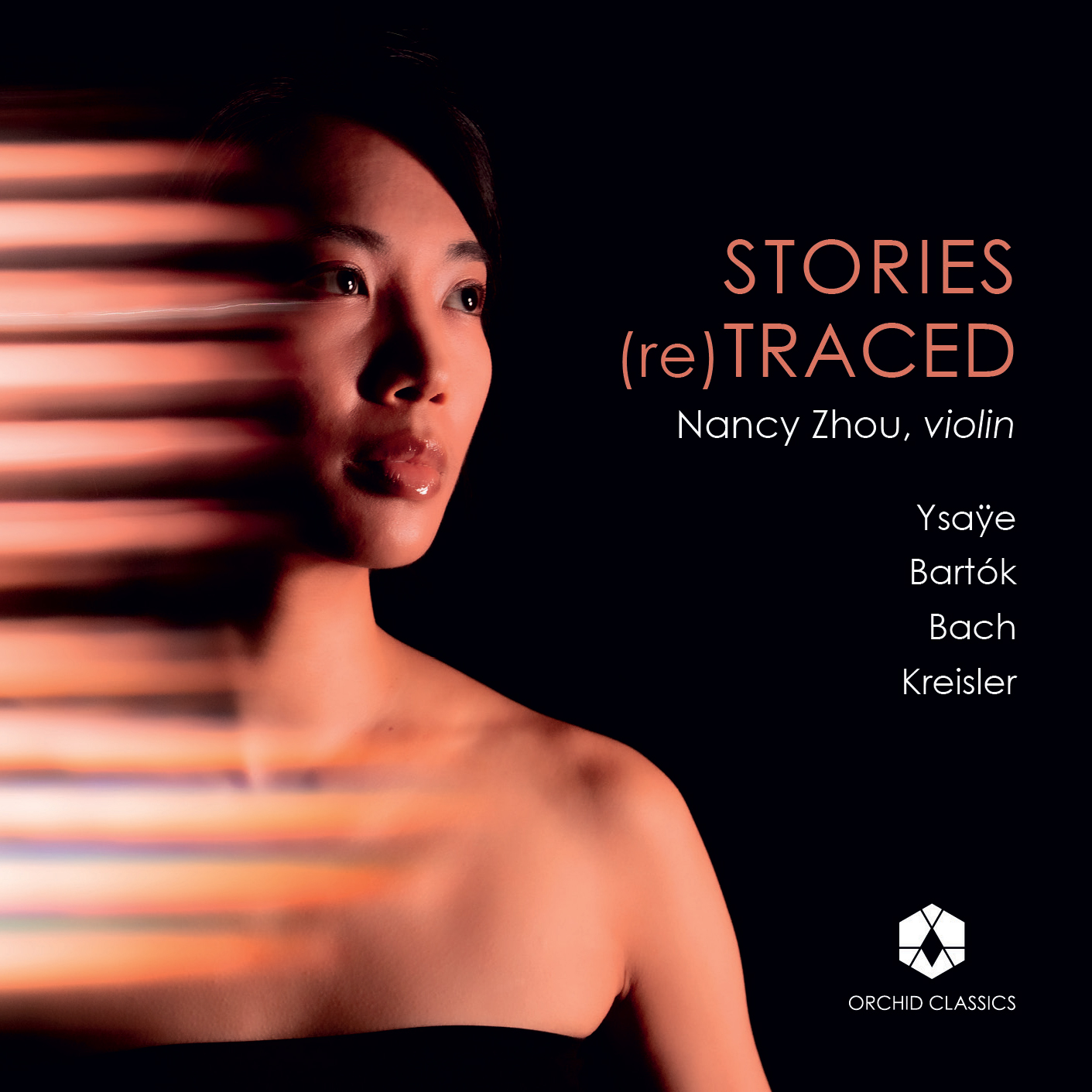

Acclaimed violinist Nancy Zhou presents her own personal exploration of the essence of the human experience through four masterful composers: Bach, Bartók, Ysaÿe, and Kreisler.

STORIES (re)TRACED

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931)

Sonata No.4 in E minor, Op.27/4

1. I Allemanda. Lento maestoso

2. II Sarabande. Quasi lento

3. III Finale. Presto ma non troppo

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Sonata for Solo Violin, Sz. 117

4. I Tempo di ciaccona

5. II Fuga

6. III Melodia

7. IV Presto

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Partita No.1 in B minor, BWV 1002

8. I Allemande

9. II Double

10. III Courante

11. IV Double

12 V Sarabande

13. VI Double

14. VII Tempo di Borea

15. VIII Double

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

16 Recitativo and Scherzo-Caprice, Op.6

Nancy Zhou, violin

What does it mean to be human? A hackneyed question, yes, but one that still to this day welcomes a potpourri of responses, weaving themselves into an unfinished tapestry of the human condition. This album is one such personal response. It glimpses into the distinct yet interlinked stories of four composers, whose musical personalities are conveyed through four beloved works from the violin repertoire and have profoundly inspired me to address this question.

In the most intimate and vulnerable corners of my imagination, I’ve sought help from each of these personalities: “Bach, father of divine music, master of counterpoint and synthesizer of musical styles and forms, how do you steer a conversation between disparate thoughts towards a sublime state of harmony, away from superfluous conflict? Bartók, folk music alchemist, can you share with us what you’ve learned from the peasant folk of the East, far removed from modern, manicured society, and how you straddle the eccentric and visceral expression of their musical language and the Western tradition of compositional techniques? And, Ysaÿe and Kreisler, colorists and purveyors of beauty, please share with us how your friendship came to be and what lyricism means to you?”

I found open-ended answers and am content to leave them open-ended. Under the guidance of the scores of their works, this quartet of composers helped me retrace and deconstruct the steps in their creative process, and along the journey, trace my own creative path forward – towards the vast terrain of empathy, connection, and all-encompassing expression. Within the music of this album, I invite you to find your own creative answers.

Nancy

_______________________________________________

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931) – Sonata No.4 in E minor, “Fritz Kreisler” (1923) Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) – Recitativo & Scherzo-Caprice, Op.6 (1911)

Two close friends, two luminary violinists, and two works to commemorate the violin as an instrument of lyricism and poetry. Musical gifts the composers dedicated to each other, Ysaye’s fourth sonata and Kreisler’s Recitativo & Scherzo-Caprice are gems the pantheon hailing from the “Golden Age” of violin playing bequeathed to future generations of violinists. When I first learned of the storied friendship Ysaÿe and Kreisler enjoyed in the context of Great War times, I was incredibly heart-warmed; there is no doubt that both titans were in a league of their own, yet the strength of their admiration for each other eclipsed any possibility of egos clashing.

Known as the first modern violinist who introduced wide-ranging, continuous vibrato and articulate bow technique as indispensable expressive devices, Eugène Ysaÿe as a composer added an entirely new dimension to the sung and spoken modes of violin playing. Sketched within twenty-four hours after attending a 1923 performance dedicated to Bach by the Hungarian violinist Josef Szigeti, his six sonatas are cornerstones of the solo violin repertoire that are at once autobiographical and narratorial, aware and ahead of its time. Of the six, the fourth sonata has immediacy and structural clarity in its expression, poignantly yet humorously nodding to an endearing ruse that its dedicatee, Fritz Kreisler, often used to charm his audience. Kreisler loved performing “lost classics” written by significant Baroque composers; little did the audience know that they were composed by the violinist himself. In this spirit, one can say that the fourth sonata is a spoof of a spoof of the Baroque style. While the listener takes pleasure in Viennese folk elements, allusions to Kreislerian mannerisms, and familiar Allemanda and Sarabande dance forms, the performer takes delight in inhabiting the physical and poetic world of the composer/violinist, exploring and attempting his suggested system of fingerings and bowings.

Twelve years before, Ysaÿe’s younger contemporary Fritz Kreisler transcribed his great admiration for his senior in the form of two works, one of which is the Recitativo & Scherzo-Caprice, a two-part piece instantly recognizable as the master’s own and perfect as an encore. The Recitativo persuades and underscores the art of rhetoric with the signature coloristic warmth of Kreisler’s tone, and the off- the-cuff brilliance of the Scherzo makes for a delightful closure. For twelve years this work has accompanied me; I dare say it is a time-withstanding curtsy to music’s life-affrming capabilities.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945) – Sonata for Solo Violin Sz.117, BB 124 (1944)

“…[it] is most varied and perfect in its forms. Its expressive power is amazing, and at the same time it is devoid of all sentimentality and superfluous ornaments. It is simple, sometimes primitive, but never silly.”

And so, driven by his own thoughts on folk – or more accurately – peasant music, Béla Bartók, the man sitting at the helm of ethnomusicology, composed a formidable solo sonata for violin. It was commissioned by the violinist Yehudi Menuhin during the final stage of his artistic life, described as “Synthesis of East and West”. But there’s more to it than mere synthesis. In this last stage of artistic development in his life, Bartók was uncompromisingly intent on not only synthesizing the language of East European musical folklore with art-music techniques derived from West European composers, but also integrating these disparate influences in a continuum of creativity that looks to the past and present for a way forward. What resulted was an output that was both simple and complexly strange, immediate and otherworldly, savage and lapidary, and above all, visionary and fundamental to human nature.

It is all the more tribute to Bartók that his music defies a simple description of “easy” or “beautiful” – at times it is unnerving for the performer and addictively unsettling for the listener. As a violinist, my first encounter with his music was no exception. As a listener, it was rather captivation upon first listen. My gateway into his sound world was his penultimate string quartet no. 5. Striking, banging rhythmic motifs coupled with sometimes murmuring, sometimes sinuous melodies that haunt… Bartók’s music stretches the limits of music, allowing listeners to feel seen during turbulent times.

Such is the spirit in which to experience his solo violin sonata, an unforgettable example of Bartók’s synergistic fusing of the peasant folk idiom with art-music elements adopted from the Baroque era. One hears the whole gamut of expressive sound and human emotion, made distinctly coherent and gripping by conventional Western dance and song forms. In the style of a chaconne, the first movement opens with a polyphonic theme of unbridled energy, directly derived from a folk tune and testing the extremities of the instrument. As the theme undergoes various motivic transformations, it is soon apparent that the chaconne form serves as a vehicle for variation, for which Bartók had a natural and learned affinity. This constant of variation not merely is an intellectual pursuit, but also poetically underscores the composer’s self-awareness and undying sensitivity towards his predecessors – one hears quotations from his fifth string quartet and J. S. Bach’s D minor harpsichord concerto (transposed). This ineffable human quality of Bartók is matched only by his refusal to shy away from strife between extremes.

Continuing this spirit is the electrifying fugue, which brings to life four voices interacting with each other in a kaleidoscope of motions and blistering sound effects. In just under four minutes, the composer confronts the performer with a nearly impossible task of tiptoeing between abrasive angularity and nimble grooving – all for the purpose of highlighting the shades of color imparted on this relentless tug-of-war and even battle of wits between these voices. A deafening halt announces the end of the movement, by contrast rendering the entrance of “Melodia” eerily otherworldly. Memories of all previous discordant moments vaporize and form a veil of nature’s mysterious utterances and sounds in the heart of night. The music invites a synesthetic experience. One hears evening mist, sees bird twitters, feels the sounds of nocturnal creatures… a style that underscores Bartók’s reverence for nature and solitude therein: “night music”. The shadowed tail of “Melodia” then merges with the humming opening of the “Presto” finale; one senses a continuous through-line connecting these two movements. Written in rondo form, this finale opens with a refrain abuzz with the sounds of bees and proceeds to make one last statement for the beauty of incongruity. Interspersed between these refrains are recalls of the peasant spirit through upbeat Romanian folk rhythms and haunting melodies. Much to Bartok’s genius, the music ultimately juxtaposes human and non-human elements, celebrating their distinct expression and provoking thought on the in-between. Simply put, it is fantastically epic.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) – Partita No.1 in B minor for Solo Violin, BWV1002 (1720)

Of the six sonatas and partitas Bach wrote for unaccompanied violin, the first partita takes the most delight in exploring the art of variation. It is a deeply private and utopian microcosm of a work set entirely in B minor – a personal favorite key territory commonly understood to be a haven for the solitary, melancholy, and the tender. I use the word “utopian” because of the the work’s perfect symmetry in form, delicate balance between interiority and virtuosity, and excursions into charmingly awkward rhythms and the physical extremities of musical intervals. These aspects form a living, thriving world in and of itself – a perfect microcosm.

Form and variation are at the foreground of this partita, and these, in addition to its stylized dance forms, are what explain my deep affnity for the work. To understand the form, let’s first take a closer look into the meaning(s) of the Italian term “partita”. “Partita” is understood nowadays as a suite, or collection, of conventional dance forms – in this case the Allemande (a leisurely and noble dance of German origin), Corrente (a sprightly, advance-retreat dance of “running” nature), Sarabande (slow and rather Dyonisian), and Bourrée (quick-footed and upbeat). But an older meaning of the term was in use in Bach’s lifetime: a set of variations. There is a feeling, whether of challenging or agreeable nature, in which the entirety or part of each movement are variations of one another. For the player, this poses the challenge of finding unity in differences – may I add, both literally and figuratively.

The partita is a sequence of four stylized dance movements, each followed by a “double” or a shadow movement if you will. Like a shadow, the accompanying “double” traces the outer voices and harmonic outline of the dance movement they vary, but such nuanced details as rhythms, tessitura (the range of voice), and harmonic colors are up for adjustment. In a scheme reminiscent of the sonata da chiesa form (four movements, slow-fast-slow-fast), each dance and double movements are cast in binary form (two halves, each repeated) to allow the player to explore the repeated material with not only a different perspective, but also with more wisdom gained through the passage of time in the first round. The material itself is dense – there are many points of interest to enjoy, whether harmonically, rhythmically, or in voice interaction. That it is questioned, reconsidered, and even endearingly poked fun at (thinking of the closing pair of movements) leads me to perform them with considered spontaneity and buoyancy. As such, this approach paved the way for my choice of physical setup – a transitional bow and adoption of “Baroque tuning”, roughly defined as A=415 Hertz. Oh, the charm of variation.

Entering the tenth year spent on and off with this partita, I still marvel at its symmetry in form and numinous, meditative quality. And then there is the bubbly structural anomaly – the Tempo di Borea, which replaces the standard Gigue dance and closes the work with the intention to uplift the emotional density of the preceding movements. The journey arc is perfectly complete and lends itself well to nuanced appreciation, and if only for its homogeneity in key, both the player and listener reach an endpoint varied or even changed.

Acclaimed violinist Nancy Zhou presents her own personal exploration of the essence of the human experience through four masterful composers: Bach, Bartók, Ysaÿe, and Kreisler.

From Bach’s intricate counterpoint to Bartók’s raw folk intensity, and from Ysaÿe’s breathtaking virtuosity to Kreisler’s lyrical charm, the album is a captivating journey through the soul of the violin. Offering her own fresh perspective on these iconic works, blending historical insight with personal interpretation, Nancy Zhou invites listeners to engage with the music on a profound and intimate level.

A sought-after soloist and chamber musician, Nancy Zhou has performed with leading orchestras worldwide, including the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Munich Symphony, and Hong Kong Philharmonic. Passionate about education and musical exploration, she is a dedicated mentor and a champion of contemporary works, bridging cultural heritage with artistic innovation.

Nancy Zhou

Violin

Known for her probing musical voice and searing virtuosity, Nancy Zhou seeks to invigorate appreciation for the art and science of the violin. Her thoughtful musicianship and robust online presence resonate with a global audience in such a way that brings her on stage with leading orchestras around the world. More than 20 years since her orchestral debut, Nancy has collaborated with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Munich Symphony, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Naples Philharmonic, San Diego Symphony, among others. A passionate soloist who cherishes chamber music collaborations and commits to education, Nancy has performed at festivals including the Verbier Festival, Ravinia Festival, and the Tongyeong Music Festival; she is a regular guest educator at various international summer festivals, holding masterclasses as well as workshops on fundamental training and wellbeing for musicians.

Over the years, the violinist’s interest in cultural heritage and the humanities manifested in a string of notable collaborations. Alongside the New Jersey Symphony and Xian Zhang, she presented Zhao Jiping’s first violin concerto at Alice Tully Hall; gave the US premieres of Unsuk Chin’s “Gran Cadenza” for two violins with Anne-Sophie Mutter; performed Chen Qigang’s “La joie de la souffrance” with the Rogue Valley Symphony; and, in partnership with the La Jolla Symphony, gave the West Coast premiere of Vivian Fung’s Violin Concerto no. 1. In July 2025, Nancy embarks on a research trip with Vivian to Zhexiang, China, the hometown village of the violinist’s mother, who is a former professional folk dancer; the project culminates with a work for violin and electronics that explores the intersection of folk minority culture and music as a socio-cultural force.

Born in Texas to Chinese immigrant parents, Nancy began the violin under the guidance of her father, who hails from a family of traditional musicians. She went on to study with Miriam Fried at the New England Conservatory while pursuing her interest in literature at Harvard University. She is an Associated Artist of the Queen Elisabeth Chapel and Professor of Violin at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Click the button above to download all album assets.