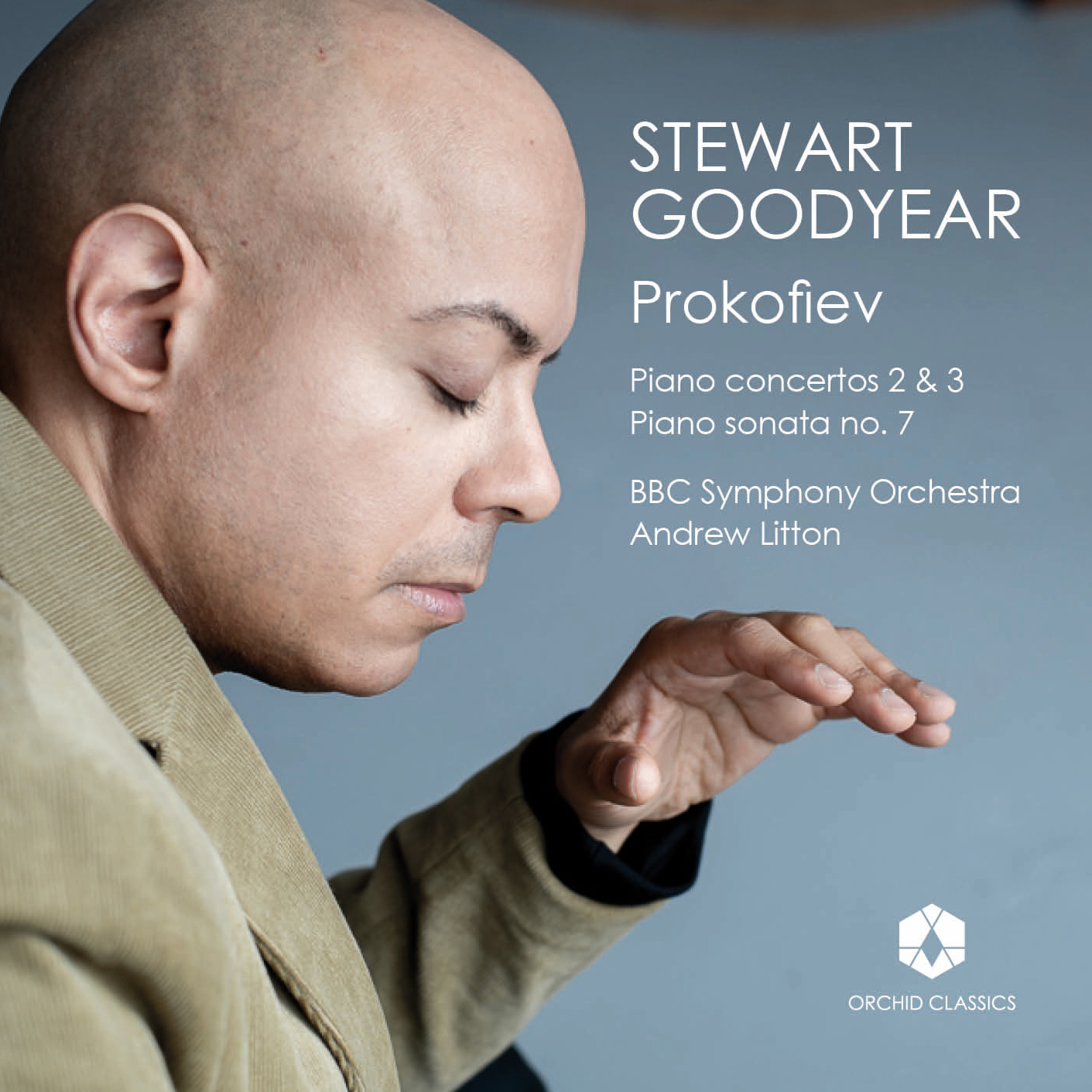

Canadian pianist Stewart Goodyear, in a seminal year which includes his debut at the BBC proms, presents his new album of works by Sergei Prokofiev, alongside the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Andrew Litton. With Goodyear’s sage and seasoned take on these three works, the album takes on another dimension: that of steadfast endurance in the face of personal challenges.

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, Op.16

1. I Andantino – Allegretto

2. II Scherzo: Vivace

3. III Intermezzo: Allegro moderato

4. IV Allegro tempestoso

Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, Op.26

5. I Andante – Allegro

6. II Temo con variazioni

7. III Allegro, ma non troppo

Sonata No.7 in B-flat major, Op.83

8. I Allegro inquieto

9. II Andante caloroso

10. III Precipitato

Stewart Goodyear, piano

BBC Symphony Orchestra

Andrew Litton, conductor

This is my first recording after my mother passed away in June of 2023. She has been with me for every step of my journey as a person, musician and recording artist, and the fact that she is no longer here is a very painful reality to face. Facing it every day when I practice, compose and even wake up is the new chapter of my life, and I see myself desperately wanting to believe that there is a spirit or ghost of her guiding me.

The seeds to this recording were sown 4 years ago…I wanted to record Prokofiev since the COVID pandemic. That period of uncertainty and quarantine was challenging, and I found myself leaning towards composers who have expanded the possibilities of a pianist’s endurance. Liszt’s B-minor sonata finally entered my fingers as learning that work became an obsession. I also went back to a composer I used to play when I first began taking the plunge to the performance circuit: Sergei Prokofiev.

Prokofiev always felt like a young pianist’s favourite to me, filled with vitality, speed, volume and aerobics. Protocol and restraint are thrown to the wind, and one feels like a rock god after playing this guy’s music. I haven’t played Prokofiev in 20 years and playing him again after so long thankfully brought the same memories and energy as when I decided to record, at age 40, my own Piano Sonata which I wrote when I was 18 years old. Deciding to record Prokofiev at age 45 was my new project.

The second concerto is described as one of the most demanding works in the concerto literature for piano, rivalling Rachmaninoff’s 3rd. The cadenza in both concertos in the first movement either scares pianists away or attracts them because of the difficulties presented. The other movements are no less demanding, and it is the pianist’s decision to either take the demands or leave them. There is no middle ground, and again, it attracts the hunger, endurance and unconquerable spirit of youth. It is dark, menacing and explosive, but also humorously macabre and soulful.

The third concerto is one of the most popular piano concertos ever written…. It is fun and filled with humor and biting parody, but also deeply touching with soaring lyricism. It is the perfect vehicle for competitions, and debuts in prestigious orchestras and venues. Pianists and audiences alike build up a sweat until the exciting ending which brings the house down every time. The spirit of youth is in this work too, the rock god showing his/her might, agility, wildness, tenderness and strength.

The seventh sonata was a work I included on many of my recital programs in my early 20s and is still one of my very favourite pieces of music. The rhythmic drive, dissonance, harmonic uncertainty and motor-like intensity brought on a whole new meaning by the time I finally recorded the work. More on that later….

I first worked with Andrew Litton in Philadelphia, and he was conductor for my first Rach 3 performance with the Bournemouth Symphony. We also performed Gershwin’s Concerto in F together in Glasgow. Every time I work with Andrew, he brings out the spirit of youth in me, and the excitement that he exudes to myself, and the orchestra is ageless, tireless and fearless. He allows me to bring my wildness to the table and pushes me to go further. I was delighted when he said yes to my invitation to be my collaborator on my Prokofiev disc.

Ditto my dear producer and dream guru Andrew Keener and engineer extraordinaire Dave Rowell! They were encouraging spirits on my journey recording Beethoven’s Piano Concertos and my own Callaloo Suite. This is my third collaboration with both beautiful human beings and maestros of their craft.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra is one of the greatest orchestras in the world, and it was a delight to finally work with this ensemble for this recording. The first time I heard the BBCSO perform was when I was 13 years old, and they performed a concert version of Prokofiev’s opera, “The Fiery Angel”. That concert left such a visceral impression on me, and hearing such intensity and wildness at the Royal Albert Hall was an experience I will always treasure.

There is a well-known proverb: “We plan, God laughs.” The team, the dates and the recording venue at the BBC Maida Vale Studios were set in motion…and then the inexplicable happened the month before our session. My right arm and wrist went out of whack. There was immense pain in my shoulders, and I felt like my fingers lost their strength: A pianist’s worst nightmare. I was practicing slower than I have ever done, feeling like I was going back to level 1 and learning how to play again. It was the scariest feeling. I scheduled acupuncture, exercised my arms and fingers, and prayed like I never prayed before. Finally, I bought a machine with muscle stimulators. The combination of all these made things improve, but not completely, and thoughts of cancelling the recording session entered my mind.

It was a miserable December 2023…With the fear of cancelling my recording session, my arm and fingers not working, and spending Christmas without my mother, I was in an emotional slump. What kept me going was practicing Prokofiev no matter what, pushing myself to reach the highest level of discipline possible. Morning, noon and night, I was in Prokofiev mode, my arm sore, my fingers weak, and my mind raw with emotion. I found the spirit of my mother guiding, pushing and encouraging me. I was also reminding myself that this is a project that I could not cancel…. The recording sessions were two weeks away, and I could not let anybody involved in the project down, including myself.

A few days before the recording sessions, I emailed Chi-chi Nwanoku, the founder of Chineke! and one of my dearest supporters and friends and asked whether it was at all possible for me to stay at her place for the days of my recording session. I was so grateful she said yes…. She was in Australia and allowed me to stay at her London home in her absence.

The first day of recording began, and a miracle happened: I got the strength of my arm back, and my fingers were strong again. From the first note, I felt like I could play again, and relief covered me like a warm blanket. The trials of December, emotionally and physically, became the ultimate preparation. It was as if I had to go through that baptism of fire to get a deeper understanding of each of the pieces I was going to record. The anguish and the pain, the defiance and the anger, and finally the joy, humour and the hard-earned victory. Prokofiev became to me not merely a composer of youthful exuberance, but one of ultimate endurance: the endurance to keep going no matter the obstacles.

My deepest thanks to everyone who was part of this journey…Thank you to Prokofiev himself, Chi-chi, Matthew Trusler of Orchid Classics, Andrew Litton and Andrew Keener, Dave Rowell, and all the members and staff of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. To my mother…This album is dedicated to you. I miss you, thank you, and love you.

Stewart Goodyear, 2024

‘I was never particularly close with Prokofiev the man,’ Sviatoslav Richter recalled. ‘For me he was all in his works… Acquaintances with his compositions were acquaintances with Prokofiev himself.’ This certainly chimes with Stewart Goodyear’s own thoughts on this album, in which he recalls the draw of Prokofiev’s music for young pianists in search of a challenge and the vivid characterisation of the pianist-composer’s works for his own instrument.

The Second Piano Concerto as we now hear it is not quite as Prokofiev first composed it between 1912 and 1913. It was written hard on the heels of his First Concerto; but the orchestral score of the Second was destroyed during the Russian Revolution, when looters raided his apartment. Prokofiev reconstructed the full work from a piano score that his mother had rescued, and this new version was premiered in 1924.

The opening Andantino recalls Rachmaninoff, lyrical and richly impassioned yet harmonically unstable and uneasy. From this a jaunty wind-dominated Allegretto emerges, all angles and virtuosic gestures from the soloist. The culminating cadenza is, as Goodyear observes, absolutely fearsome: so much so that even when played exactly, the effect is almost of the pianist losing his grip and only gradually regaining it as Prokofiev provides fistfuls of ever more unexpected chords. The Scherzo is a wild perpetuum mobile, full of scampering passagework and bulging dynamics; whilst the Intermezzo is grotesque, a times witty and at times positively frightening. A furious finale completes the picture.

No wonder critics were entirely divided – the progressives impressed, the conservatives outraged – which was just as Prokofiev, clearly out to shock, had hoped for. But this was not simply the act of a young composer determined to cause trouble. The Concerto was dedicated to the pianist Max Schmidthof, a dear friend of the composer, who had killed himself in 1913. Prokofiev’s admirer Boris Asafyev later identified the Concerto as a much darker work than it might appear at first hearing: ‘not so much brilliant as emotionally condensed, ‘compressed’ to the point of suffocation.’

In the spring of 1918, Prokofiev left Russia for America. Although he professed himself a supporter of the Revolution, he clearly realised the catastrophic impact that such political instability – not to mention the possibility of civil war – would have on Russian cultural life, and decided to try his luck elsewhere. By this this time he had already begun his Third Piano Concerto, which was completed in 1921. Prokofiev premiered it in December of that year with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conductor Frederick Stock, an energetic advocate of Prokofiev’s music in the USA.

This C major Concerto uses several ‘white’ themes – which is to say, themes which only use the white keys of the piano. A gently lyrical introduction takes us into an Allegro bursting with energy and power; although its second theme is, surprisingly, a kind of gavotte (a Baroque dance form) with castanet accompaniment. A theme and variation set follows, Prokofiev providing us with another gavotte, perky and graceful, as his theme. The finale opens with another ‘white’ theme, but it takes a long time to reach any kind of resolution. Expansive orchestral gestures are met with some curiously detached responses from the piano, and it is only in the last few minutes of the piece that we reach to C major, Prokofiev nailing the music firmly back into place with a series of repeated home chords.

Two decades separate these concertos from Prokofiev’s Seventh Sonata, completed in 1942. By now he had returned to the Soviet Union, and in 1939 he began three sonatas almost simultaneously, sketching out themes and certain key passages, and then returning to them over the next few years to flesh them out. These ‘war sonatas’ are the Sixth (1940), Seventh (1942) and Eighth (1944).

This time it was not the composer himself who gave the premiere, but the 28-year-old Sviatoslav Richter, playing it in Moscow in January 1943. ‘It was intensely fascinating, and I learned it in four days,’ Richter recalled. ‘Disorder and uncertainty reign. Man observes the raging of death-dealing forces, but what he lived for doesn’t cease to exist. He feels, he loves. The fullness of what he is feeling reaches out toward others. He is together with the rest of mankind, protesting and suffering deeply with them in their common grief. Full of a will for victory, he makes a headlong running attack, clearing away all obstacles. He will become strong through struggle, expanding into a gigantic and life-affirming force.’

© Katy Hamilton

Canadian pianist Stewart Goodyear, in a seminal year approaching his debut at the BBC proms, presents his new album of works by Sergei Prokofiev, alongside the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Andrew Litton.

Proclaimed “a phenomenon” by the Los Angeles Times and “one of the best pianists of his generation” by the Philadelphia Inquirer, Stewart Goodyear has carved out a formidable international reputation as both concert pianist and composer, with an impressive catalogue of recorded repertoire to date. Following on from his releases of Beethoven, Ravel, Gershwin and his own suite for piano and orchestra, “Callaloo” along with his piano sonata, Goodyear’s new recording features some of the greatest works in the repertory: the Op. 16 and Op. 26 Piano Concertos, as well as the Piano Sonata no. 7 in B flat major.

This ambitious undertaking, with its roots in the struggles of the 2020 pandemic, is inherently personal to Goodyear, as he revisits one of the key composers from his very first days on the piano recital circuit, and channels the youthful dynamism and vibrancy central to Prokofiev’s music. With Goodyear’s sage and seasoned take on these three works, the album takes on another dimension: that of steadfast endurance in the face of personal challenges.

Stewart Goodyear

Piano

Proclaimed “a phenomenon” by the Los Angeles Times and “one of the best pianists of his generation” by the Philadelphia Inquirer, Stewart Goodyear is an accomplished concert pianist, improviser and composer. Mr. Goodyear has performed with, and has been commissioned by, many of the major orchestras and chamber music organizations around the world.

Last year, Orchid Classics released Mr. Goodyear’s recording of his suite for piano and orchestra, “Callaloo” and his piano sonata. His recent commissions include a Piano Quintet for the Penderecki String Quartet, a piano work for the Honens Piano Competition, and a piano trio for the Horszowski Trio. His composition for solo cello and piano, “The Kapok” was recorded by Inbal Negev and Mr. Goodyear, and his suite for solo violin, “Solo”, was commissioned and recorded by Miranda Cuckson. Mr. Goodyear’s new work, “Life, Life, Life”, commissioned by the Chineke! Orchestra was performed by the same forces at the Southbank Centre May 2024.

Mr. Goodyear’s discography includes the complete sonatas and piano concertos of Beethoven, as well as concertos by Tchaikovsky, Grieg and Rachmaninov, an album of Ravel piano works, and an album, entitled “For Glenn Gould”, which combines repertoire from Mr. Gould’s US and Montreal debuts. His Rachmaninov recording received a Juno nomination for Best Classical Album for Soloist and Large Ensemble Accompaniment. Mr. Goodyear’s recording of his own transcription of Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker (Complete Ballet)”, was chosen by the New York Times as one of the best classical music recordings of 2015.

Recent appearances have included his Carnegie Hall debut with the Royal Conservatory Orchestra of Toronto May 2024, his performance of his “Callaloo” Suite with the Chineke! Orchestra under conductor Andrew Grams at the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, his return to the Ladies Morning Musical Club in Montreal, Canada, and performances with the Milwaukee and Nashville Symphony orchestras, the Buffalo Philharmonic, and his debut with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and the Korean National Symphony Orchestra.

Highlights for the 2024-25 season are his performances at the BBC Proms with the Chineke! Orchestra, performances at the Rheingau Musik Festival, and performances with the Indianapolis, Vancouver and Toronto Symphonies, the Rochester Philharmonic, Frankfurt Museumorchester, and A Far Cry in Boston.

Andrew Litton

Conductor

Andrew Litton, Music Director of New York City Ballet since 2015, is also the former Principal Guest Conductor of the Singapore Symphony, Conductor Laureate of Britain’s Bournemouth Symphony and Music Director Laureate of Norway’s Bergen Philharmonic. Under Litton’s leadership the Bergen Philharmonic gained international recognition through extensive recording and touring. Norway’s King Harald V knighted Litton with the Norwegian Royal Order of Merit. Other honours include Yale’s Sanford Medal, the Elgar Society Medal, and an honorary Doctorate from the University of Bournemouth.

Litton was Principal Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony from 1988–1994 and Music Director of the Dallas Symphony from 1994–2006. During his twelve years in Dallas, he led the orchestra on three major European tours, and appeared four times at Carnegie Hall. Andrew’s discography boasts over 135 recordings.

Recent and forthcoming highlights include his debut with the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden and performances with a range of international orchestras, including the Singapore Symphony, Bergen Philharmonic, BBC Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Seattle Symphony, Orquesta Sinfonica de Galicia, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony and cycles of the piano concertos and symphonies of Rachmaninov with the Adelaide Symphony.

An avid opera conductor with a keen theatrical sense, Litton has led major opera companies such as the Metropolitan Opera, The Royal Opera Covent Garden, Opera Australia and Deutsche Oper Berlin. In Norway, he was key to founding the Bergen National Opera, where he led numerous acclaimed performances.

An accomplished pianist, Litton performs as a soloist, conducting from the keyboard. He is also an acknowledged expert on and performer of Gershwin’s music and serves as Advisor to the University of Michigan Gershwin Archives.

BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra has been at the heart of British musical life since it was founded in 1930. It plays a central role in the BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall, performing at the First and Last Night each year in addition to regular appearances throughout the Proms season with the world’s leading conductors and soloists.

The BBC SO performs an annual season of concerts at the Barbican in London, where it is Associate Orchestra. Its commitment to contemporary music is demonstrated by a range of premieres each season, as well as Total Immersion days devoted to specific composers or themes, and its richly varied programming includes well-loved works at the heart of classical music, newly commissioned music, collaborations with highly regarded musicians from the world of pop and, in recent years, evenings of words and music featuring readings by well-known authors.

The BBC SO has close relationships with its world-class roster of conductors and guest artists: Chief Conductor Sakari Oramo, Principal Guest Conductor Dalia Stasevksa, holder of the Günter Wand Conducting Chair Semyon Bychkov and Creative Artist in Association Jules Buckley. It also makes regular appearances with the BBC Symphony Chorus.

The vast majority of performances are broadcast on BBC Radio 3 and a number of studio recordings each season are free to attend. These often feature up-and-coming new talent, including members of BBC Radio 3’s New Generation Artists scheme. All broadcasts are available for 30 days on BBC Sounds and the BBC SO can also be seen on BBC TV and BBC iPlayer and heard on the BBC’s online archive, Experience Classical.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus – alongside the BBC Concert Orchestra, BBC Singers and BBC Proms – also offer enjoyable and innovative education and community activities and take a leading role in the BBC Ten Pieces and BBC Young Composer programmes.

bbc.co.uk/symphonyorchestra

Click the button above to download all album assets.